Pages

71

134

know what the facts are in regard to the habits of making up the contents of such boxes.

For that reason, I object in toto to all calculations founded upon assumptions in regard to “equal possibility”, because such assumptions are only made when we are ignorant of conditions essential to the solution of problems; and a number which is made determinate only by an assumption founded on ignorance can have no practical utility. But I am going to waive for a moment my objection to all such processes of calculation, because by doing so I shall be able to bring the force of the objection into a stronger light. Grant,

72

136

then, that we do go on some assumption of equal possibility. Still, such an assumption ought to be made on some consistent principle. Even if we are to assume some things to be equally possible I continue to object to assuming that all the different probabilities of an event are equally possible, because that proceeds on no principle that is consistent with itself. For there is no reason in assuming that the different probabilities of one event are equally possible rather than those of any other event. The distinction between a simple and a compound event is not a distinction of fact, nor a distinction having any basis whatever in objective fact. We assume any events we like to be simple

73

138

without ever dreaming of being called to account for it. Nor is there any principle on which we could distinguish between simple and compound events. What is simple and what compound depends on the wording of the problem; and nothing else has anything to do with the distinction. Now if you assume that the different probabilities of a certain event are equally possible, ipso facto the different probabilities of certain compound and disjunct events will not be equally possible. Such an assumption is therefore entirely arbitrary. There is just as much reason for supposing the probabilities of a disjunct event to be equally possible in

74

140

which case the probabilities of the first event are determined, and are determined not to be equally possible. In short, if you are going to make any assumption of equal possibility,— which I hold to be altogether unwarranted,— you ought at least to adopt some self-consistent principle in doing so. Now there is only one self-consistent principle on which such assumptions can be made; and that is that what Boole called the different constitutions of the universe are equally possible.

In making up the contents of the box of toys, the first toy put in might be dutiable D or free F. Then the

75

142

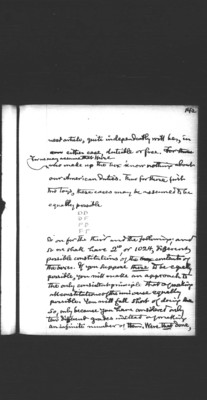

next article, quite independently will be, in either case, dutiable or free. For we may assume that those who make up the box know nothing about our American duties. Thus for those first two toys, these cases may be assumed to be equally possible DD DF FD FF So on for the third and the following; and so one shall have 210, or 1024, different possible constitutions of the contents of the boxes. If you suppose these to be equally possible, you will make an approach to the only consistent principle, that of making all constitutions of the universe equally possible. You will fall short of doing so, only because you have considered only ten different grades instead of making an infinite number of them. Were that done,