Pages That Need Review

Fiction: The Young Wife

12

somewhat offended by the sternness of his manners. "Nothing wonderful that a mother should forget her children," reiterated Mr. Murray. "No," said Charles, coolly; "I presume you are not always thinking of them." If looks could strike down a man, the looks of William would have felled Charles to the ground. "You have never been a father," he replied; "no, nor a husband," he added in a lower and muttered tone. Seeing Mary had not risen to take the children."Go, woman," said he, "and instantly attend to the children." "It was not I that told papa you sent us out into the rain, mamma," said the little Meta, as soon as they had left the room. "Whosoever did tell him so, told a falsehood," replied her mother, petulantly. Henry hung his head, conscious he had, under the influence of angry feelings, misrepresented what his mother had said; ashamed, yet not penitent, he muttered,"I am sure I told you a storm was coming." "Do not dare to contradict me," exclaimed his mother, catching him by the arm. "Dear, dear mamma, don't be so angry," cried Meta, throwing her arms round her neck. Mary threw herself in a chair, and burst into tears. In her passion of grief and indignation, she for some moments forgot the condition of her children. She started up and rang violently. The maid ran up. "Change these children's clothes," said she. They were taken away. She then walked the room in an agitation she could not subdue. "To command me like a servant-to reprove me as a culprit, and in the presence of my children and Charles-it is unbearable. I have, as Charles said, been too obedient, too yielding. Could not a mother's feelings have been trusted to? Oh, he little knows me-kindness might mould me to whatever he wishes-but harshness-indignity! I have submitted too long. There are limits to a husband's authority." Thus did she indulge a thousand unkind feelings, which, if not restricted, will soon grow into ungovernable passions, and tyrannize over reason and virtue. The germ of every evil propensity exists in human nature, as truly as that of noxious plants does in the bosom of the earth, unknown and unsuspected, until developed by circumstances, which call the latent principle into activity. Let not the most amiable and excellent of our race believe that there is one exempt from this innate tendency to evil. Who that knew Mary would ever have believed it possible that the malignant and vindictive feelings, now convulsing her very soul, existed in her gentle and affectionate nature. Search deeply into your own, reader, and you may, perhaps, discover that though dormant and inert, those reptile passions lie hidden there. Oh, beware of awakening them by the vivifying warmth of any indulgence prohibited by Virtue and Religion. It was a pity, a great pity, that Mr. Murray had spoken so harshly to his wife. He lamented the moment he had uttered his ungentle command, the violence into which he had been betrayed. But the situation in which he found his children-the representation of Henry-the discovery of Mary and Charles so deeply engaged, and he apparent indifference to his remostrance, had provoked him beyond all self-command. The sneering coolness of Charles' reply raised passion to its highest pitch, and no sooner had Mary left the room, that he gave vent to his long smothered feelings. "Ungrateful man!" exclaimed he, "would you sting the bosom that warmed you into life?" "Do you mean to reproach me with your benefits-then they are annulled," cried Charles. "If I am ungrateful you are mean, base--" "Stop, stop, Charles, nor provoke me farther-there are limits even to my forbearance." "You need not tell me that; your conduct to your lovely, injured wife, show these limits not to be very extensive." "Name her not-name her not," cried William, with rekindled passion, "lest you force me to command you to quite this house." "Jealous, too!" sneered Charles. "Leave my sight ungrateful wretch, ere I strike one beneath the shelter of my own roof," said William, letting fall the arm he had, in his passion, raised. "I fear you not," retorted Charles, "for tyrants are always cowards-but you shall repent of this. I go," muttering as he quitted the room; "yes, I go, but not alone." William did not hear these muttered words. He had turned to a window, against which he supported his frame, trembling and quivering with suppressed passions. What was now to be done? His wife was offended, perhaps justly offended by his harshness. The man he had loved and cherished from boyhood turned from the only home he had on earth-the kind heart of William relented. "Houseless and friendless and pennyless! Poor Charles! what will his aged parent say? She who has ever been a fond, indulgent mother to me. How wretched I have made her. And my wife, my Mary, who, in spite of all her coldness, is dearer to me that ever. Oh, I am miserable-very miserable. And where is this misery to be staid? We are all unhappy, What fatality has wrought this ruin? A few months sinse and I would have said there was not a happier family on earth. Home to me was a paradise of sweets, the sweets of pure affection. No care ever saddened the countenance of Mary-bright with love and gladness it welcomed me to the joys of home. How often has she come forth to meet me, attended by our little ones, who sported before her, literally strewing her path with flowers. How have they sprung into my arms, while hers have been thrown around us-and she has exclaimed,--'thus I encompass all my treasures!' Blessed days, and will you never return? And whence is all this change-this ruin? Alas! the serpent entered my paradise of love and joy.-Fatal error-yet could it be an error to give a shelter to a destitute? I felt it a virture-a humanity. How could I suspect-how foresee the fatal consequences. Such perfect, unbounded confidence had I in my Mary's love! Alienation of her affection! I should have thought myself criminal to have harboured such a thought! Strange, strange mystery of the human heart! And can one vicious inclination thus taint the

