Pages That Mention Columbia

Coast Guard District narrative histories 1945

44

One of the most remarkable advances in inland marine navigation was that which tranferred the swirling waters of the Columbia river into 300 miles of navigable waterway. In 1805, when Lewis and Clark concluded their amazing trek to the Northwest Coast, vast portions of the Columbia River defied the explorers' attempts to transport their party and supplies on its broad expanse. Almost 140 years later, great ocean-going vessels were able to ply their way into Oregon and Washington river ports.

The wildness of the river lay in the swiftness of the water forming treacherous whirlpools and rapids over the shallow, jagged bottom. To eliminate this danger, two great projects were undertaken: The Bonneville Dam and the Celilo Canal. Although the canal was finished before World War I, river traffic to The Dalles, Oregon, and beyond, had ceased around 1916. In 1932, navigation in this section was revived for the transportation of wheat, but the service between the Upper and Lower ports was intermittent. This renewal of navigation was more or less on a trial basis to determine if sufficient commerce could be developed to support water carrier operation.

Sufficient traffic was realized and, after the construction of the Bonneville Dam which was completed in 1938, river traffic expanded into the movement of great steel barges designed to carry liquid petroleum in the hull and package or bulk cargo on deck. With this increase of traffic from Astoria, Oregon, beyond The Dalles, Oregon, the necessity of navigational aids to insure the mariner's safety became most apparent. As a result, the Seattle District centered the majority of its activities in the promotion of safe navigation along the river. Here was the proving grounds for experimental light structures and buoys to determine those most suitable for the area. Due to the rapid current, ranges marking channels had to be so perfected as to enable the mariners to ascertain his course in split-second timing.

The sheer steep cliffs of this area presented problems in erecting shore structures and the swift waters made the mooring of buoys almost impossible. Even before the consolidation of the Lighthouse Service and the Coast Guard, the problems of marking the river had been of primary importance to the Lighthouse Service and basic markings had been established along the banks. The last allotment made to the Service in 1939 was for the establishment of additional lights in the Columbia, Umpqua and Yaquina Bay. River traffic

-25-

45

at that time consisted mainly of the transportation of oil to inland ports and the movement of wheat downstream. Although the water was proven open to ocean-going vessels, the majority of the craft were tugboats and freight barges, especially the section above Celilo, Oregon. Several "oil tank farms" had been established along the shore to supply Army and Navy installations in that area and it was from these "farms" that the vast supply of oil and fuel came, so necessary in the Dupont project at Hanford, one of the plants that specialized in the manifacture of the Atomic Bomb. War gave emphasis to the river traffic and, subsequently, the Atomic Bomb. War gave emphasis to the river traffic and, subsequently, the Aids to Navigation Section of the Seattle District concentrated on lessening the danger and increasing the safety of those who plied the columbia.

53

Tests of the channel limiting group equipment were observed by the District Engineering and Marine Inspection Officers and it was their recommendation that it was worthwhile to establish and to put into use such an experimental range on the Columbia River. This was done at Arlington, Oregon, with Headquarters' approval, in the Spring of 1945. An investigation of the success of this type of range indicated that the majority of the operators preferred the old type regular center line lighted range of two boards. This preference, in the opinion of the District Coast Guard Office, was made primarily because of the lack of understanding and the use of the limiting channel range and, consequently, detailed printed instructions were issued to all operators in the Celilo-Pasco District where the Arlington range was located. As a result, more favorable comments were received in regard to the use of the limiting channel lights, but, notwithstanding, Headquarters would not authorize their establishment on other ranges where the two-board range was impracticable because of the terrain. This policy, which Headquarters adopted, left areas in the Columbia River unsafe for navigation as the lights and markings which could be established there provided only inadequate coverage.

