Pages

MS01.01.03.B02.F10.011

-9-

slaves, to aid his craftsmanship. He, like Marie Tèrèsa Quan Quan, owner of Yucca House, now a part of Melrose Planation near Natchitoches, Louisiana in the eighteenth century, owned more slaves than the average white slavemaster and no doubt felt comfortable within his social setting.

A unique and interesting aspect of Day's work is revealed through the unusual patterns and motifs that embellish numerous stairways and architectural interiors that he constructed. One handsomely carved post at a stairwell ending takes on the likeness of an African statuette. Another stairwell is gracefully ended by stationing a well designed post underneath the railing which ^[creates a pattern that] may very easily be associated with the Chi Wara ^[antelope head] of the Bambara people of Mali. Two masks serve as guardians on the mantle posts of a fireplace in a Milton home that recall the classical treatment seen in ^[a] Baulè mask from the Ivory Coast. However, there are no records of proof which indicate that Day was at all acquainted with any of the African art forms to which his work has been compared even though one is at a loss to explain their similarity.9 His death is recorded as 1861, a few years following the failure of his business.

Dutrevil Barjon of New Orleans was not as well know as Tom Day but^[it] is evident that his furniture was admired and purchased by men of wealth throughout the Delta region. An 1822 edition of the New Orleans City Director {Paxons} lists him as a "free man of color", having the profession of furnituremaker. During the same year, his furniture business was advertised in the following manner:

Furniture warehouse [underlined]

Articles of Furniture made in this city No. 279 Royal Street Between Main and St. Phillip

"The subscriber having enlarged his establishment offers to the public a large assortment of furniture made in this

[line] 9 Jones, Op.Cit., P. 64.

MS01.01.03.B02.F10.012

-10-

city, and in the newsest and most fashionable style. He will constantly keep on hand a complete assortment of chairs, looking glasses and other articles which he will sell cheap.

The subscriber will promptly attend to any order for the city or county, and will take the greatest care in the packing up of articles forwarded by him." 10

Word of the black artisan's agility and workmanship in the craft of the ironsmither brought scores of wealthy whites to the slave markerts in Charleston, Mobile, Savannah, Baltimore and New Orleans in search of black talent that could be used to aid in the forging of grillwork and the making of wrought iron balconies for the adornment of homes, businesses and public buildings alike. See figure

Persons of color who worked under tutelage of well-known white architects in colonial times often achieved the distinction of being permitted to work on their own in later life even if they have not been [strikethrough: given] granted their own freedom. [strikethrough: They] Their visits [strikethrough: were thus] to the wealthy homes as workers allowed them to be exposed to the very best that could be found in [strikethrough: furnishings and the] [strikethrough: domestic arts of the home] home furnishings. Some of these artisans no doubt kept in mind the designs of their homes that they had been forced to leave behind when they were brought to America [strikethrough: under the bondage of slavery] as slaves. In some specific cases these designs figured well into the plans of the newly emerging plantation style of architecture in various parts of the South, but most particularly in Louisiana.

There remains to this day a few fine examples of buildings that [strikethrough: without] [strikethrough: doubt] are closely related in structural design and formal appearance to particular West African architectural building styles. Noteworthy among these remaining architectural structures that show definite African influences in design are three houses ^ [situated] on what is presently called Melrose Plantation

[line] 10 Newspaper Advertisement, name of paper not given, Historic New Orleans Collection.