13

whole stream of the holy affections-maternal-even maternal. Deep and wide spreading ruin! Not an individual of this once happy family has escaped its fatal consequences-all, all wretched. But thanks be to God's protecting power, honor is still unsullied. Mary, though weak and erring, is not yet guilty." This thought stole like a ray of light into a darkened room. It soothed his perturbation, though it could not allay his distress. When Mrs. Murray learned the events of the morning, she was overwhelmed with grief-with anger; she wrung her hands and deplored her unhappy fate-reproached William, and declared she too would leave his house, and follow her poor, friendless boy. She poured her complaints into Mary's not unwilling ear; for she, too, resented the conduct of her husband to Charles. She would not appear at the dinner table-neither would Mrs. Murray, and the unhappy husband sat along, with a feeling of desolateness which words cannot describe. Lost in gloomy reverie he marked not the increasing storm-he marked not the passing hours-the day was gone, but he was still there, buried in his misery. Form this state he was roused by the sound of hurried footsteps. He started up, and opened the door to inquire what was the matter, and saw the maid hastening up stairs with a candle. In answer to his enquiry, she told him that Meta was very ill. Without waiting for another word, he snatched the candle from her hand, and springing past her, rushed into his wife's apartment. There, indeed, he saw his little girl, gasping as if for life, in the arms of her pale and terrified mother. Too well he knew the alarming sound of Meta's hoarse and impeded breathing. "She has the croup-and oh, how dreadfully; take the candle, I will run for Doctor R." The storm still raged, but he ran forth, insensible to its fury. An hour elapsed before he returned with the physician, who lived at a great distance. By the time he arrived Mrs. Murray and Mary were almost bereft of hope, and were sobbing over the little sufferer. No time was to be lost. Doctor R. caught the child from its couch, and baring its throat, cut the jugular vein. "You are killing my child!" franticly screamed Mary; as she attempted to seize the hand of the physician; but the incision was made, and the blood gushed forth. Mary stood horror-struck. She saw her clothes sprinkled with the blood of her child. She saw that child lying to all appearance dead. Some thought darted into her mind with an electrifying force, and starting, she wildly shrieked,-"I am the murderer!" and fell senseless to the ground, as if struck by some invisible dagger. Conscience has daggers. The half-distracted husband could not fly to her relief. Meta was in his arms-she had fainted-and he hung over her in the agonizing fear of her never reviving-though the physician assured him to the contrary: in breathless suspense he moved not, he spoke not-he looked not from his precious child. She breathes, breathes freely-she will live! He burst into tears, and resigning her into the arms of Mrs. Murray, hurried to his wife. Aided by Doctor R., he laid her on the sofa. Suspended animation returned, but her senses were bewildered-her exclamations wild and incoherent. "Her blood is on me! Oh, I have killed her; cruel mother-wicked mother. Kill me!-kill me!" Thus for a while she raved, until her brain was relieved by the loss of a little blood, and the administration of a composing draught. After a while she sunk into a disturbed slumber. Mr. Murray watched by her side, stealing from time to time to Meta's couch, and putting his ear close to her pale lips, to assure himself she was alive; for so softly did she now breathe, that her respiration was almost imperceptible. Doctor R. had gone; Mrs. Murray sat by the child-the light of the candle was screened. In the dimness and stillness of the room, the father and the husband, leaning his aching head on the arm of the sopha, tried to calm the turbulence of his feelings, and to reflect on recent scenes. His strongest emotion was gratitude to God for the preservation of his child. While thus absorbed in thought and feeling, he was roused by the entrance of the maid, who, crossing the room on tip-toe, whispered to Mrs. Murray, who arose and followed her from the room. Henry availed himself of the opening of the door, at which he had been long watching, and stole into the room. His father raised his finger in sign of silence, and drawing the boy to him, placed him on his knee, whispered-"Meta and your mother sleep, make no noise." The boy obeyed, and soon fell asleep on the shoulder of his father. Mr. Murray suspected whose was the loud noise he heard below; and the pulsations of his heart quickened at the idea that Charles was again beneath his roof. "How will all this end?" and he shuddered at the thoughts which passed in his mind. It was long before Mrs. Murray returned; and all below was again quiet. By the light she bore in her hand, Mr. Murray perceived she had been weeping, and looked much agitated. But she said nothing-she resumed her seat by Meta, and after ascertaining all was well, extinguished her light. All was again dark and silent. When day returned and Mary awoke from the long and deep sleep in which an opiate had bound her, it was sometime before she knew where she was. True her husband held her hand and watched beside her. But wherefore this? William tried gently to read her bewildered ideas-but suddenly starting up"I know! I know," exclaimed she "Meta is dead, and I have killed her!" Nor could she be persuaded of the contrary, until led to the bedside of her child. Meta stretched out her feeble arms, saying-"Kiss me, mamma." Mary threw herself by her side, clasped the child to her bosom, covering her pale face with her tears and her kisses. Mr. Murray fearful of the effects of such agitation on the little invalid, gently forced her from the bed. Assured of its restoration to life, she withdrew her arms, and after another fond look, turned to her husband, and clasping him round his neck, cried,"Forgive me, William-forgive me, or I die!"

