Description

While the Cambridge Dictionary defines marriage as “a legally accepted relationship between two people in which they live together, or the official ceremony,” CWRGM employs this subject tag whenever an author references marriage regardless of whether it was legally binding or not.

See also: https://dictionary.cambridge.org/us/dictionary/english/marriage

Related Subjects

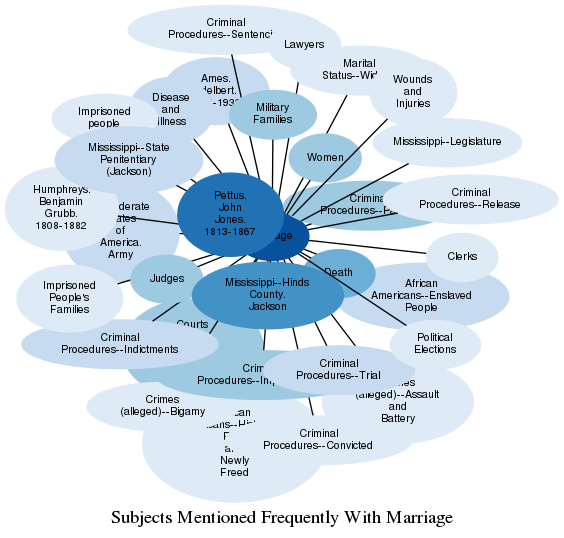

The graph displays the other subjects mentioned on the same pages as the subject "Marriage". If the same subject occurs on a page with "Marriage" more than once, it appears closer to "Marriage" on the graph, and is colored in a darker shade. The closer a subject is to the center, the more "related" the subjects are.