Pages

5

1908 Oct 28 Logic 10

Suppose that you were to interrupt a discourse by the question, "Of what are you speaking?" and the reply were to be "Of something." This would be called a highly "indefinite" description. It might be a very convenient reticence for the speaker; for if he confined himself to simple predicates, nothing he said could be gainsaid. For something is white, and something is black; something is odd and something is even; and so on through the dictionary. Now think of an analogous reserve, an analogous indefiniteness, not in description merely, but in being, and you have Nothing. Nothing may be defined as that which is indistinct in being.

Again, suppose that on another occasion, the answer to the same inquiry, "Of what are you speaking?" should be "Of whatever you please." This would be called the most general description

6

1908 Oct 28 Logic 11

tion possible. The speaker could now not venture upon a single positive predicate without laying himself open to refutation. For it is untrue that "Whatever you please is black," and equally so that "Whatever you please is white;" and so on through all positive predicates. It is the predicate of a proper an assertion about "whatever you please" of any kind that is said to be general. The subject is said to be referred to per se, or necessarily. To say, "Whatever man you please to imagine" is a biped, is what we mean by saying "Man is per se a biped," or "Man is by logical necessity a biped." Now imag conceive of a that subject wh Now that of which every predicate is necessary not in description by in being is the definition of God as ens necessarium. Thus, every nameable is one of three things; either Nothing, or ens necessarium, or a thing such that of every pair of mutually contradictory

7

1908 Oct 28 Logic 12

dictory predicates one is true of it and the other untrue of it.

You cannot as yet see it, but you will see, before I have done, that we have here taken the first step toward the solution of our problem. We certainly do not say that Ens necessarium is Nothing: we say that it is incomprehensible and not to be met with in the world. As for Nothing, it is, of course, Nothing; yet it is also something. namely, a nameable idea of an idea. If you say that there is no sense, no information, in what I have been setting down writing; that is mere manipulation of words, I applaud your observation. It had to be such, in order to be pertinent to our problem, as you will see, as we go on.

Meantime, let me set down a few definitions. By the Principle of Contradiction, accurate writers for nearly two centuries have understood the principle that a pair of contradictory predicates, such as

8

1908 Oct 28 Logic 13

"is P" and "is not P" (or other than any every P) are both true only of Nothing, and not of any definite subject. Earlier writers confounded this principle with the following. By the Principle of Excluded Middle (or of excluded third,) is always meant the principle that a no pair of mutually contradictory predicates are both false of any individual subject. (Of course, to say that the twelve disciples of Jesus were all apostles or were not apostles are both false.) I believe the name was first given by Wolf: Baron Johann Christian Wolf, the systematizer of Leibnizianism.

In agreement with many logicians, but departing from the usage of grammarians in two respects. In the first place I mean by the Subject (capitalized) of an assertion or question, not the name or equivalent of a name, but or description so called by the grammarians, but that which is named, described, or referred to, to which the predicate relates. In the second place, the grammarians usually limit the term to the subject nominative,

9

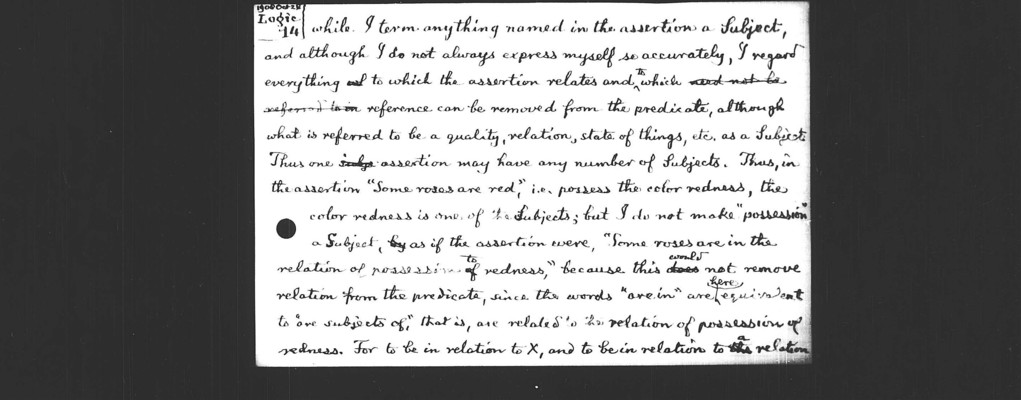

1908 Oct 28 Logic 14

while I term anything named in the assertion a Subject, and although I do not always express myself so accurately, I regard everything to which the assertion relates and to which need not be referred to in reference can be removed from the predicate, although what is referred to be a quality, relation, state of things, etc. as a Subject. Thus one assertion may have any number of Subjects. Thus, in the assertion "Some roses are red," i.e., possess the color redness, the color redness is one of the Subjects; but I do not make "possession" a Subject, by as if the assertion were, "Some roses are in the relation of possession of to redness," because this does would not remove relation from the predicate, since the words "are in" are here equivalent to "are subjects of," that is, are related to the relation of possession of redness. For to be in relation to X, and to be in relation to the a relation