Description

Related Subjects

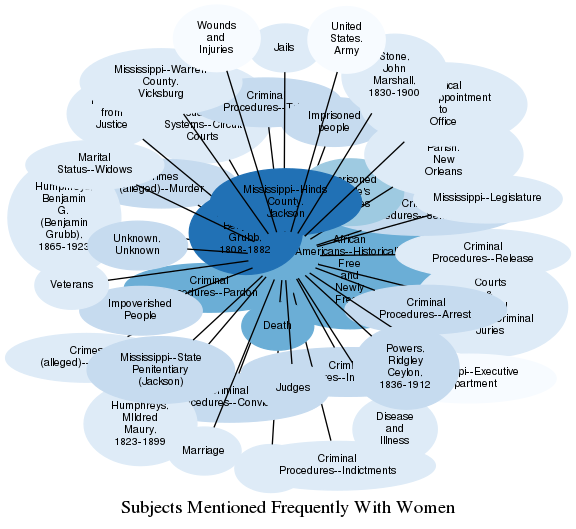

The graph displays the other subjects mentioned on the same pages as the subject "Women". If the same subject occurs on a page with "Women" more than once, it appears closer to "Women" on the graph, and is colored in a darker shade. The closer a subject is to the center, the more "related" the subjects are.