Pages That Mention Columbia River

Coast Guard District narrative histories 1945

33

Lightships are actually floating lighthouses placed on station in locations along the coast where it would be impracticable or needlessly expensive to build a lighthouse. Quite frequently, they mark the approach to a port or the outer limits of outlying dangers. The forerunner of the modern lightship was the beacon boat which was originated in 1789. It was a small boat with colored daymarks on the mast and was used for about 31 years. There was no sound or light equipment on the beacon boat and consequently, it was superseded by the light and bell boats in the early part of the 19th Century. These light and bell boats were queer structures made of iron, flash-decked, turtlebacked and with a light or bell clappers fastened to the mast. Later daymarks were added. Light boats, or floating lights, as they were then called, were mostly anchored in inside waters and it was not until the development of the sturdier lightship that hazardous locations along the open coast were able to be marked.

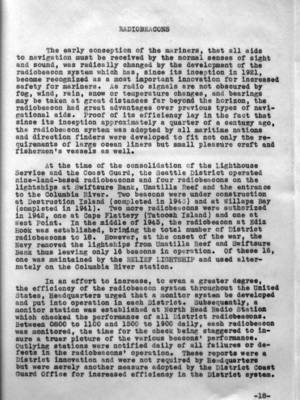

The first light vessel (the No. 50) to be placed on Pacific Coast was stationed at the entrance of the Columbia River in 1892 and was propelled by sails. At one time during her history, she parted her moorings in a tremendous sea and heavy gale and was stranded on the shore near the mouth of the Columbia River. She lay there

(Image bottom left)

LIGHTSHIP #50 WAS THE FIRST OF ITS KIND ON THE WEST COAST. THE CIRCULAR SCREENS ON THE MASTS WERE DAYMARKS AS NO LIGHTS WERE EXHIBITED DURING THE DAY. AT NIGHT, 3 OIL LANTERNS WERE RUN UP EACH AUXILIARY MAST (AFT OF THE MASTS BEARING DAYMARKS.

34

for 16 months before it was decided that the only possible means of returning her to her station was by hauling her overland through the woods and launching her in the Columbia River. The No. 50 was constructed of wood and remained in service only until 1909 when she was replaced by the steel-hulled lightship.

During the amalgamation of the Lighthouse Service and The Coast Guard in 1939, four lightships, the COLUMBIA RIVER LIGHTSHIP 393, the UMATILLA REEF LIGHTSHIP #88, the RELIEF LIGHTSHIP #92 and the SWIFTSURE LIGHTSHIP #113, were transferred to the Coast Guard. These four lightships maintained only three stations as the RELIEF LIGHTSHIP #92 was used on all stations as relief. They were steel-hulled vessels with a displacement of approximately 685 tones and a complement of 3 to 6 officers and 5 to 11 crew. All but one was built around 1908; the SWIFTSURE LIGHTSHIP #113 was the newest and it was completed in 1929. In addition to exhibiting a bright beacon light, the lightships were also equipped with sound signals, [radio]], radio-telephone, and radiobeacons. In addition to their regular duties as lightships, they were also instructed during the early days of the war, to notify the Commandant, 13th Naval District of all vessels passing the Columbia River northbound.

At the outbreak of the war, LIGHTSHIPS NO. 88 and 113, were removed from their stations by the Navy and replaced by lighted whistle buoys. The ships were reconverted by removing the radiobeacon and antenna mast, by installing armament, by realtering radio facilities and by increasing the complement to 30 Coast Guardsmen and 5 Coast Guard Officers. The No. 88 was then placed in the Strait of Juan de Fuca as a Recognition Ship and the No 113 was sent into Alaskan waters. The removal of these two ships left only the COLUMBIA RIVER LIGHTSHIP #93 on station at the entrance to the Columbia River with the No. 92 to be used as its relief.

The use of one lightship as standby only, seemed most uneconomical of ships and men at a time when they were at a premium. The District Coast Guard Officer, with the approval of the Commander, Northwest Sea Frontier, proposed to Headquarters that the COLUMBIA RIVER LIGHTSHIP #93 should remain on station for a month and then, on a clear day with good weather, the ship would leave her station, go to Astoria for fuel and supplies and return before dark. A station buoy would be placed close to the Lightship's position at all times and mark the station when the Lightship itself was absent. Such an arrangement would permit the RELIEF LIGHTSHIP to be used as part of the Offshore Observation Force.

37

The early conception of the mariners, that all aids to navigation must be received by the normal senses of sight and sound, was radically changed by the development of the radiobeacon system which has, since its inception in 1921, become recognized as a most important innovation for increased safety for mariners. As radio signals are not obscured by fog, wind, rain, snow or temperature changes, and bearings may be taken at great distances far beyond the horizon, the radiobeacon had great advantages over previous types of navigational aids. Proof of its efficiency lay in the fact that since its inception approximately a quarter of a century ago, the radiobeacon system was adopted by all maritime nations and direction finders were developed to fit not only the requirements of large ocean liners, but small pleasure craft and fisherman's vessels as well.

