Pages

MS01.01.03.B01.F13.001

Few episodes in American history have had such a far reaching effect on matters pertaining to the socie-cultural plight of Blacks in the Western world as did the Amistad Incident. n many ways the attitude of firm in 1839, Wen Cinque and his ardent followers took command of the Amistad,Joshua Johnston,honeof the earliest hadhimself left behind a record of accemplishment in the formative art of panting equal to the which received had as early as 1796. the praises of the wealthiest patrons or the city or Baltimore.An accurate register of the gifted would artisansof Colonail America inclunder Black crafsmen and skilled lanorers who brought to America the artistry of their forelathers from Africa. The religious and social customs which called for the use of art in everyday living in Africa were destroyed by the same system of slavery our attention scholarly which brings to light the Amistad Incident as a subject of interest. The slavemaster paayed an important role in the deliberate attempt to discourage the use of African forms in language arts as well as in visual and motive expression. We was successrux He succeeded in his effort to prohibit the use of native art in religious rites and social ceremonies signaled the emergence of a rather unique form of in the usual arts which sophistication in the arts visual arbs which paid homage to both African and western styles of making. Those persons who followed this practice of merging the arts of these two different societies must be looked upon as masters of universal forms as they redirected the passage of an African icenegraphy in art into one which became serviceably ariented in colonial America.

The art that has been produced by Americans of African ancestry can be regarded as a synthesis of several forms of expression. The sources and roots of these expressions are numerous in origin but emphasis on black heritage history and African heritage have dominated the content of

MS01.01.03.B01.F13.002

2

much of the work that black artists have produced during the past decade. More recently, regional American styles such as the new realism, the colorist tradition in art, the conceptual and pop movements are dominant trends that are to be seen among black artists [deleted: who work] working today. Of equal importance is the ever-present trend of contemporary AfroAmerican art to be literal in the interpretation of themes depicting current black life-styles. Artists who work in this literal and rather traditional manner often use their art as a means of focusing attention on their social plight [deleted: life and indeed the life of] and the plight of black masses as a whole, thereby showing the injustices that [deleted: accompany] are associated with being born black in America.

Traditionally, the black artist has been observed from a distance by critics and historians alike. He has been called upon by the majority culture to perform in the arena of European-centered art and has been conditioned to believe that he at best is a queer participant in an American sub-culture.

Some students of American culture suggest that Afro-American art exists in order to appease the mistakes of white historians and critics who have been systematically responsible for the emissions of the accomplishments of artists of color from their writings. A more positive meaning of Afro-American art centers around the notion that the Black Experience provides artists of all media with a particular insight into the nature of their own life-styles, thereby giving each artist something special to say about being a Black American. The history of slavery in America, the civil rights struggle of the 50s and the 60s along with the socio-political structure that often excludes Black Americans from the American mainstream are vital experiences upon which many black artists have turned [deleted: to] for content. However, in order to be as comprehesive as possible in [deleted: my] an objective coverage of the subject, this Writer shall hereafter refer to Afro-American art as being "all accepted forms of visual expression that are practices by persons of African ancestry who live in America."^1

MS01.01.03.B01.F13.003

2. [DELETED TEXT: the delineation of movements among black artists but as a whole. The Speakers will...I shall be addressing myself..themselves.. to this subject as though it were based in a socio-cultural definition. Otherwies, one asks the serious question, "why African-American or Black art in the final quarter of the 20th century".]

Only in recent years has there been a general trend toward the positive identification of a racial type which [deleted: has] contains certain iconographic forms peculiar to black artists. This trend is presently moving towards the making of an aesthetics which is recognizably black in content and style, [DELETED TEXT: In the course of this lecture, I shall attempt to point out some of those visual trends that reoccur over and over again in African-American art] thus establishing a pattern of form peculiar to the making of black symbols. However, in order to more clearly establish the premise of a particular racial type in art, one must look closely at the people who make it and look more specifically at those who use it. In so doing, we witness two distinct historical trends in the development of the art produced by African-Americans that form the basis for the distinct direction that one sees in what may rightly be called African-American art.

First, there is to be found a limited number of [deleted: visual] art forms that, without a doubt, identify themselves as African survivals -- having a direct relationship to visual forms currently in use in West African culture. [deleted: in the past and present today] These forms allude to the individual involvement of the African in the new world and establish what might rightly be referred [deleted: I wish to refer]

[IN THE LEFT-HAND MARGIN]

R-1 (African House Melrose 1747)

L-1 (Contemp. House Kenya)

MS01.01.03.B01.F13.004

to a visible presence. Secondly, there are those visual forms that have been made by Americans of African descent with the conscious effort in mind of imitating the surface reality of a functional form from Africa without adhering to any cultural principle governing the making of such forms in African societies. These forms sanction and affirm the symbolic presence of Afr0-American culture in the visual arts and illustrate the firm historical roots of black heritage even in our own time. It is in the latter trend that one finds the adherence to a formal style of making in art that has become popularly known as "Black Art". Those visual forms which are grounded in this concept of a symbolic presence achieve a new formal expression in format similarly to that art produced by European artists who saw African art for the first time at the turn of the century, at which time, the formal dynamics of African art were copied without regard for traditional societal and symbolic function. It is now evident that the Afro-American artist, by relying upon the formal dynamics of African art as the sole pattern for his new iconographic expression, also creates a new symbol by exercising what the late Dr. Alain Locke referred to as "the return to the ancestral arts of Africa". This return must then be understood through the symbolic presence of Afro-American culture as a whole and not equared with a physical presence of AFrican art in America. History reveals to us that the black man brought with him from Africa an amazing number of skills that could be

MS01.01.03.B01.F13.005

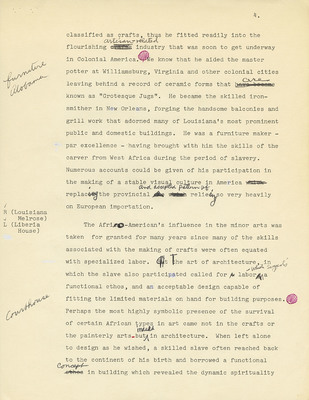

classified as crafts, thus he fitted readily into the flourishing artisan-related industry that was soon to get underway in Colonial America. We know that he aided the master potter at Williamsburg, Virginia and other colonial cities leaving behind a record of ceramic forms that are known as "Grotesque Jugs." He became the skilled iron-smither in New Orleans, forging the handsome balconies and grill work that adorned many of Lousiana's most prominent public and domestic buildings. He was a furniture maker - par excellence - having brought with him the skills of the carver from West Africa during the period of slavery. Numerous accounts could be given of his participation in the making of a stable visual culture in America replacing the provincial and accepted pattern of relying so very heavily on European importation.

The Afro-American's influence in the minor arts was taken for granted for many years since many of the skills associated with the making of crafts were often equated with specialized labor. The art of architecture, in which the slave also participated called for labor which suggests a functional ethos, and an acceptable design capable of fitting the limited materials on hand for building purposes. Perhaps the most highly symbolic presence of the survival of certain African types in art came not in the crafts or the painterly arts, but indeed in architecture. When left alone to design as he wished, a skilled slave often reached back to the continent of his birth and borrowed a functional concept in building which revealed the dynamic spirituality