Pages

10

1908 Oct 28 Logic 15

to x one mean the same thing. If therefore, I were to put "relation" into the subject at all, I ought in consistency to put it in infinitely many times, and indeed I ought this would not be sufficient. It is like a continuous line: not matter what one cuts off from it a line remains. So I do not attempt to regard "A is B" as meaning "A is identical with something that is B..." I call "is in relation to" and "is identical with" Continuous Relations, and I leave such in the Predicate. The Predicate is that part of the assertion which sign is is signified as the logical connection between the Subjects. But I sometimes term the whole set of Subjects the Subject-System.

The two classical German philosophers Johann Friedrich Herbart (1776-1841) and Gerg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel (1770-1831), both remarkably original minds, were as opposite in their qualities of

11

1908 Oct 28 Logic 16

intellect as well could be. The former seized the general point of view of logic better than almost any other German, and also appreciated the importance of mathematical relations in mental science, but had the most wooden incapacity for grasping the subtler concepts, especially those of infinity and continuity. Hegel, on the contrary, never missed the idea of continuity, and had a wonderful flair for detecting one concept as an ingredient of another, yet seldom succeeded in had a more wonderful incapacity for putting the ingredients together in the right, an incapacity aggravated by the strength of his prepossessions as to the way in which they must be connected. Both these minds, opposed as were their tendencies had the false notion that motion involved a violation of the principle of contradiction. They did not see that their difficulties were not peculiar to

12

Logic Oct 28 Logic 17

motion, but were partly due to neither analyzing rightly the idea of continuity, and partly their still grosser inability to see that an endless series of terms might be followed by a next term.

1908 Oct 29

I shall herein, I trust, lead you to understand clearly infinite series and infinite multitudes, as well as continua. But it is not yet time for that: matters must be considered in due order. Yet in advance of that, we shall soon see whether or not Herbart and Hegel can be in the right. It is plain that if they only mean that their idea of motion is a self-contradictory idea, their contention is not very important. For if it be true, it only shows that their idea of motion is only an idea of Nothing. If, however, they mean that a reasonable true idea of motion is an idea of Nothing, as it must be it is self-contradictory, then we shall

13

1908 Oct 29 Logic 18

be able to examine their contention as soon as we shall have made out clearly what we mean by knowledge, truth, and reality. Meantime, I may mention that, in regard to the (?? prior) of alternatives as to the (??meaning) or the (??) just stated just stated question just formulated as to what is meant by pronouncing motion to be self-contradictory, Herbart and Hegel are quite at odds. Herbart practically holds to the first mentioned alternative; only he persuades himself that his own idea of motion, together with those of all change and of all variety, is the only one possible,--sot that, though he is by far the more accurate reasoner of the two, he concludes that all our instinctive judgments about the world are false, which, I think you will see, is to cut off the very branch of reason upon which he is himself

14

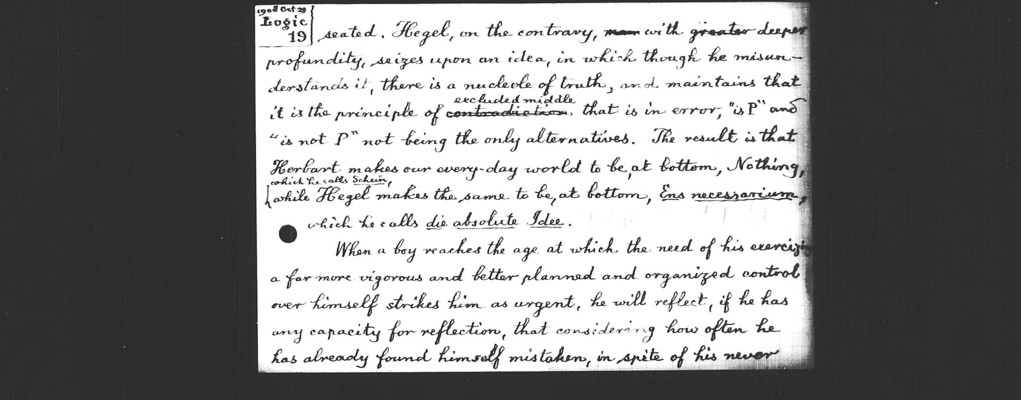

1909 Oct 29 Logic 19

seated. Hegel, on the contrary, with greater deeper profundity, seizes upon an idea, in which though he misunderstands it, there is a nucleole of truth, and maintains that it is the principle of contradiction excluded middle that is in error, "is P" and "is not P" not being the only alternatives. The result is that Herbart makes our every-day world to be, at bottom, Nothing, while Hegel makes the same to be, at bottom, Ens necessarium, which he calls die absolute Idee.

When a boy reachers the age at which the need of his exercising a far more vigorous and better planned and organized control over himself strikes him as urgent, he will reflect, if he has any capacity for reflection, that considering how often he has already found himself mistaken, in spite of his never