Pages

1

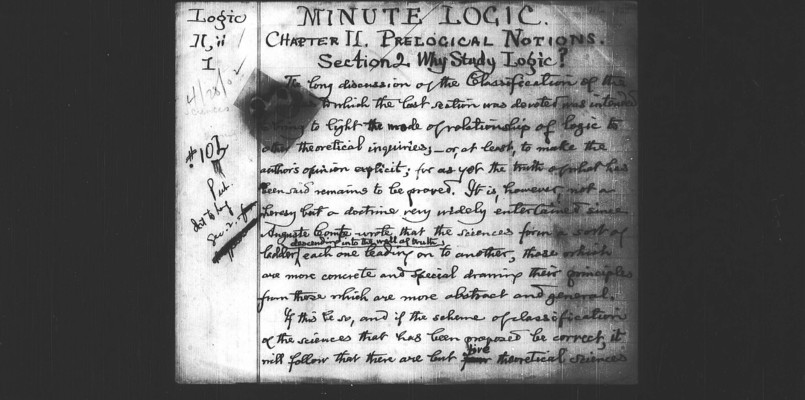

Minute Logic. Chapter II. Prelogical Notions. Section 2. Why Study Logic?

The long discussion of the Classification of the [sciences?] to which the last section was devoted was intended to bring to light the mode of relationship of logic to other theoretical inquiries; or, at least, to make the author's opinion explicit; for as yet the truth of what has been said remains to be proved. It is, however, not a heresy but a doctrine very widely entertained since Auguste Comte wrote that the sciences form a sort of ladder descending into the wall of truth, each one leading on to another, those which are more concrete and special drawing their principles from those which are more abstract and general.

If this be so, and if the scheme of classification of the sciences that has been proposed be correct, it will follow that there are but five theoretical sciences

2

Logic ][.ii 2

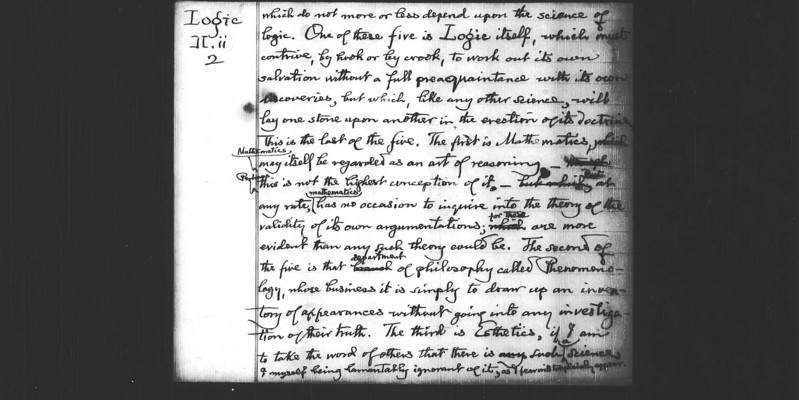

which do not more or less depend upon the science of logic. One of these five is Logic itself, which must contrive, by hook or by crook, to work out its own salvation without a full preacquaintance with its own discoveries, but which, like any other science, will lay one stone upon another in the erection of its doctrine. This is the last of the five. The first is Mathematics, which mathematics may itself be regarded as an art of reasoning_[?] Perhaps this is not the highest conception of it_[?] But at any rate, mathematics has no occasion to inquire into the theory of the validity of its own argumentations; for these are more evident than any such theory could be. The second of the five is that department of philosophy called Phenomono logy, whose business it is simply to draw up an inven tory of appearances without going into any investiga tion of their truth. The third is Esthetics, if I am to take the word of others that there is such a science, I myself being lamentably ignorant of it, as I fear will too plainly appear.