INCREASE OF AIDS AND CHANNEL IMPROVEMENTS

Recommendations for the increase of aids to insure safety of mariners in the Upper Columbia were presented to the District Coast Guard Officer and Headquarters by the Board of Survey. Headquarters felt that complete justification for the project as a whole, as being vital to the war effort, had not been furnished, and requested that a complete list of all shipping interests concerned, the extent of their operations, and a list of all government agencies involved there in the war interest, be furnished. Letters from navigation companies indicating the large burdens placed on water carriers to transport the required petroleum products to Army and Navy installations on the Columbia were forwarded to Headquarters together with freight tonnages and traffic statistics. The proposed improvements were then approved and an appropriation of $50,000 was granted. (June, 1940). Additional appropriations were granted later.

The Snake River, which enters the Columbia just south of Pasco, Washington, was not navigable except during high water from the middle of March to the middle of July. At the time of the survey, the U. S. Army Engineers were contemplating the improvement of the Snake River by providing a

-33-

54

channel five feet deep from the mouth of the Snake to Lewiston, Idaho, 139 miles upstream. However, this portion of the river presented additional problems in that the rise in elevation to Lewiston from the mouth was 400 feet and the waters swift and shallow. Army Engineers had surveyed this section in 1934 at a cost of $150,000.00 but by 1940 the survey marks were missing and existing maps of the river were unreliable. Althought railway lines paralleled the Snake River on either side to Lewiston, most of the shipping in the area was done by barge as the freight charges for rail transportation was excessive. In anticipation of the Army's proposed dredging, wheat elevators had been constructed along the banks of the Snake, in spite of the fact that river traffic had been discontinued for some time prior to the Army's proposed project. Improvement of the Snake River was calculated to reduce the price of waterborne gasoline about 1 cent at Lewiston and 3/4 cent at Spokane and to insure navigation at least nine months of the year. On the strength of the Army's proposal, Headquarters allotted $33,000.00 for the establishment of aids along the Snake to Lewiston but this was later diverted to other projects as so little progress was made by the Army in the dredging of the proposed channel by 1945.

Ranges were not established even though there was a minimum of river traffic near Lewiston as the Board felt that the establishment of any aids implied responsibility for the safety of the courses over which soundings and chart data were incompleted. By the end of World War II, river traffic on the Columbia had reached a peak. Day and night, winter and summer, through fog or clear weather, tugs and barges, fishing boats and other commercial marine craft plied the river from Astoria, Oregon to Pasco, Washington. The Upper Columbia had been thoroughly marked with additional aids to insure safe navigation; Army Engineers had dredged channels to promote commerce; and inland navigation companies had increased their tonnage so that by 1945 the Columbia River had taken its place amongst the top ranking commercial waterways of the world. But, at Pasco, extensive river traffic ceased for beyond this point the conditions of the river made through traffic impossible. Although the Columbia reached for hundreds of miles beyond Pasco, Washington, all commerce was localized in small areas along its length.

AIDS IN ROOSEVELT LAKE

The building of the Grand Coulee Dam on the far reaches of the Columbia, to provide water for irrigation and water power for this great Northwest section, brought about additional activities for the Aids to Navigation Section. The building of the dam created a lake which extended almost 200

-34-

57

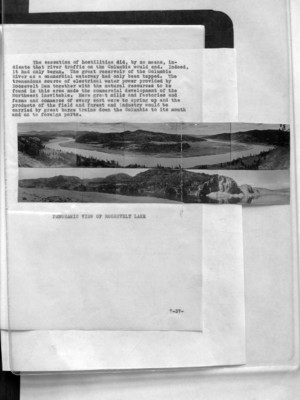

The cessation of hostilities did, by no means, indicate that river traffic on the Columbia would end. Indeed, it had only begun. The great reservoir of the Columbia River as a commercial waterway had only been tapped. The tremendous source of electrical water power provided by Roosevelt Dam together with the natural resources to be found in this area made the commercial development of the Northwest inevitable. Here great mills and factories and farms and commerce of every sort were to spring up and the products of the field and forest and industry would be carried by great barge trains down the Columbia to its mouth and on to foreign ports.

(image) PANORAMIC VIEW OF ROOSEVELT LAKE

-37-