14

"Be calm, my Mary," said he pressing her to his bosom, and wiping the tears from her cheek, "be calm." "I can never know peace again unless you forgive me. Oh, say that you forgive me, William!" "I do, from the bottom of my heart, I do!" Mary withdrew from his arms, and retreating to the darkest corner of the room, and falling on her knees, raised her hands, her soul to the father of all mercies. The long closed door of her heart was opened-the long dormant feeling of diving love was rekindled-the long mute voice of prayer, of praise, of thanksgiving, of penitence, again rose within her bosom. "Thanks, thanks-pardon, pardon," were the accents of that inaudible voice. Inaudible on earth but heard in Heaven, by Him who pitieth as a father pitieth his children. For several successive days Mary never left the chamber of her dear patient; she amused her when awake and watched over her when she slept. Mr. Murray had to go to his office-Mrs. Murray attended to household concerns-Henry was sent to school-Mary was alone in this silent chamber; no, not alone, for God was with her. Yes, once more she rejoiced in the divine presence, and communed with her own heart and with the searcher of hearts. She felt as if awakened from a dream-as if she had been blind, and her sight suddenly restored. The delusions by which she had so long been led astray seemed to vanish from her darkened mind, like bright meteors from the midnight sky. Yes, bright, even yet they seemed bright. The vivid emotions-the glowing fancies-the tender feelings-the full flow of ideas-the quickened intellect-the delightful imaginings-the buoyancy of spirits-the excited enthusiasm, which, in their combination, gave such a charm to her intercourse with Charles, could not be forgotten. But as companions to these pleasing images came too, the recollection of her continual consciousness of something wrong; her chilled affections for her husband and children-her neglect of every duty-the irksome restraint-the painful resource-the absence of confidence and sympathy, in her intercourse with her husband; and then, (oh, how she blushed at the recollection,) the embittered, the angry feelings that finally destroyed her peace and made her wretched. "And all," thought she, "all the raptures and all the torments I have experienced arose from deep and damning sin. No wonder I could not reconcile such contradictory feelings-such conflicting duties. Brother! oh, fatal cause of my error. I called him brother, though I felt not like a sister. Yet veiling my feelings under this specious disguise, I deceived my own heart, and silenced the murmurs of conscience! But the veil has fallen from my eyes, the shock by which it was torn away was severe, but effectual. Oh, on what a precipice I stood,-how smooth and flowery was the path leading to it. Thy hand has staid me, gracious God; rebellious as I have been, thy power was not forgotten. Had it not been for they felt presence-for a deep conviction of my responsibility to thy holy tribunal, what a lost and guilty creature might I now have been! Guilty! oh, I am guilty-but not lost, irremediably lost! Humble me-correct me-afflict me, but abandon me not, oh! my heavenly father!" In such exercises of the soul did Mary pass the silent and solitary hours of many days. A [burthen?] seemed lifted from her heart, and its natural affections flowed forth in a stream full and pure. A renewal of confidence and frankness once more united her to her fond and indulgent husband. He not only forgave but forgot the errors of one so dearly beloved. The vivacity of first love could not be restored; but a more enduring, though a more tranquil sentiment supplied its place. Meta recovered and was never again neglected by her now devoted mother. Henry was kept at school all day, but returned at its close to enliven and gladden all the family-but most especially the little Meta. Charles after several ineffectual attempts to have an interview with Mary, departed for the far west, and in the stirring scenes of wild adventure, met an early grave. Old Mrs. Murray long mourned what she called his banishment; but when she learned all the evil he had caused, no longer reproached Mary with unkindness. Peace, which like a dove scared from its nest, had fled from her bosom, once more returned and blessed the home of Mary, and she learned from experience the truth declared by the Christian moralist, that "If you allow any passion, even though it be esteemed innocent, to acquire an absolute ascendant, your inward peace will be impaired. But if any which has the taint of guilt take possession of your mind, you may date from that moment the ruin of your tranquillity."

