Pages

82

84

does not stand in that relation, while there is nothing to which the second stands in that relation without the first standing in the same relation to it; or else it is just the other way, namely that the second stands in the relation, R, to which the first does not stand in that relation, while there is nothing to which the first stands in that relation, R, without the second also standing in the same relation to it. The proof of this, which is a little too intricate to be followed in an oral statement (although in another lecture I shall substantially prove it) depends upon the fact that a relation is in itself a mere logical possibility.

I will now pass to another quite indispensable department of the gamma graphs. Namely, it is necessary that we should be able to reason in graphs about graphs.

84

90

The reason is that a reasoning about graphs will necessarily consist in showing that something is true of every possible graph of a certain general description. But we cannot scribe every possible graph of any general description, and therefore if we are to reason in graphs we must have a graph which is a general description of the kind of graph to which the reasoning is to relate.

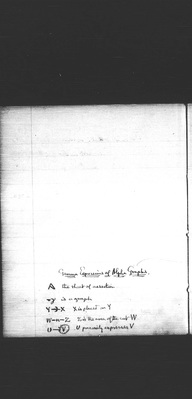

For the alpha graphs, it is easy to see what is wanted. Let [*], the old Greek form of the letter A, denote the sheet of assertion. Let —γ is a graph. Let Y[diagram]X mean that X is scribed or placed on Y. Let W–k–Z mean that Z is the area of the cut W. Let