Pages

page_0001

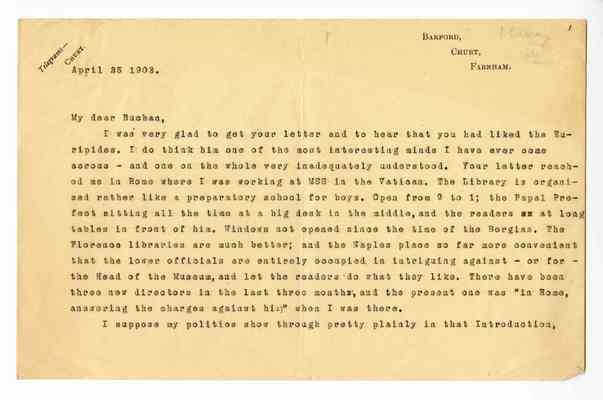

BARFORD, CHURT, FARNHAM.

April 25 1903.

My dear Buchan,

I was very glad to get your letter and to hear that you had liked the Euripides. I do think him one of the most interesting minds I have ever come across – and one on the whole very inadequately understood. Your letter reached me in Rome where I was working at MSS in the Vatican. The Library is organised rather like a preparatory school for boys. Open from 9 to 1; the Papal Prefect sitting all the time at a big desk in the middle, and the readers at long tables in front of him. Windows not opened since the time of the Borgias. The Florence libraries are much better: and the Naples place so far more convenient that the lower officials are entirely occupied in intriguing against – or for – the Head of the Museum, and let the readers do what they like. There have been three new directors in the last three months, and the present one was "in Rome, answering the charges against him" when I was there.

I suppose my politics show through pretty plainly in that Introduction,

page_0002

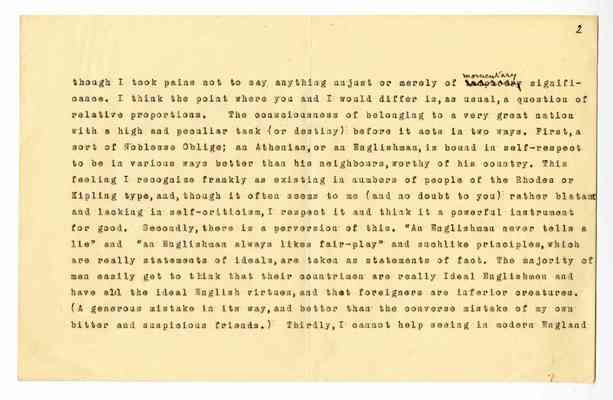

though I took pains not to say anything unjust or merely of momentary significance. I think the point where you and I would differ is, as usual, a question of relative proportions. The consciousness of belonging to a very great nation with a high and peculiar task (or destiny) before it acts in two ways. First, a sort of Noblesse Oblige; an Athenian, or an Englishman, is bound in self-respect to be in various ways better than his neighbours, worthy of his country. This feeling I recognize frankly as existing in numbers of people of the Rhodes or Kipling type, and, though it often seems to me (and no doubt to you) rather blatant and lacking in self-criticism, I respect it and think it a powerful instrument for good. Secondly, there is a perversion of this. "An Englishman never tells a lie" and "an Englishman always likes fair-play" and suchlike principles, which are really statements of ideals, are taken as statements of fact. The majority of men easily get to think that their countrimen are really Ideal Englishmen and have all the ideal English virtues, and that foreigners are inferior creatures. (A generous mistake in its way, and better than the converse mistake of my own bitter and suspicious friends.) Thirdly, I cannot help seeing in modern England

page_0003

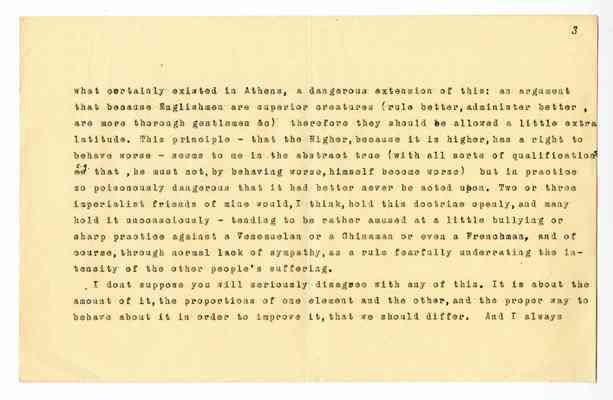

what certainly existed in Athens, a dangerous extension of this: an argument that because Englishmen are superior creatures (rule better, administer better, are more thorough gentlemen &c) therefore they should be allowed a little extra latitude. This principle – that the Higher, because it is higher, has a right to behave worse – seems to me in the abstract true (with all sorts of qualifications e.g. that he must not, by behaving worse, himself become worse) but in practice so poisonously dangerous that it had better never be acted upon. Two or three imperialist friends of mine would, I think, hold this doctrine openly, and many hold it unconsciously – tending to be rather amused at a little bullying or sharp practice against a Venezuelan or a Chinaman or even a Frenchman, and of course, through normal lack of sympathy, as a rule fearfully underrating the intensity of other people's suffering.

I don't suppose you will seriously disagree with any of this. It is about the amount of it, the proportions of one element and the other, and the proper way to behave about it in order to improve it, that we should differ. And I always

page_0004

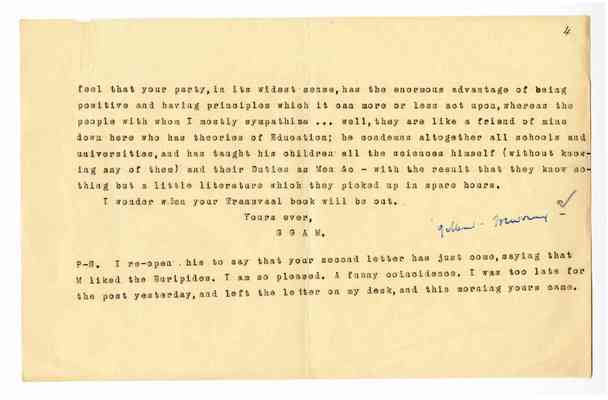

feel that your party, in its widest sense, has the enormous advantage of being positive and having principles which it can more or less act upon, whereas the people with whom I mostly sympathize... well, they are like a friend of mine down here who has theories of Education: he condemns altogether all schools and universities, and has taught his children all the sciences himself (without knowing any of them) and their Duties as Men &c – with the result that they know nothing but a little literature which they picked up in spare hours.

I wonder when your Transvaal book will be out.

Yours ever GGAM. [Gilbert Murray]

P-S. I re-open this to say that your second letter has just come, saying that M liked the Euripides. I am so pleased. A funny coincidence. I was too late for the post yesterday, and left the letter on my desk, and this morning yours came.