Pages

26

Logic 26 on the light of nature.

reason called the "light of nature" to distinguish it from the "light of grace" which comes by revelatio, has been the opinion entertained by the majority of careful logicians.

The phrase "light of reason", or itd near equivalent, may probably be found in every literature. The 'old philosopher' of china, Lao-Tze, who lived in the VI century B.C, says for example, "Where useth reason's light, and turneth back, and goeth home to its enlightenment, surrendered not him persons perdition. This is called practising the eternal." The doctrine of a light of reason seems to be inwrapped in the old Babylonian philosophy of the first chapter of Genesis, where the Godhead says, "Let us make man in our image, after our likeness." It may, no

Lao-Tse's Tao-Teh-King. By Paul.Carns. Chicago: 1898. Chapter lii 33.

27

Logic 27 Fallibility of the natural light.

doubt justly be said that this is only an explanaton to account for the resemblances of the images of the gods to men, a difficulty which the Second Commandment meets in another way. But does not this remark simply carry the doctrine back to the days when the gods were not made in men's image? To believe in a god at all, is not that to believe that man's reason is alied to the originating principle of the universe?

The reasonings of the present treatise with I expect make it that the history of science, as well as other facts, pose that there is a actual light of reason, that is that man's guesses at the courts of nature are more often correct than could be otherwise accounted for, while the same facts equally prove that this light is extremely uncertain and deceptive, and consequently unfit to strengthen the principle of logic in any sensible degree.

But the Aristolelians, who compose the majority of

28

Logic 25 Aristotles question

the more minute logicians, appealed directly to the light of reason or to self-evidence as the support of the principles of logic. Grote and other empiricists think that they have proved that Aristotle did not do this, inasmuch as he considered the first principles to owe their origin to induction from sensible experiences. No doubt, Aristotle did hols that to be the case, and held resonably that the general in the particular was directly percieved, an extraordinarily crude opinion. But that process of induction by which he held that first principles became known was according to Aristotle not to be recovered and [ori?ed]. It was not even voluntary. Consequently if Aristotle had been asked how he knew that the same proposition could not be at once true and false he could have given no other proof of it than its self-evidence. Grote and those who agree with him as well as some other schools of thinkers

29

Logic 29

quite overlook the important distinction between thought thst can be controlled and thought which cannot be controlled. It is idle to criticize the later. You cannot criticize what you do not doubt although very many philosophers decieve themselves and others into the belief that they are criticizing what they honestly pretend to doubt and so "argue" for foregone conclusions. A proof or grnuine argument is a mental process which is open to logical criticism. If therefore a philosopher holds that a judgement C has been derived from an antecedent judgement B by a controllable process of thought subject to the minds self-control and that the judgment B has been derived from a still earlier state of mind A by a process of thought not cotrollable he may represent the process by which B has fielded C by a logical form of argument or proof but the other

30

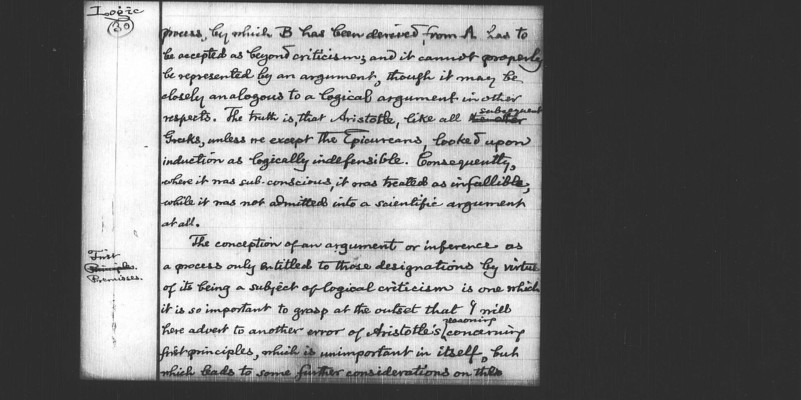

process, by which B has been derived from A has to be accepted as beyond criticism, and it cannot properly be represented by an argument, though it may be closely analagous to a logical argument in other respects. The truth is, that Aristotle, like all the other subsequent Greeks, unless we except the Epicureans, looked upon induction as logically indefensible. Consequently, where it was sub-conscious, it was treated as infallible, while it was not admitted into a scientific argument at all.

The conception of an argument or inference as a process only entitled to those designations by virtue of its being a subject of logical criticism is one which it is so important to grasp at the outset that I will here advert to another error of Aristotle’s reasoning concerning first principles, which is unimportant in itself, but which leads to some further considerations on [these?]