Fiction: Who is Happy?

1

WHO IS HAPPY? Smith, Harrison [i]Lady's Book (1835-1939);[/i] Apr 1839; American Periodicals pg.157

Written for the Lady's Book.

WHO IS HAPPY?--(CONTINUED.)

BY MRS. HARRISON SMITH.

[left column] A young relation of Mr. De Lacy;s became an orphan, and by the death of his parents was left destitute and homeless. My husband, rigid in his ideas of duty, determined to adopt and provide for his relative. He became an inmate of our family; he was about my age, and was received in the family as a brother. Placed in this character and situation, I treated him with the kindness and frankness such relationship was calculated to inspire. He was not hand some, but he was interesting. He was not distinguished by intelectual endowments, or personal graces, but his extreme tenderness of disposition, and acuteness of sensibility, gave a refinement and delicacy to his manners, which generally is the result of a highly cultivated mind. A tincture of melancholy, added to his natural diffidence, could not fail of exciting a tenderer interest, than a stronger or more self sustained character wold have done. Gratit ude to his benefactor, he felt to a painful de gree; and sought by the most assiduous and unremitting attentions to discharge some portion of the obligations with oppressed him. His relative afforded him few opportunities of evinc ing his grateful feelings; for my husband, suffi cient to himself, seemed as little desirous of receiving, as he was attentive in paying, those small, but kind assiduities, which constitute the language of sentiment; he lived apart from, and I may say above others; and, steadily, loftily, and alone, pursued the path he had chosen, with a mind so fixedd on highter objects, as to be in different to the little pains and pleasures of private life.

It was natural for the young man, thus rep elled by the coldness of his relative, to turn those attentions, prompted by gratitude, to the wife and child of his benefactor. But there was no reflection or calculation in this conduct--it was the instinct of a tender heart, full to over flowing.

Domestic in his habits, pure and simple in his tastes, and naturally fond of children, he was never tempted to look abroad for pleasures, since all he desired were found at home. Even had this not been the bias of his disposition, the governing sentiment of his soul would have prompted him to devote his time to the family into which he had been so generously adopted. At any rate, he could not but love my little Clara. This darling child had now become my inseparable companion--no longer confined to the nursery, but the delight and plaything, and I may say, the pride and ornament of the par lour--for what was there I was so pround of ex hibiting, as by beauteous Clara? Yes, her infantine loveliness made her the admiration, and her good humour and vivacity, the delight of all our visiters.

Even her father used sometimes to be drawn from his abstraction, and would pat her head and kiss her cheek: but, if encouraged by this

[right clolumn] degree of notice, she attempted to climb his knee or prattle, he would gently push her back, saying, "Away, little one, you disturb me."- How could he resist her winning ways?--Ed ward, on the contrary, never entered the room without catching her in his arms, and lavishing on her the fondest caresses. He would play with her for hours together; sugar plubs and toys were always in his pockets, which he taught her to search; I should have grown jea lous of the dear child's excessive fondness for him, had not my maternal love been so much gratified by his devotion to her.

