Pages

MS01.01.03.B02.F10.031

[crossed-out: -22-] 27

concerning the intellectual inferiority of Blacks from the minds of persons of liberal thought who saw art to be an act of the highest manifestation of the human spirit. Perhaps, it was in this sense that the artist felt his mission in life to be one devoted to the cause of making art instead of a cause which used art to carry a social message. [crossed-out: His] Duncanson's artistry registered the poetic romance of color and form that abound in a world he saw divided between fantasy and truth. His paintings echoed the temperament of the time, showing first a developmental trend toward the sanction of portraiture as the genuine American art form. His then controversial painting, UNCLE TOM AND LITTLE EVA, 1853, which was inspired by the writings of Harriet Beecher Stowe, perhaps the most visible evidence he gives of pictoral sympathy of any kind for a black subject, is superimposed over a dreamland setting where nature takes precedence over the central theme of Little Eva and Uncle Tom. According to an article which appeared in the Detroit Free Press in 1853, the painting illicited caustic remarks from one writer for the Cincinnati Commercial Gazette, who upon viewing the work, labelled the subject of his commentary about the painting "AN UNCLE TOMITUDE". The writer accords..."A very stupid looking creature"... to Uncle Tom and describes Little Eva in less glowing terms than those which weregiven her in [crossed-out: the] Mrs. Stowe's novel. [crossed-out: 23] 26 But Duncanson was bound to receive criticism of a more valid and objective nature as he then turned his painterly eye more succinctly to a romantic portrayal of the land he loved both real and fictional. [Typed underline] [crossed-out: 23] 26 The Cincinnati Commercial Gazette quoted in The Detroit Free Press, April 21, 1853, p. 2, col. 3.

MS01.01.03.B02.F10.032

[header: [crossed out: 23] 28]

Landscapes were the dominant subjects chose by the artist thereafter with the exception of a few compositions such as Faith, 1862 and THE HIDING OF MOSES, 1866. Both works show an eclectic leaning toward the neo-classic style of painting to which he had been exposed in Italy and other European countries.

In 1867, Duncanson returned to Cincinnati and began exhibiting works he had done in Scotland and others that he painted from memory. At this time the artist [right margin: stylistically] broke with the Hudson River School which exhibited a concern for the[editing mark: /]real image [right margin: of nature.] [crossed out: and placed] [insert: ally? He then began placing] more emphasis on elements and scenes bordering on fantasy in his paintings. He exhibited an altogether refreshing style that was his very own. Duncanson made one last trip to Scotland between 1870 and 1871 as suggested by some of his late paintings of Scottish scenes: Dog's Head Scotland, [crossed out: 1870,] Ellen's Isle, [crossed out: 1870,] and Lough Leane, [crossed out: 1870.] [insert: all of which are dated 1870.]

By the summer of 1871 Duncanson returned to America to exhibit his Scottish works. They were well received and [crossed out: gave] [insert: there were] indications [crossed out: of a promising future for the artist] [insert: that he would finally be received as an important painter.] His paintings were bringing up to $500 each and he enjoyed favor and the deserved respect of his peers. At this point in his life, when opportunity and the future seemed brightest, Robert Duncanson feel ill to a sickness that three months later was to end his life. He died December 21, 1872, in Detroit. Five days later, the artist's obituary as published in a Detroit daily which reads as follows:

"DEATH OF DUNCANSON THE ARTIST - On Saturday last Robert S. Duncanson, a celebrated artist of this country, died at the Michigan State Retreat, on Michigan Avenue, and his remains were interred on Monday last. He came to this city about three months since, and has been a patient in the above institution most of the time since. He had acquired the idea that in all his artistic efforts he was aided by the spirit of one of the great masters, and this so worked upon his mind as to affect him not only mentally but physically. He was 55 years of age, a man of modest and"

MS01.01.03.B02.F10.033

29-

retiring disposition, and a gentle man who was greatly esteemed by all who knew him. He was born in New York and for the past 30 years made Cincinnati his home. The honors received by him both at home and abroad are numerous. He paintined the "Land of the Lotos Easters," after Tennyson's poem, and when he visited Europe the poet laureate received him at his residence as a recognition of his appreciation of that great work. He also painted his "Recollections of Italy," an exceedingly complete production, and another of his greatest efforts was his painting of the "Paradise and the Peri," which was sometime since exhibited at the gallery of the Western Arts Association, and greatly admired by those of our citizens who had an opportunity of viewing it. Mr. Duncanson visited Europe several times and found sale for his works there through the efforts of Miss Charlotte Cushman, some of the pictures being purchased by the Duchess of Sutherland. He was an artist of rare accomplishments, and his death will be regretted by all lovers of his profression, and by every American who know him either by reputation or personally. 27

