Pages

6

Logic II 6

the classification according to ideas would be the true geneic classificati genuine genealogy. True, the same idea may often twice arises in different times and places, quite independently, as far as history can inform us; so that were we to deem ideas the creations of the persons in whose minds they appear, there would have been oft times agreement in ideas without genetic connection. For we know that the majority of great conceptions have appeared emerged simultaneously in different quarters. But is not this very fact a strong argument to reinforce others which ought to convince us that ideas, or at any rate, not true and great ideas, are not personal creations nor personal property. Far lower is it that the [?] upon the person is conferred the privilege of servitude to the idea. The individual intellect is but the vehicle of the idea; the individual man should be proud to wear its uniform. All that there is of value and permanence in him is the offspring of the idea. The only source of the idea is the form of circumstance in which it was

7

Logic II 7

latent, and from the study of which is would infallibly be drawn. Classification by the abstract forms of facts essentially not connected with objects is classification according to the ideas connected with them. This is the mode in which alone ideas themselves can be classified. Hence, we see find that it is in this way that mathematical forms are always classified. It ultimately comes, as we shall see in due time, to classification according to the cenopythagorean categories, one, two, three. It is evident that classification according to purpose is only a particular form of classification by a connected idea; and so this mode of classification is seen to be sole and supreme. Do not, for a moment, understand me as extolling all numerical classifications, or any considerable percentage of those that are met with; for they are the easiest cheapest and least value worth

8

Logic II 8

able of classifications. Because the true classification, when found, will be found, [?] when it is sufficiently understood, to be in some covert way, numerical, it does not follow that numerical classifications generally are of any particular value.

The habit practice of naturalists, who are, of course, the most exercised in classification of all men, is to give precise definitions of their classes. This may be convenient, but that anything is gained in scientific truth to nature in that way I cannot believe. [ I admit my ignorance of natural history is such that it is rather presumptuous in me to profess any opinion on the subject.] I cannot help thinking that the real classes are separated by causes of divergent modes of growth which causes cannot be observed in themselves. How can it be otherwise? But if this be so, probably not definition based on observable characters of any importance could place the dividing line in the right place; although

9

Logic II 9

if one were to [form?] discriminte the classes by a sort of weighted mean of all the observable characters it would hit right; and even if one were only to do this by estimation, we should probably do better than by risking all upon a single definition. Another singular error which naturalists make quite systematically is to think that the intermediate forms connect two types almost continuously (what they call quite continuously, but that is inaccurate language) those two classes cannot be "founded in nature" but must be purely artificial. There is not only no logical foundation for such an opinion, but it so happens that there is an instance ready at my hand to prove its falsity. Namely if there is any cause in nature tending to produce forms of a certain type, subject to accidental variations, and if from a great number of such forms subject to the same general conditions we plot a curve whose abscissa shall measure any variable character of that type while the ordinates are proportional to the number of instances of each quantity of the variable measured by the abscissa,

10

Logic II 10

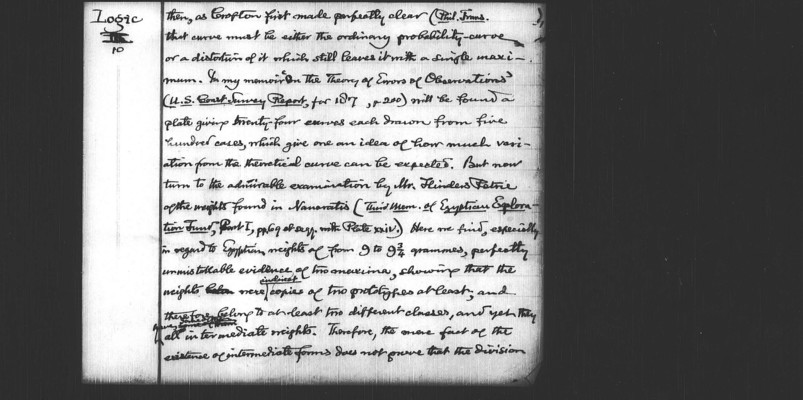

then, as [Compton?] first made perfectly clear (Phil. Trans.). that curve must be either the ordinary probability curve or a distortion of it which still leaves it with a single maximum. In my memoir 'On the Theory of the Errors of Observations' (U.S. Coast Survey Report, for [187?], p.200) will be found a plate giving twenty-four curves each drawn from five hundred cases, which give one an idea of how much variation from the theoretical curve can be expected. But now turn to the admirable examination by Mr. Flinders Petrie of the weights found in Naucratis (Third Mem. of Egyptian Exploration Fund, Book I, pp. 69 of seqq. with Plate xxiv.) Here we find, especially in regard to Egyptian weights of from 9 to 9 3/4 grammes, perfectly unmistakable evidence of two maxima, showing that the weights [have?] were indirect copies of two prototypes at least, and therefore beflong to at least two different classes, and yet they have some [other?] all intermediate weights. Thereforce, the mere fact of the existence of intermediate forms does not prove that the division