Pages

6

πλ 6

algabraic diagram presents to our observation the very identical object of mathematical research, that is, the form of the harmonic mean, which this equation aids one to study. Not only is it true that by experimentation upon some diagram an experimental, or inductive, proof can be obtained of every necessary conclusion from a given premiss [I speak of premiss, in the singular, because two or more premisses can be reduced to a single correlative premiss, as is in fact done in my usual manipulation of logical algebra and other logical diagrams,] but what is more, no "necessary" conclusion is any more apodictic than inductive reasoning becomes, as soon as experiments may be multiplied, ad libitum, of no more cost than that of imagining a new diagram, and experimenting upon it in the imagination. I might give a perfect

7

πλ 7

proof of this, and am only dissuaded from doing so now and here, no such proof having yet been published, by the exigency of space, the inelectuable length of the requisite explanations, and the disposition of logicians to accept the conclusion on the strength of J.A. Lange's persuasive, albeit defective and in points even erroneous apology for it. Under the circumstances, I will content myself with a general sketch of my proof. First, an analysis of the essence of a sign (taking that word in the most general sense, as anything which being determined by an object, determines an interpretant to determination through it by the same object) leads to a proof that every sign is determined by its object either, 1st, by partaking in the characters of that object (as a diagram is), or 2nd, by being actually determined by that object, regardless of any representation that it is so, or 3rd, by being connected with that object for given interpretants, that is, by being

8

πλ 8

mentally associated with the object. In this statement, however, perfect accuracy is sacrificed to perspicuity. To these three kinds of signs I give the names, icon, index, and symbol, respectively. (The division was published in 1867.) I next show that no study, experiment, or other operation upon a symbol of an object can lead to anything more than a different form of thought about that object; and that no operation upon an index of an object, though it may yield new truth about the object, can ever furnish apodictic proof of that truth. The study of an icon, on the contrary, though its results can no more be infallible than is the summation of a column of figures, may disclose necessary, i.e. essential, truths regarding the object. I never consider what can be effected by the connected study of different signs, and thus find that while

9

πλ 9

symbols and indices are indispensible in reasoning, yet it is icons only that rationally determine any true representation of the object. But at last we have to face the burly objector who does not see that any signs at all are needed in reasoning. It is true that the complete premiss of a necessary argument is, ipso facto, a sign of the truth of the conclusion; but that does not prove that signs are requisite to the eduction of the conclusion from the premiss. This is an objection too broad to be blinked or to be summarily passed over. This was the inner spring of the Gereral's objection, and it recurs again and again in the study of pragmatism. The answer, in brief, is that thoughts, and thinkings too, are signs. That thoughts refer to objects, whether these objects are fabrications of the thoughts or are independent beings, is evident. But this is not

10

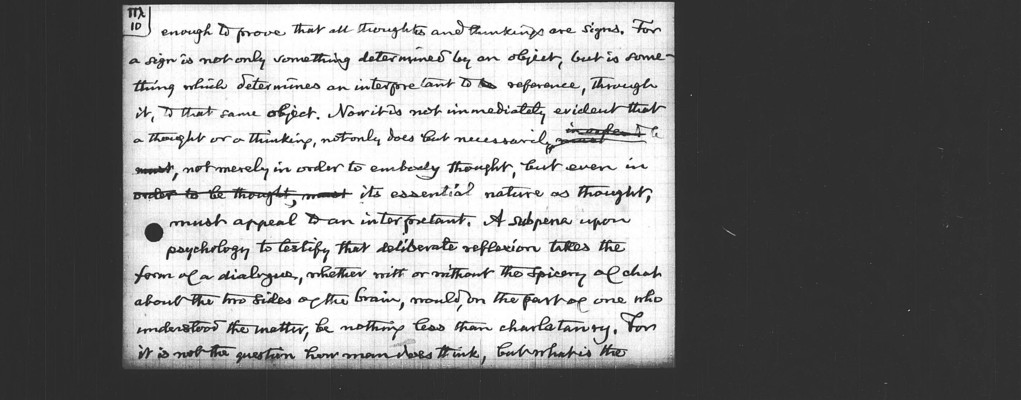

πλ 10

enough to prove that all thoughts and thinkings are signs. For a sign is not only something determined by an object, but is something which determines an interpretant to reference, through it, to that same object. Now it is not immediately evident that a thought or a thinking, not only does but necessarily must, not merely in order to embody thought, but even in its essential nature as thought, must appeal to an interpretant. A subpena upon psychology to testify that deliberate reflexion takes the form of a dialogue, whether with or without the spicery of chat about the two sides of the brain, would, on the part of one who understood the matter, be nothing less than charlatanry. For it is not the question how man does think, but what is the