When I walked, Edward walked with me, while the nurse followed with the child. When at home, his own engagements were given up that he might read to me, or play with Clara.

How often during the long twilight of winter evenings--fire-light, I should rather say--have we both sat on the arpet and amused the dear child, or while I played on the piano, he would dance with her; and when the nurse came to take her to bed, to humour the petted darling, he would himself carry her to the nursery door, or at other times walk her to sleep in his arms. Kindness to a child is the readiest way to a mother's heart, and to such an one as mine, it was a short and easy way.

My home was no longer desolate--affection and sympathy were now its inmates. I suffered not from the aching void which had so long gnawed upon my heart, like hunger on the famished wretch; it was now full to overflowing of kind and gracious feelings. I made another happy. Delightful consciousness! The happi ness that beamed from Edward's face, was to my long chilled and darkened soul, like the summer's sun, after a dreary winter.

Every faculty seemed to revive under the animating infuence of cordial symathy. In tellectual pleasures were eagerly pursued, as I ardently desired the improvement of this amia ble young man. I had now a motive for select ing and reading the best and most useful works, and soon felt the beneficial effect on my own mind, though the motive of my choice had only been the improvement of his.

Where were now that lassitude, restlessness, and dissatisfaction, that had made my life a burden heavy to be borne? The awakened activity of thought and feeling gave wings to those hours, that hitherto had crept so wearily along.

Ah, my husband, had I been necessry to [i]your[/i] happiness, there would never have been a deficiency in my [i]own.[/i] The consciousness of pleasing imparts the power to please, whilst a failure so to do, destroys not only the power, but the motive which impelled endeavour. The moral, is like tha material world--warmth es pands--cold contracts. The revivifying effects of spring are not more obvious on the earth which it clothes in verdure and flowers, than

2

the benign influence of affection on my dispo sition, which it restored to cheerfulness and activity.

But this renovated felicity was not of long duration. My child was seized with a sudden illness which threatened its life. During five nights and five days, I never closed my eyes, or withdrew them from the face of the precious sufferer.

Every morning before my husband went out, every night before he retired to his chamber, he would come and stand beside her, feel her pulse, inquire what prescriptions had been made, then bidding me good night, advise me to be calm and control my feelings. How strange was the contrast offered by Edward's unwearying solicitude and attention. A spectator, ignorant of the truth, would have taken him for the fa ther of the dear little creature. For hours would he kneel by her bedside and soothe her restlessness—administer her medicine, and smooth her pillow.

During her convalescence, she, like all chil dren, was wayward and fretful. With what gentleness, what patience and kindness, did this amiable friend attend on her. For hours and hours would he carry her in his arms, and caress and amuse her. It was not in human nature to resist the influence of such goodness. It was a brother's love—at least, it was with a sister's purity! I will acknowledge that the comparison of his to my husband's conduct at this period, often forced itself on my mind, greatly to the disadvantage of the latter. I should have controlled my thoughts, and not allowed them to dwell on this painful subject. Such a comparison was worse than useless. It excited too much irritation against one—too grateful a tenderness for the other. I struggled against these feelings and argued against my own convictions. But facts were stronger than arguments, and feelings were stronger than either.

Let no human being, but woman least of all, depend on their own strength of resolution to resist temptation—especially when it comes clothed in the garb of innocence—assuming the form of friendship, and accompanied with qua lities congenial with our own dispositions, or such as we respect and admire. Were vice to appear in its own hideous form, it would never be dangerous. It is, when wearing the sem blance of virtue, that we yield to its allurements. With what specious pretences and seductive motives does the deceitful heart excuse its wan derings from the strait and narrow way of duty. The diverging paths are strewed with such fair flowers that we respect not the snares that lurk beneath.

Of all the petitions contained in the prayer taught us by the blessed Jesus, there is none we should oftener repeat than deliver us from temptation. He knew our nature, and wherein our greatest danger consisted.