At the time of the consolidation of the Lighthouse Service and the Coast Guard, the Seattle District operated nine-land-based radiobeacons and four radiobeacons on the lightships at Swiftsure Bank, Umatilla Reef and the entrance to the Columbia River. Two beacons were under construction at Destruction Island (completed in 1943) and at Willapa Bay (completed in 1941). Two more radiobeacons were authorized in 1842, one at Cape Flattery (Tatoosh Island) and one at West Point. In the middle of 1945, the radiobeacon at Ediz Hook was established, bringing the total number of District radiobeacons to 18. However, at the onset of the war, the Navy removed the lightships from Umatilla Reef and Swiftsure Bank thus leaving only 16 beacons in operation. Of these 16, one was maintained by the RELIEF LIGHTSHIP and used alternately on the Columbia River station.

In an effort to increase, to even a greater degree, the efficiency of the radiobeacon system throughout the United States, headquarters urged that a monitor system be developed and put into operation in each District. Subsequently, a monitor station was established at North head Radio Station which checked the performance of all District radiobeacons. Between 0800 to 1100 and 1500 to 1900 daily, each radiobeacon was monitored, the time for the check being staggered to insure a truer picture of the various beacons' performance. Outlying stations were notified daily of all failures or defects in the radiobeacons' operation. These reports were a District innovation and were not required by Headquarters but were merely another measure adopted by the District Coast Guard Office for increased efficiency in the District system.

-18-

38

An arrangement was made for rating the radiobeacons on a percentage basis for efficiency of operation. For each various type of failure, an established number of points were deducted from a perfect score. These scores were then arranged in chronological order and published each month. However, a discrepancy was evident in that one station operating on the wrong minute for 35 minutes received the same percentage rating as a station being off sequence for only 10 minutes. A new plan for such rating was established and put into operation in the early part of 1945. This new system was so arranged that an offending radiobeacon station was marked down for not only the type of failure, but for the number of minutes of faulty operation. This accounted for the low percentage rating for 1945 of 94% as compared with the percentage rating of 96% for 1943 and 98% for 1944. Actually, the number of failures occurring after the February survey (see survey below) in 1945 became less than those in the months prior to that date.

The Radiobeacon Station guilty of the most failures was on the Columbia River Station. The high percentage of failures in this case was due to a combination of old equipment, fluctuating voltage, disinterested personnel, too small a complement and the motion of the ship, which tended to dislodge the sensitive parts, especially during heavy seas. Little or no interference was found in any of the radiobeacons. One instance of expeditious conduct occurred at Yaquina Head Radiobeacon Station when lightning struck the building in which the beacon was housed and destroyed the equipment and severely injured the operator on watch. Only twelve (12) minutes elapsed between the time the radiobeacon was struck and put out of commission before the standby unit was operating normally.

Peace time operation of the radiobeacon consisted of the distance finding dash being sounded when fog was actually in the area of the radiobeacon and the fog signal was in operation. During the war, the distance finding dash was used continuously as for fog for the purpose of not allowing the enemy to know whether it was foggy or clear weather. Two days after the declaration of war, on 9 December, 1941, the radiobeacon stations were instructed that no radiobeacon signals and no test transmissions in the radiobeacon band were to be permitted during the emergency without specific authorization from the District Coast Guard Officer. This order permitted no variation and forbade all radio frequencies radiation within the band from 285 to 315 kcs. from any radiobeacon stations. Radiobeacon transmitters on any frequency

42

Causes of radiobeacon failures were generally easily repairs, but it was the duration of these failures which the District Coast Guard Office worked incessantly to overcome. Monitor stations experienced great difficulty, at times, in notifying an offending station of its inoperation due to the frequent inability to make radio contact with the radiobeacon station which necessitated routing the message through other stations or agencies. Heavy storms in the area destroyed telephone communication and on occasion, visual signals had to be relayed to certain stations. Alarm units, as noted above, were not perfected, so frequently radiobeacon stations were unaware of their defective operation until notified by the Monitor Station. Had there been some means for notifying, under all conditions, the radiobeacon station of its faulty operation immediately after the failure was detected, the duration of faulty operation would have been greatly reduced.

Although the radiobeacons in this District were not operating at 100% efficiency, it was the opinion of the District Office that the beacons were operating on a par with beacons throughout the continental United States. This was determined by the reports from mariners and airmen who used beacons as navigational aids and was also due to the determination of the Aids to Navigation Officer to increase the efficiency of the beacons.

A radiobeacon buoy with a working range from 7 to 50 miles had been developed and was considered in the 13th Naval District the year before the war. Trials were made on batteries in some of the rough waters along the coast and on the Columbia River Bar. The batteries proved too fragile so dry packs were tested; these, too, developed defects. As the packs cost $40.00 a piece, much experimentation proved too costly. The District Coast Guard Officer saw the advantage of a perfected radiobeacon buoy in that a string of such buoys along the coast, 15 to 20 miles apart on the 30 fathom curve, would eliminate the necessity of the UMATILLA REEF LIGHTSHIP; the removal of the Lightship would counteract the use of tenders servicing the equipment (buoys had to be serviced every 4 months), as well as the cost. The Aids to Navigation Officer and the District Coast Guard Officer were both in favor of the establishment of a radiobeacon buoy at Grays Harbor Entrance where there had been considerable agitation for a Lightship; this station was within easy run for the CGC MANZANITA. Had the buoy proved applicable to conditions at Grays Harbor, buoys could have easily been installed at Duntze Rock, Yaquina Bay, Tillamook Rock, Umpqua, Coos Bay and Wherever tender equipment was available.

-23-