Pages That Need Review

MS 455-456 (1903) - Lowell Lecture II

33

26

inner line be extended to join the point on the cut, much less is asserted

This means: Somebody is a prophet and this person is not translated; that is Some prophet is not translated.

Lines of identity bring no only one new rule of illative transformation. (Illative transformation, by the way, is transformation of the nature of necessary inference.) But lines of identity require some slight changes to be made in the three primary rules already given.

Under the rule of omission and insertion, it is to be noted that a line of identity may be broken within an even number of cuts or on the sheet of assertion, while two lines may be joined within an odd number of cuts. We also have the curious fact

34

27

that as far as this rule is concerned a point on a cut is to be treated as being within the cut, although in other respects it is to be treated as being outside the cut. The cause of this is that we take it for granted that something exists. How this cause produces this effect I shall leave it for you to make out.

The rule of two cuts about the double enclosure receives an extension since not only are two cuts of no effect when nothing no graph is between them, but they are equally so when nothing is between them except lines of identity that [traverse?] the space between the two cuts.

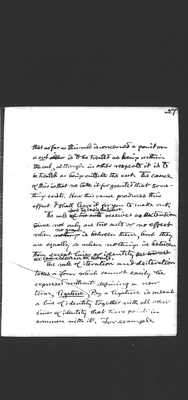

The rule of iteration and deiteration takes a form which cannot easily be expressed without defining a new term, ligature. By a ligature is meant a line of identity together with all other lines of identity that have points in common with it. For example

36

28

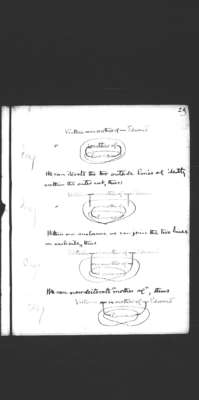

means any man loves himself. It has four lines of identity, one attached to the monad spot “is a man” two attached to the dyad spot loves and one joining the triple point to the inner cut. But all those make a single “ligature.” Now the reformed rule of iteration and deiteration is, that any partial graph, detached or attached, may be iterated within the same or additional cuts provided every line or hook of the iterated spot graph be attached in the new replica to identically the same ligatures as in the old primitive replica; and if a partial graph be already so iterated it can be deiterated by the erasure of one of the replicas which must be within every cut that the replica left standing is within. For example, suppose we have [these?] premisses

39

27 31

The first three of these mean, respectively, “Nobody loves anybody whom he does not respect,” “Somebody loves nobody whom he does not respect,” “Somebody is loved by nobody who does not respect him.” Those three propositions cannot be expressed, with the same degree of analysis without the ligature the innermost of which is within the cut that encloses both spots. But the fourth, which means “There is somebody whom somebody does not love unless he respects him” will not have its meaning changed by breaking both ligatures, as in the fifth graph, so as to make it read “Either there is somebody who non-loves somebody or else somebody respects somebody” or “If everybody loves everybody somebody respects somebody.[”] The juncture protruding through two cuts could be cut without altering the meaning

By putting two cuts round the “loves” and retracting the [junctures?] through two cuts we get the equivalent graph

The third chapter of the exposition of existential graphs is by far the most important and interesting of the three. The whole gist of mathematical reasoning depends upon it. I shall have to remit it to another

46

45

term it, compounding, the definition of it in terms of permission will be

1st, predicating the definition of the definitum, if it is permitted to scribe on the sheet of assertion a replica of a compound graph, then it is permitted to scribe on the sheet of assertion a replica of either component. Or, stating this in terms of trnsformations: Any replica of a compound graph may on the sheet of assertion be transformed into a replica of either component. That is to say, under a more practical[ly] aspect, any partial graph on the sheet of assertion may be erased or cancelled.

2nd, predicating the definitum of the

50

47

Let us now treat the scroll in the same way.

First, the predication of the definition with the definitum as subject is that when it is permitted to scribe upon the sheet of assertion a scroll with two graph-replicas, x and y, in its outer and in its inner close, or on its bottom and on it[s] patch, respectively, then whenever it is permitted to put the graph x upon the sheet of assertion, it will likewise be permitted to put the graph y upon the sheet of assertion. Or in terms of transformation it will be permissible on the sheet of assertion to transform x by the insertion into it of y as a component of a compound graph xy.

52

48

In order to put this into a shape capable more explicit shape, I will first call your attention to a corollary from it. A corollary to a proposition of Euclid is a necessary consequence drawn from it by some editor of Euclid's Elements and inserted by him, originally, I suppose, marked with a little crown in the margin. These additions are, for the most part, trifles propositions that Euclid thought not worth too obvious for special notice. Hence, any easily drawn necessary consequence of a proposition is termed a corollary. Here I will tell you a secret about necessary consequences. It is a very useful thing to know, although most logicians are quite entirely ignorant of it. It is that not even this simplest necessary consequence can be drawn except by the aid of Observation, namely the observation of some feature of something of the

53

49

nature of a diagram, whether on paper or in the imagination. I draw a distinction between Corollarial consequences and Theorematic consequences. A corollarial consequence is one the truth of which will become evident simply upon attentive observation of a diagram constructed so as to represent the conditions stated in the conclusion. A theorematic consequence is one which only becomes evident after some experiment has been performed upon the diagram, such as the addition to it of parts not mentioned necessarily referred to in the statement of the conclusion. In the present case, I am going to draw a conclusion about a double enclosure that is, two cuts one within the other and with the annular space between them blank like this The observation which I ask you to make is that