Pages

21

Logic II 21

would reject all weights outside a certain "tolerance", as it is called in coinage. Those that were too light would have to be thrown away. They would lie in a heap, until they appeared to deceive a future archaeologist. (Petrie's weights however, are somewhat heavier, not lighter, than independent evidence would lead us to believe the ket to have been.) Those that were too heavy would be reground, but would for the most part still be rather heavier than the standard. The consequence would be that the curve would be cut down vertically at two ordinates (equally distant, perhaps, from the standard,) while the ordinates of its maximum would be at the right of that of the standard. If the workman had a balance at hand, and frequently used it during the process of adjustment, the form of the error curve would depend upon the construction of the balance. If it were like a modern balance which shows so as to show not only that one mass is greater than another, but also whether it is much or little greater, the workman would put keep in one pan

22

Logic II 22

a weight equal to of the maximum value that he proposed to himself as permissible for the weight he was making; and in all his successive grindings would be aiming at that. The consequence would be a curve [diagram] concave upwards and stopping abruptly at its maximum ordinate; -- a form easily manageable by a slight modification of the method of least squares. [I have drawn the curve in the upper left hand corder of the plate.] But most of the balances shown upon the Egyptian monuments are provided with stops or other contrivances which would be needless if the balances were not top-heavy. * Now a top-heavy balance will not show that two weights are equal, otherwise than by remaining with either end down which may be down. It only shows when, a new a weight is put in dec being already in one pan, a decidedly heavier weight is placed in the other. The workman using such a balance would have no warning that he was approaching the limit, and would be unable to aim at

* Such balances, working automatically, are in [main?] all the mints of the civilized world, for throwing out light and heavy coins.

23

Logic II 23

any definite value, but (being, as we are supposing, devoid of skill,) would have to grind away blindly, trying his weight every time he had ground off about as much as the whole range of variation which he proposed to allow himself. If he always ground off precisely the same amounts between successive tryings of his weight, he would be just as likely to grind below his maximum by any one fraction of the amount taken off at a grinding as by any other; so that his error curve woud be a horizontal line cut off by vertical ordinates; thus [diagram]. But since there would be a variability in the amount taken off between the trials, the left hand side of the curve would show a sorted [moulding?] with a contracy flexure, this: [diagram]. [marginal insertion:] It must be admitted that the distribution of Petrie's kets is suggestive of this sort of curve, or rather or a modification of it due to a middling degree of skill.

Final Causation

I hope that long digression, (which will be referred to with some interest when we come to study the theory of errors) will not have caused the reader to forget that we were engaged in tracing out some of the consequences of understanding the term "natural" or "real" class to mean a class the existence of whose members is due to a common and peculiar final cause. It is, as I was saying, a wide-spread error to think that a "final cause" is necessarily a purpose. A purpose is

24

Logic II 24

merely that form of final cause which is most familiar to our experience. The signification of the phrase "final cause" must be determined by the its use in the statement of Aristotle that all causation divides into two grand branches, the efficient, or forceful; and the ideal, or final. If we are to conserve the truth of that statement, one must understand by final causation that mode of bringing facts about according to which a general description of any compulsion for it to appear come about in this or that particular way; although the means may be adapted to the end. The general result may be brought about at one time in one way, and at another time in another way. Final causation does not determine in what particular way it is to be brought about, but only that the general result shall have a certain general character. Efficient causation, on the other hand, is a compulsion determined by the particular

25

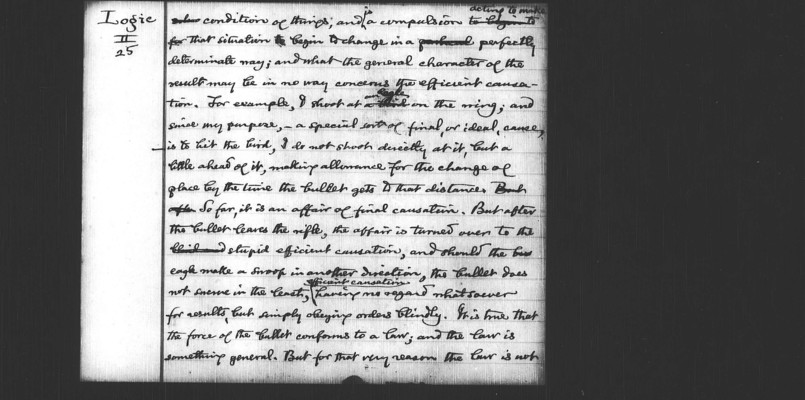

Logic II 25

[?] condition of things; and is a compusion to begin to acting to make for that situation to begin to change in a particular perfectly determinate way; and what the general character of the result may be in no way concerns the efficient causation. For example, I shoot at a bird an eagle on the wing; and since my purpose, -- a special sort of final, or ideal, cause, is to hit the bird, I do not shoot directly at it, but a little ahead of it, making allowance for the change of place by the time the bullet gets to that distance. But often So far, it is an affair of final causation. But after the bullet leaves the rifle, the affair is turned over to the blind and stupid efficient causation, and should the bird eagle make a swoop in another direction, the bullet does not swerve in the least, efficient causation having no regard whatsoever for results, but simple obeying orders blindly. It is true that the force of the bullet conforms to a law; and the law is something general. But for that very reason the law is not