Pages

21

3rd. If it would be permissible to transform one graph, a, into another, b, it is permissible to scribe 4th. Whenever it is permissible to scribe

{{tex: \vscroll { \ a\ }{b} :tex}}

it is would be permissible were a scribed, to scribe b. 5th. A vacant enclosure may be called a blot is not permissively scriptible, and as such is [called a blot?] 6th. Any enclosure having a blot in its area may be cancelled or erased.

Here we have the three signs defined purely in terms of [what?] the logical transformations from them and to them without one word being said about what the signs really mean. They are left to be applied to whatever there may be that corresponds to them. This is the Pure Mathematical point of view, a point of view far from easy to a person as imbued with logical notions as I am.

These 6 rules are not quite so convenient, as are 3 rules, each double, which can without difficulty be proved to follow from these 6. These three double rules are what I call the three fundamental alpha rules of existential graphs.

They are as follows: I proceed to state them [Go to middle of p. 15] 1st, Rule of Erasure or Insertion 2nd, Rule of Iteration or Deiteration 3rd, Rule of Double Enclosure the Double Cut.

22

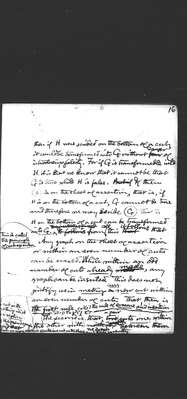

16

then if H were scribed on the bottom of a cut, it could be transformed into G without fear danger of introducing falsity. For if G is transformable into H, it is that we know that it cannot be that G is true while H is false. But if If then is on the sheet of assertion, that is, if H is on the bottom of a cut, G cannot be true and therefore we may scribe That is H on the bottom of a cut can be transformed into G. This is called the principle of contraposition. From all this it follows that

Any graph on the sheet of assertion or within an even number of cuts can be erased. While within an odd number of cuts already made, any graph can be inserted. This does not justify us in making any new cut within an even number of cuts. That, then is the first rule, called the rule of erasure and insertion.

[note here: Skip to p. 17]

The second is that a pair of cuts one within the other with no graph between them [????]

23

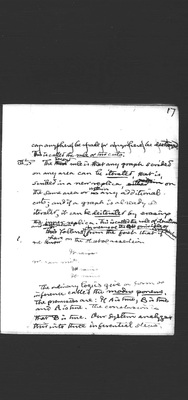

17

can anywhere be made or anywhere be destroyed. This is called the rule of two cuts. The third second rule is that any graph scribed on any area can be iterated, that is, scribed in a new replica, on the same area or within any additional cuts; and if a graph is already so iterated, it can be deiterated by erasing the inner replica. This is called the rule of iteration and deiteration. It follows by means of the principle of contraposition from the fact that if we have on the sheet of assertion

It rains

we can write

It rains It rains.

The ordinary logics give a form of inference called the modus ponens. The premisses are: If A is true, B is true and A is true. The conclusion is that B is true. Our system analyzes this into three inferential steps.

24

18

We have

a The rule of iteration and deiteration gives us a right to

a

The rule of two cuts gives a b

Finally, the rule of erasure and insertion gives b

I now pass to the beta part of the system of existential graphs. It is far more interesting and important than the alpha part but incomparably less so than the gamma part.

When one hears a proper name mentioned for the first time, one generally learns of the individual person or thing denoted by that name that it exists. It may, of course, be identified with a subject of force already well-known; but that will be exceptional. It will frequently be obvious apparent that it is a thing quite different from any hitherto

25

19

mutually recognized. In this case, it will make an addition to the universe of discourse, brought about by means of the assertion of a real relation of it to an object previously recognized. Sometimes, it will be doubtful whether it is one of the recognized subjects of force or not. Butwhat I want to focus your attention upon is, that at the first mention of a proper name, apart from any special information about its subject that may then be conveyed, the name merely tells us that something exists, that is, is a factor of the entire complexus of forces that we [partly?] have known by experience. But at any subsequent mention of the proper name, though this assertion of existence is reiterated, yet that being know[n?] already is of no importance. The importance of the name at all occurrences after the first is that it identifies what is mentioned with something we had heard of before.