Pages

31

24

We call such a heavy line a line of identity. A point from which three lines of identity proceed has the force of the conjunction ‘and.’

There is no need of a point from which four lines of identity proceed; for two triple points answer the same purpose.

Therefore a figure like this is to be understood as two distinct lines of identity crossing one another. Nevertheless, in order to avoid possible mistake a bridge may be represented thus: One line passes under the bridge, the other upon it.

The more you scribe on the bottom of a cut, the less you assert. Thus means: It is not true that somebody returns to earth nor is it true that somebody is translated. But

32

25

merely says that both are not true. That is one or [the] other is false. Either nobody returns to earth or else nobody is translated.

Add to this a line of identity joining the two and still less is asserted. Either nobody is translated or if anybody is translated, that person does not return to earth.

Now take this That means somebody is a prophet but nobody is translated. If we continue the outer line to the cut, it will make no difference for no significance attaches to the shape of the line. If, however, the

33

26

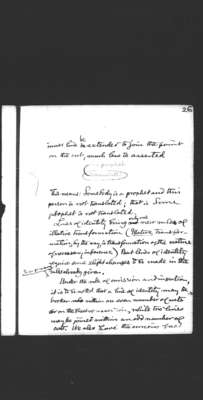

inner line be extended to join the point on the cut, much less is asserted

This means: Somebody is a prophet and this person is not translated; that is Some prophet is not translated.

Lines of identity bring no only one new rule of illative transformation. (Illative transformation, by the way, is transformation of the nature of necessary inference.) But lines of identity require some slight changes to be made in the three primary rules already given.

Under the rule of omission and insertion, it is to be noted that a line of identity may be broken within an even number of cuts or on the sheet of assertion, while two lines may be joined within an odd number of cuts. We also have the curious fact

34

27

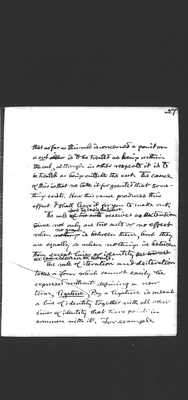

that as far as this rule is concerned a point on a cut is to be treated as being within the cut, although in other respects it is to be treated as being outside the cut. The cause of this is that we take it for granted that something exists. How this cause produces this effect I shall leave it for you to make out.

The rule of two cuts about the double enclosure receives an extension since not only are two cuts of no effect when nothing no graph is between them, but they are equally so when nothing is between them except lines of identity that [traverse?] the space between the two cuts.

The rule of iteration and deiteration takes a form which cannot easily be expressed without defining a new term, ligature. By a ligature is meant a line of identity together with all other lines of identity that have points in common with it. For example