MS01.01.03.B02.F10.013

-11-

located ^ [on the Cane River] near Natchitoches, Louisiana. Built in the late eighteenth century by a former slave, Marie Thérése Quan Quan, two of the remaining structures, one of which was originally called Yucca House, can be directly linked to certain rectangular shaped houses in Bamelike-type sloping roofs that are common to the regions of contemporary Zaire and the Cameroons. The Bamelike house of the Cameroons, which used rammed earth walls for support, provided [strikethrough: a] the model for one building now called African House. 11 See figure

The round slave quarters, ^ [figure] constructed on the site of stately Keswick Plantation near Midlothian, Virginia ^ [also] provides us with a very fine example of the cylindrical or beehive house often [strikethrough: employed] constructed by Africans who live in the rain forest. Constructed of brick, the Keswick slave house still retains a specific African format in appearance and has in addition to its basic structural pattern a central fireplace which served [strikethrough: the] a dual purpose of heating and ^ [for] the preparation of food. Even though one finds similar buildings existing in France, the pigeonnier, ^ [See figure] a structure which was normally build adjacent to stately houses in Louisiana such as Labatut, Parlange and Melrose, shows a definite kinship with the above mentioned cylindrical house in Africa. *

The transformation which took place between the artisan skills of good craftmanship and black involvment in the fine arts of engraving on metal plates, painting on canvas and sculpting forms for aesthetic enjoyment came about during the more than 150 years after black immigrants were forcefully brought to America. The sophisticated method of expressing visual images through the graphic media of printing and painting were not foreign to the artisan tradition in Africa since these forms of expression were found [strikethrough: to be] in

11 Driskell, David C., Amistad II, Afro-American Art Board of Homeland Ministries, New York, 1975, p. 39.

MS01.01.03.B02.F10.014

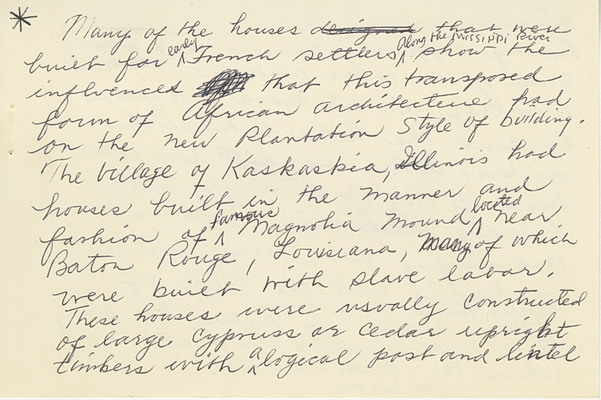

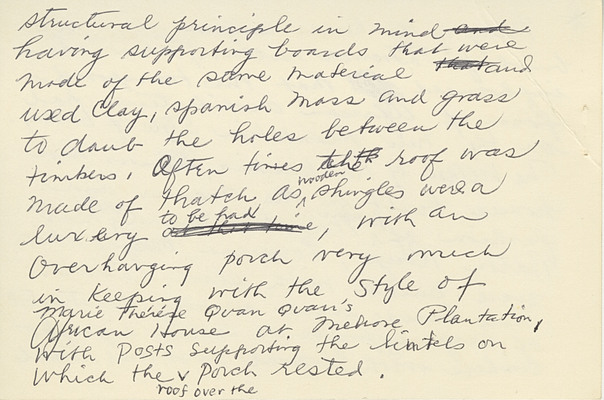

* Many of the houses [strikethrough: designed] that were built for ^ [early] French settlers ^ [along the Missippi River] show the influences [strikethrough: of] that this transposed form of African architecture had on the new Plantation Style of building. The village of Kaskaskia, Illinois had houses built in the manner and fashion of ^ [famous] Magnolia Mound ^ [located] near Baton Rouge, Louisiana, [strikethrough: Many] of which were built with the slave labor. These houses were usually constructed of large cypress or cedar upright timbers with ^ [a] logical post and lintel[?]

MS01.01.03.B02.F10.015

structural principle in mind [strikethrough: and] having supporting boards that were made of the same material [strikethrough: that] and used clay, spanish moss and grass to daub the holes between the timbers. Often times the roof was made of thatch as ^ [wooden] shingles were a luxury [strikethrough: at that time] to be had, with an overhanging porch very much in keeping with the style of Marie Thérése Quan Quan's African House at Melrose Plantation, with posts supporting the lintels on which the ^ [roof over the] porch rested.