3

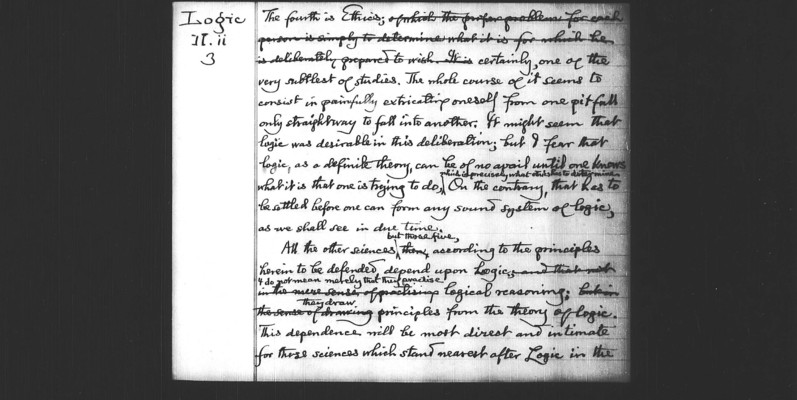

The fourth is Ethics, (of which the proper problem for each person is simply to determine what it is for which he is deliberately prepared to wish. It is) certainly, one of the very subtlest of studies. The whole course of it seems to consist in painfully extricating oneself from one pitfall only straightaway to fall into another. It might seem that logic was desirable in this deliberation; but I fear that logic, as a definite theory, can be of no avail until one knows what it is that one is trying to do, ^which is precisely what ethics has to determine. On the contrary, that has to be settled before one can form any sound system of logic, as we shall see in due time.

All the other sciences ^but those five, according to the principles herein to be defended, depend upon Logic. I do not mean merely that they practise logical reasoning; they draw principles from the theory of logic. This dependence will be most direct and intimate for those sciences which stand nearest after Logic in the

4

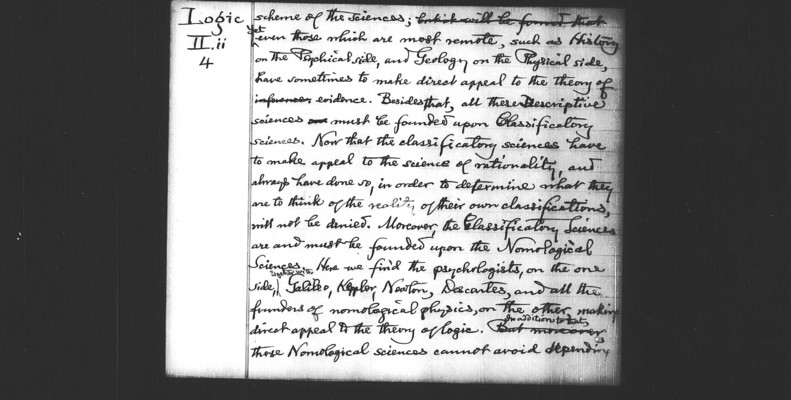

scheme of the sciences; [crossed out] yet even those which are most remote, such as History or the Psychical side, and Geology on the Physical side, have sometimes to make direct appeal to the theory of [crossed out] evidence. Besides that, all these descriptive sciences must be founded upon Classificatory sciences. Now that the classificatory sciences have to make appeal to the science of rationality, and always have done so, in order to determine what they are to think of the reality of their own classifications, will not be denied. Moreover, the Classificatory Sciences are are must be founded upon the Nomological Sciences. Here we find the psychologists, on the one side, together with Galileo, Keppler, Newton, Descartes, and all the founders of nomological physics, on the other, making direct appeal to the theory of logic. In addition to that, those Nomological sciences cannot avoid depending

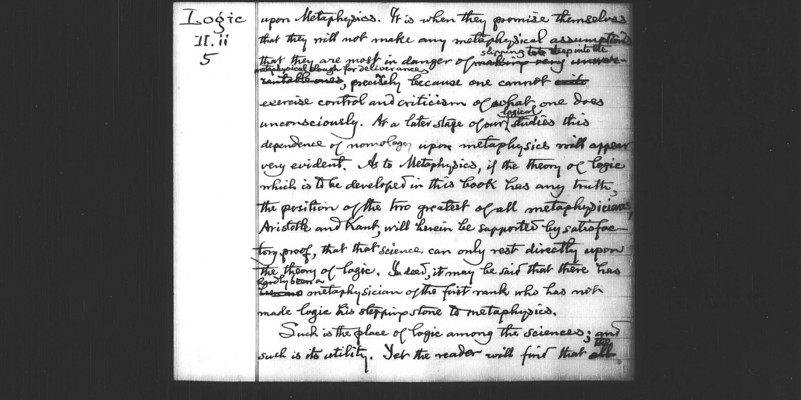

5

upon Metaphysics. It is when they promise themselves that they will not make any metaphysical assumptions that they are most in danger of slipping too deep into the metaphysical slough for deliverances, precisely because one cannot exercise control and criticism of what one does unconsciously. At a later stage of our logical studies this dependence of nomology upon metaphysics will apear very evident. As to Metaphysics, if the theory of logic which is to be developed in this book has any truth, the position of the two greatest of all metaphysicians, Aristotle and Kant, will herein be supported by saltisfac tory proof, that that science can only rest directly upon the theory of logic. Indeed, it may be said that there has hardly been a metaphysician of the first rank who has not made logic his stepping stone to metaphysics.

Such is the place of logic among the sciences; and such is its utility. Yet the reader will find that the