Pages

41

82

must make sure that they are so. This “independence” that is so much insisted upon is nothing but the absence of any law of recurrence. All the good writers insist that we must assure ourselves of the independence of the “events,” as they call the instances; so that they teach that it is not enough to be ignorant of law, but that it requisite that we should make sure that there is no law of the kind is pertinent to the question. Now information of this description does not involve any kind of knowledge of future individual instances. There may be in such knowledge ground for an inference as to individual instances; but the

42

84

doctrine of chances institutes no sound inquiry into such inferences. Some writers on the subject endeavor to judge of such inferences by the principles of the calculus of probabilities; but what they say on the subject is, as I can clearly demonstrate, utterly worthless; and being so, in so far as it is apt to be accepted as sound, it is most mischievous. If a lady is afraid of going on board a steamer, it is a good argument to say to her that only one passage in thousands is accompanied by any serious harm to a passenger, and that she therefore ought not to hesitate to embark. But to say to her that the doctrine of chances teaches what it is wise to do in an individual case is a serious error of logic. Such inference is of a kind concerning which the doctrine of chances affords no direct knowledge.

43

86

All that the doctrine of chances can do is to say what will happen in the long run. For example, suppose a pair of dice to be thrown. Call them die M, and die N. Now we know that die M will turn up an ace once in six times, or six times out of thirty six, in the long run, and that die N will not only in the long run turn up a deuce once in six times, but will do so in the long run once in six of those six times out thirty six in which die M turns up an ace. Therefore, once in thirty-six times in the long run M will turn up an ace and N a deuce, and by parity of reasoning, and then once in thirty six times M will turn up a deuce and N an ace; so that deuce-ace will in the long run be thrown twice in thirty-six

45

88

or once in eighteen times.

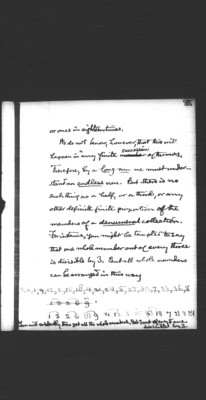

We do not know, however, that this will happen in any finite number succession of throws. Therefore, by a long run we must understand an endless run. But there is no such thing as a half, or a third, or any other definite finite proportion of the members of a denumeral collection. For instance, you might be tempted to say that one whole number out of every three is divisible by 3. But all whole numbers can be arranged in this way

1 3 2 6 (3) 9 4 12 5 15 (6) 18 7 21 8 24

You will evidently thus get all the whole numbers. Yet 3 out of every 5 are divisible by 3.