Oh, guard against temptation, however sweet its voice, or lovely its form. In avoidance alone is safety. The strongest are sometimes weak— the bravest have quailed before danger—the most determined, at times, have been irreso lute—the most virtuous have erred.

No one knows himself until he is tried.

Peter denied his Lord. With all the fervent zeal, the daring intrepidity, that impelled him to risk his life in his master's defence, he could not resist the imputed shame of being the follower of the insulted and persecuted Jesus. After such an example of frailty, who dare con fide in themselves?

For a long while I suspected not that I or my young friend were in any danger; and when the suspicion was awakened, I felt a pride in braving it, recollecting what I had both heard and read, that no woman could be called virtu ous, until her virtue had been tried. I rejoiced that mind should be put to the test, in order to enjoy the pride of triumph.

Dangerous experiment! Seldom made with impunity, and never without suffering. But I did gain the victory—thanks, most humble thanks to that superintending providence who watched over, and guided me through the perils which I had so rashly dared. Not to me—not to me is the merit due.

In the dreadful conflict between passion and duty, I must have fallen, had not the felt pre sence of a heart-searching and all-seeing God re strained and governed my own secret actions— governed them, when human laws and human motives ad lost their controlling influence.

Yes, I came off conqueror; but it was a con quest that cost me my peace—my health—al most my life—for I was brought to the very verge of the grave.

And my poor, unhappy friend!—But for me he might have been happy and affluent. His sole dependence was on his benefactor, and in leaving him, he sacrificed all his bright pros pects, and went forth from a sheltering roof, into a cold, unfriendly world. But duty required the sacrifice, and he did not hestitate to make it.

Would that I could deter others from running the same risk I did. To accomplish such a purpose, I would tear open the wounds that time has long since healed—I would describe the restless hours—the wakful nights—the dark purposes—the stormy feelings—the acute anguish I endured. I would, in short, describe the conflicts that distracted me, and compared to which, the state in which I had long lan guished, might have been deemed happiness. Grievances inflicted by the faults of others, are light in comparison with those inflicted by our own errors. Conscious purity and rectitude afford the mind a strong support under the pressure of injustice or unkindness, and diffuse a self-complacency, an inward peace, without which there can be no true enjoyment, however splendid the condition, or luxurious the plea sures, or various the amusements in the world can bestow.

There is a bitterness in guilt that mingles with the sweetest draught she ever administers to her votaries—while in that virtue, there is a sweetness which overpowers the bitterest drop that human sorrow can infuse in the cup of life.

Yea, the indulgence of any dominant passion, though it lead not to actual guilt, is fatal to the bosom's peace. But where there is an accusing

Lucy (chapter_22)

1

Chapter 25

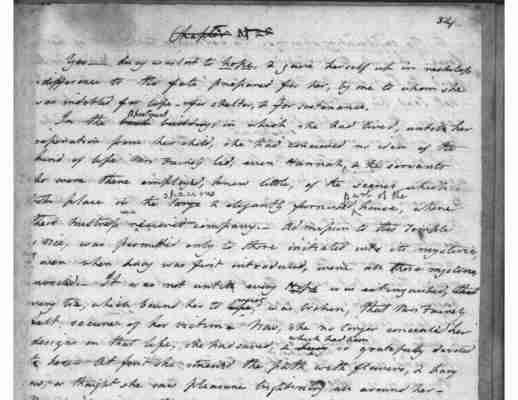

Yes - Lucy was lost to hope, & Jane herself up in [illegible] difference to the fate prepared for her, by me to whom she was indebted to for life - for shelter, & for sustenance.

In the back building apartment, in which she had lived, until her separation from her child, she had conceived no idea of the kind of life Mrs [Fainely?] led; even Hannah, & the servants who were therre employed, knew little, of the scenes which

Anna_Maria_Thornton_Visiting_Book (1792-1834)