Duncanson mastered the most universally accepted style of painting in the Western World during his lifetime of combining a form of romantic realism with a poetic yet mysteriously expressive kind of subject matter, which showed a love and reverance of nature beyond that which had been sanctioned by members of the Hudson River School. He left behind a path of competency in his pursuit of art that has been unmatched by many artists who were to follow him. His development as an artist of versitile skills is recorded in the visual portraual he gave through the art of portraiture, the decorative murals at The Taft Museum, and the many romantic views he recorded of the topographical studies of nature in various parts of the Western world. His artistry marks the "coming of the age" of black artist in America whose previous plight as service artisan was now lifted to the height of a new kind of aesthetic expression which was destined to gain deserving respect in the years ahead. The work of Robert S. Duncanson is being singled out by this writer to reveal in part a limited measure of success which was achieved by an artists of African descent even during the period of transition in this nation when there

27 Detriot Tribune, December 26, 1872.

MS01.01.03.B02.F10.034

30

was still bladent denial of the rights of Black Americans through democratic principles that were guaranteed every man and woman, regardless of race or creed, by the Constitution of the United States. That Duncanson was able to presevere and rise beyond the level of the ordinary through the exercise of a superior talent in the art of painting during this cruical period in history attests not only his skill at rendering and defining with the eye of the poet the lyricism of form so often sought in nature by artists of all culture, but also brings to our attention the majestic drama that he was able to engage in by acting in art upon those ideals which are universal in the lives of men even in a society where racisial prejudice was rampant and openly sanctioned as the law of the land. In a sense, Duncanson's work represents without question the highest level of achievement in American art that was obtainable in his day. The Black artist, even during the period of turbulance and strife, in the 19th century, which was brought on by the ongoing system of human slavery in America, never lost sight of his goals of achieving a lofty position in the art world as a practitioneer who would be respected first al all for the mastery of his craft. He neither wanted nor condoned his being set aside in a specific sociological catergory which was based primarily on race. But realizing the nature of the racially conscious world in which he had been born, he had to struggle against insurmountable odds to maintain his humanity and spiritual devotion to art. But art in America, like all other forms of cultural expression, is seldom so ordered as to fit into one disinct catergory whereby one prevailing style of modern of expressing content is acceptable to all practitioners who consider themselves makers of visual form. In this sense, the black artist is no different from any other in that he too must struggle to stisfy the natural eurge within to be sensitive to order and form through media and at the same time feel the temporal order of his existence in relation to the socio-cultural patterns of his enviorment.

MS01.01.03.B02.F10.035

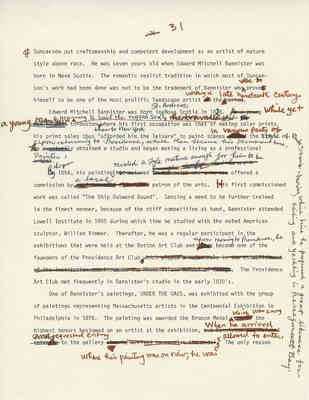

Duncanson put craftsmanship and competent development as an artist of mature style above race. He was seven years old when Edward Mitchell Bannister was born in Nova Scotia. The romantic realist tradition in which most of Duncanson's work had been done was not to be the trademark of Bannister who was to prove himself to be one of the most prolific landscape artist working in the later twentieth century.

Edward Mitchell Bannister was born in Saint Andrews Nova Scotia in 1828. While yet a young man with a yearning to sail the rugged sea to Boston then to New York, where his first occupation was that of making solar prints.

His print sales this "affored him the leisure" to pain scenes in various parts of the style of Rhode Island, during which time he proposed a great likeness for sailing and yachting in narragamsett Bay. Upon returing to Providence, whcih then became his permanent hom, obtained a studio and began making a living as a professional painter.

By the year 1854, his painting revealed a style mature enough for him to be offered a commission by a local patron of the arts. His first commissoned work was call "The Ship Outward Bound". Sensing a need to be further trained in the finest manner, because of the stiff competition at hand, Bannister attended Lowell Institute in 1855 during which time he studied with the noted American sculptor, William Rimmer. Thereafter, he was a regular participant in the exhibitions that were held at the Boston Art Club and upon moving to Providence, he became one of the founders of the Providence Art Club. The Providence Art Club met frequently in Bannister's studio in the early 1870's.

One of Bannister's paintings, UNDER THE OAKS, was exhibited with the group of paintings representing Massachusetts artists in the Centennial Exhibition in Philadelphia in 1876. The painting was awarded the Bronze Medal which who among the highest honors bestowed on an artist at the exhibition, when he arrived and requested entry to the gallery where his painting was on view, he was not allowed to enter. The only reason