Pages

41

Logic II 41

{Section title: Classification according to Final Causes.}

their boundaries differently drawn. After all, boundary lines may be [?] [?] in some cases can only be artificial, although the classes are natural, as we saw in the case of the kets. When one can lay one's finger upon the purpose to which a class of things owes its origin, then indeed abstract definition may formulate that purpose. But when one cannot do that, but one can trace the genesis of a class and see ascertain how several have been derived by different lines of descent from one less specialized form, this is the best way of getting route toward an understanding of what the natural classes are. This is true even in biology: it is much more clearly so when the objects generated are, like sciences, themselves of the nature of ideas.

{Section title: Classification by Ideas Types.}

There are cases where we are quite in the dark, alike concerning the creating purpose and the concering the genesis of things; but where we find a system of classes

42

Logic II 42

connected with a system of abstract ideas, -most frequently numbers, -- and that in such a manner as to give us [?] reason to guess that those ideas in some way, [?] usually obscure, [?] determine the possibilities of the things. For example, chemical compounds, generally, -- or, at least, the more decidedly characterized of them, including, it would seem, the so-called elements, -- seem to belong to types, so that, to take a simple example, chlorates KClO3, manganates KMn)3, bromates KBrO3, ruthemiates KRuO3, iodates KIO3, behave in chemically in strikingly analogous ways. That this sort of argument for the existence of natural classes, -- I mean the argument drawn from types, that is, from a connection of between the things and a system of abstract formal ideas, -- may be much stronger and more direct than one might expect to find it, it shown by the circumstance that ideas themselves, surely and are they

43

Logic II 43

{Marginal note: There are 7 pages of MS numbered 43a, 43b, ... 43g}

{Section title: Classification by Ruling Numbers}

not the easiest of all things to classify naturally, with certain assured assured truth?-- can be classified on no other grounds that this, except in a few exceptional cases. In the Even in those few cases, this method would seem to be the safest. For example, in pure mathematics, almost all the classification reposes on the relations of the forms classified to numbers or other multitudes. Thus, in topical geometry, figures are classified according to the whole numbers attached to their choresis, cyclosis, periphraxis, and apeiresis etc. As for the exceptions such as the classes of hessians, jacobians, invariants, vectors, etc. they all depend upon types, of a too, although upon types of a different kind. It is plain that it must be so; and all the natural classes of logic will be found to have the same character.

I have now said enough concerning classification

44

Logic II 43a.

{Section title: Classes determined by examples, not by definition.}

There are two remarks [which?] more about natural classification which, though they are commonplace enough, cannot decently be passed by without recognition. They have both just been virtually said, but they had better be more explicitly expressed and put in a light in which their bearing upon the practice of classification shall be plain. The descriptive definition of a natural class, according to what I have been saying, is not the essence of it. It is only an enumeration of its members. A description of a natural class must be founded upon samples of it or typical examples. Possibly a zoologist or a botanist may have so definite a conception of what a species is that a single type-specimen may enable him to say whether a form of which he finds a specimen belongs to the same species or not. But it will be much safer to have a large number of indi-

45

Logic II 43b

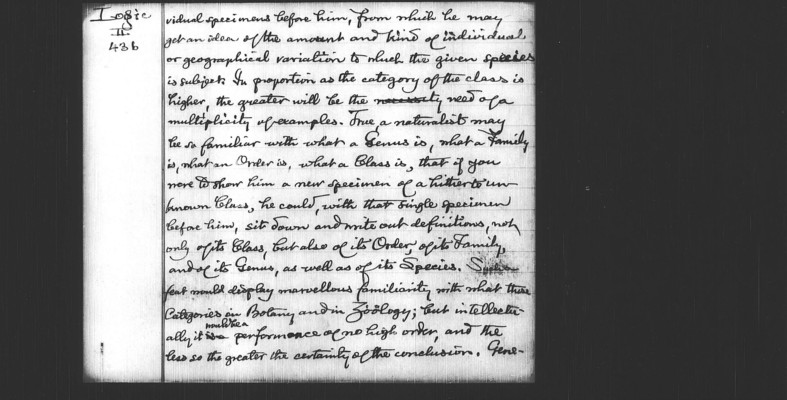

vidual specimens before him, from which he may get an idea of the amount and kind of individual or geographical variation to which the given species is subject. In proportion as the category of the class is highter, the greater will be the necessity need of a multiplicity of examples. True, a naturalist may be so familiar with what a Genus is, what a Family is, what an Order is, what a Class is, that if you move to show him a new specimen of a hitherto unknown Class, he could, with that single specimen before him, sit down and write out definitions, not only of its Class, but also of its Order, of its Family, and of its Genus, as well as of its Species. Such a feat would display marvellous familiarity with what those Categories in Botany and in Zoology; but intellectually it is a would be a performance of no high order, and the less so the greater the certainty of the conclusion. Gene-