2

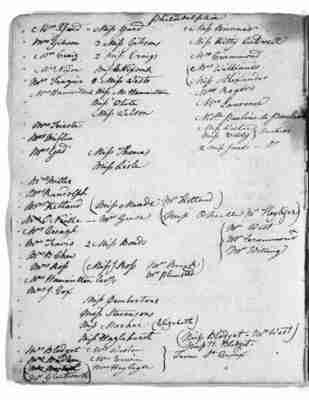

Philadelphia

+ Mr[s?] [Y?]ard - Miss Yard + Miss Bummer + Mrs Gibson 3 Miss Gibson + Miss Kitty Caldwell + Mrs Craig 2 Miss Craig[s?] Mr [C?]rammond + Mrs Nixon Miss E Nixon Mr Williams + Mrs Frazier 2 Miss We[th?] Miss Alexander + Mrs Hammiltone Miss M. Hammilton Mrs Rogers + Miss White Mrs Lawrence + Miss Wilton + Mrs Frieste Mlle Pauline de Pauleon + Mrs Miflin Miss Wishar } Quakers Miss Eddy } + Mrs Gad Miss Thomas 2 Miss Jones - Do + Miss Lisle + Mrs Miller + Mrs Randolph + Mrs Kettand (Miss Meade Mrs Kettand) -- Mrs Giese (Miss Oneill Mrs Heyliper) + Mrs Creagh { Mrs West + Mrs Travis 2 Miss Bonds { Mrs Crammond + Mrs [B?] Chen {Mr Willing + Mrs Ross (Miss Ross Mrs Breck) + Mrs Hammilton [Tecks?] Mrs Plumsted Mrs J. Cox + Miss Pembertons + Miss Stevensons + Miss Maz[k?]oe (Elizabeth) + Miss Hazlehurst (Miss Blodget - Mr West) Miss H. Blodget Mrs Weston } From St. Croix + [?] Mrs Erwin } +Mrs Heyliger } (Mr Glintworth)

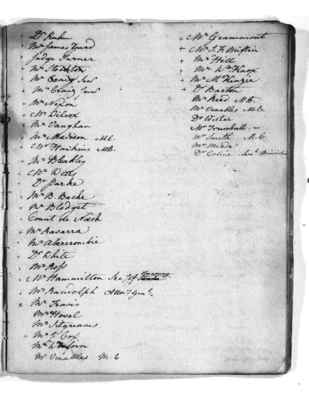

3

Dr Kirke Mr James Yard Judge Turner Mr. Stockton Mr. Craig Senr Mr. Craig Junr Mr Nixon Mr Wilcox Mr Vaughan Mr Madison M.C. Mr Hawkins M.C. Mr Bleakley Mr Wells Dr Parke Mr B. Backe Mr Blodget Count de Nash Mr Ravarra Mr Abercrombie Dr White Mr Ross Mr Hammilton Secy of State(crossed out) Treasury Mr Randolph Attory Genl Mr Travis Mr Howel Mr Sitgreaves Mr. J. Cox Mr. Worfoin Mr Venabels M.C. + Mr Grammont + Mr J.F. Miflin + Mr Hill + Mr Wm Knox + Mr McKinzie + Dr Barton Mr Reed M.C. Mr Venables M.C. Dr Wistar Mr. Trumbull.— Mr Smith. M.C. Mr Meade Dr Coline Secet Minister

Margaret_Bayard_Smith_to_Unknown_undated

1

Wednesday

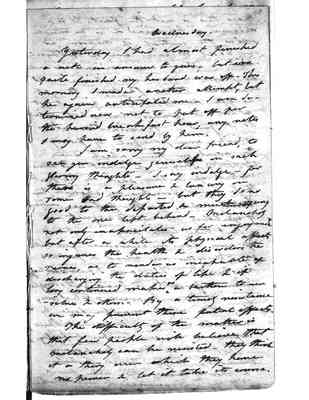

Yesterday I had almost finished a note in answer to yours, but [ere?] quite finished my husband was off - This morning I made another attempt, but he again anticipated me - I am de termined now not to put off per this hurried breakfast hour, any notes I may have to send by him.

I am sorry my dear friend, to see you indulge yourself in such gloomy thoughts - I say indulge - for there is a pleasure and luxury in some bad thoughts - but they do no good to the departed & much injury to the one left behind - Melancholy not only incapacitates us for enjoyment but after a while its physical affects so injure the health & disorders the nerves, as to render us incapable of discharing the duties of life & if long continued makes us a burthen to our selves & others- By a timely resistance we may prevent these [fatal?] effects.

The difficulty of the matter is that few people will believe that melancholy can be resisted- they think it a thing over which they have no power & let it take its course.