Pages

11

9

of that book made it perfectly clear to my mind that an inductive argument does not render its conclusion any more probable than it was before, using the word probable in the only sense that can give any real meaning to the doctrine of chances. An inductive argument does not increase the chances in favor of the truth of the proposition that it concludes. Indeed it is difficult to see what definite meaning can be attched to the phrase “the chances in favor of the truth of the proposition which induction infers.” If you could put all possible universes into a bag and after shaking them well up, would draw out universe

12

12

after universe, you might form statistics as to the proportion of universes in which the proposition is true. But since you cannot do that, to speak of the probability of the truth of a general proposition, to speak, that is to say, of the statistical ratio of frequency with which in the future course of experience the proposition will be found true, leaves us at a loss to conjecture what the other term of that ratio can be meant to be. It thus became plain to me that induction is something radically different in its nature from deduction; and I was thus led to ask, What is induction? I endeavored to formulate the process syllogistically; and I found that it could be defined as the inference of the major

13

14

premiss of a syllogism from its minor premiss and conclusion. Now this was exactly what Aristotle said it was in 23rd Chapter of the 2nd Book of the Prior Analytics, concerning which Grote is the best commentator. Aristotle's example is

Whatever has no bile is long-loved, Thus, man, the horse, the mule has no bile; Whence, man, the horse, the mule is long-lived.

From the first two propositions the third follows deductively; but by induction we infer the first from the second and third. With this hint as to the nature of induction, I at once remarked that if this be so there ought to be a form of inference which infers the Minor premiss from the major and the conclusion

14

16

Moreover, Aristotle was the last of men to fail to see this. I looked along further and found that having noticed in chapter 24 a particular variation of induction, Aristotle opens the 25th with a description of the inference of the minor premiss from the major premiss and the conclusion. At least, so it is natural to understand the excessively abbreviated language which he employs throughout this book. But unless a wrong word has been substituted, which might easily happen owing to the peculiar history of Aristotle's manuscripts, and which unquestionably did happen in chapter 23rd, in a place

15

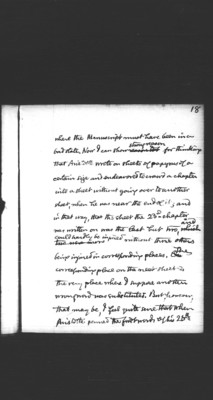

18

where the Manuscript must have been in a bad state. Now I can show strong reason for thinking that Aristotle wrote on sheets of papyrus of a certain size and endeavored to crowd a chapter into a sheet without going over to another sheet, when he was near the end of it; and in that way, that the sheet the 23rd chapter was written on was the last but two, and could hardly be injured without those others being injured in corresponding places. The corresponding place on the next sheet is the very place where I suppose another wrong word was substituted. But, however that may be, I feel quite sure that when Aristotle penned the first words of his 25th