Pages

31

50

called the circle beautiful: but it has no features: it is expressionless. No curve can be very beautiful, because the thought it embodies is too meagre. But as curves go, bicyclic quartics are as a matter of fact pleasing; and I think the reason is that they have something of the perfect regularity of the circle, with a continuity of a kind which developes special features. Hogarth's line of beauty [ ] is the simplest case of a special feature, a singularity, as it is called by geometers, which the law of the continuity itself engenders, without destroying the continuity. All this may seem to be very foreign

32

52

to logic, and perhaps it is so. Yet it illustrates the point that the valuable idea must be the eminently fruitful in special applications, while at the same time it is always growing to wider and wider alliances.

Classical antiquity was far too favorable to the sort of concept that was fortis, et in se ipso totus teres atque rotundus. I often meet with such theories in philosophical books, especially in the works of theological students and of others who draw their ideas from antiquity. Such is the circular theory, which assumes itself and returns into itself,— the aristocratical theory which holds itself aloof from vulgar facts. Logic has not the least

33

54

objection to such a view, so long as it maintains its self-sufficiency, keeps itself strictly to itself, as its nobility obliges it to do, makes no pretension of meddling with the world of experience, and does not ask anybody to assent to it.

Auguste Comte, at the other extreme, would condemn every theory that were not “verifiable.” Like the majority of Comte's ideas, this is a bad interpretation of a truth. An explanatory hypothesis, that is to say, a conception which does not limit its purpose to enabling the mind to grasp into one a variety of facts, but which seeks to connect those facts with our general conceptions of the universe,

34

55

ought, in one sense, to be verifiable; that is to say, it ought to be little more than a ligament of numberless possible predictions concerning future experience, so that if they fail, it falls. Thus, when Schliemann entertained the hypothesis there really had been a city of Troy and a Trojan War, this meant to his mind among other things that when he should come to make excavations at Hissarlik he would probably find remains of a city with evidences of a civilization more or less answering to the descriptions of the Iliad, and which would correspond with other probable finds at Mycenae, Ithaca, and elsewhere. So understood, Comte's maxim is sound. Nothing but that is an explanatory hypothesis. But Comte's own notion of a verifiable hypothesis

35

58

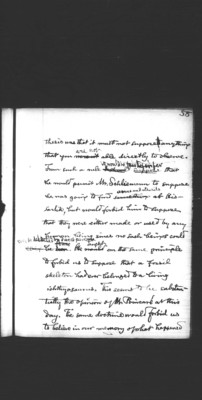

was that it must not suppose anything that you are not able directly to observe. From such a rule it would be fair to infer that he would permit Mr. Schliemann to suppose he was going to find arms and utensils at Hissarlik, but would forbid him to suppose that they were either made or used by any human being, since no such beings could ever be detected by direct percept. He ought on the same principle to forbid us to suppose that a fossil skeleton had ever belonged to a living ichthyosaurus. This seems to be substantially the opinion of M. Poincaré at this day. The same doctrine would forbid us to believe in our memory of what happened