Pages

6

in such a state of things, a certain other similarly definite state of things, equally a matter of the imagination, could or could not, in the assumed range of possibility, ever e̶x̶i̶s̶t̶ occur, would be one in response to which one of the two answers Yes and No would be true, but never both. But all pertinent facts would be within the [book?] and call of the imagination; and consequently nothing but the operation of thought would be necessary to render the true answer. Nor [^?] supposing the answer to cover the whole range of possibility assumed, could this be rendered otherwise than by reasoning w̶h̶i̶c̶h̶ that would be apodictic, general, and exact. O̶n̶ ̶t̶h̶e̶ o̶t̶h̶e̶r̶ ̶h̶a̶n̶d̶,.B̶u̶t̶ No knowledge of what actually is, no positive knowledge, as we say, would result. On the other hand, to assert that any source of information that is restricted to actual facts could afford us a̶n̶ a necessary knowledge, that is, knowledge relative to a whole, general range of possibility, would be a flat contradiction in terms

7

T̶h̶e̶r̶e̶ ̶c̶a̶n̶ ̶b̶e̶ ̶n̶o̶ ̶a̶p̶o̶d̶i̶c̶t̶i̶c̶ ̶c̶e̶r̶t̶a̶i̶n̶t̶y̶ ̶a̶b̶o̶u̶t̶ ̶t̶h̶e̶ ̶a̶c̶t̶u̶a̶l̶

Mathermatics is the study of what is true of hypotherical states of things. That is its essence and definition. Everything in it, therefore, beyond the f̶i̶r̶s̶t̶ ̶d̶e̶s̶c̶r̶i̶p̶t̶i̶o̶n̶s̶ first precepts for the construction of the hypotheses, has to be of the nature of doubt, apodictic c̶o̶n̶c̶l̶u̶s̶i̶o̶n̶ inference. No doubt we may reason imperfectly and jump at a conclusion: still, the conclusion so guessed at is, after all, that in a certain supposed state of things something would necessarily be true. Conversely too, every apodictic inference is, strictly speaking, mathematics. But mathematics, as a serious science, has over and above its essential character of being hypotherical, an accidental characteristic [peculiarity?] a proprium, as the Aristotelians used today, - which is of the greatest logical interest. Namely, while as the "philosophers," follow Aristotle in holding [?] demonstration to be thoroughly satis-

8

factory except what they call a "direct" demonstration, or a "demonstration why", - by which they mean a demonstration which employs only general concepts and concludes nothing but what would be an item of a definition if all its terms were f̶u̶l̶l̶y̶ distinctly defined themselves, the mathematicians, on the contrary, entertain a contempt for that style of reasoning, and glory in what the philosophers stigmatize as "mere" indirect demonstrations, or "demonstrations that". Those propositions which can be deduced from others by reasoning of the kind that the philosophers extol are set down by mathematicians as "corollaries". That is to say, they are like these geometrical truths which Euclid did not deem worthy of particular mention, and which his editions inserted with a garland, or corolla, against each in the margin, implying perhaps that it was then that such humor might attach to these insignificant

9

remarks was due. In the theorems, or at least in all the major theorems, a different kind of reasoning is demanded. Here, it will not do to confine oneself to general terms. It is necessary to set down, or to imagine, some individual and definite schema, or diagram; - in geometry, a figure composed of lines with letters attached; in algebra an array of letters of which some are repeated. This schema is constructed so as to conform to a hypothesis set forth in general terms in the thesis of the theorem. Pains are taken so to construct it that there would lie something closely similar in every possible state of things to which the hypothetical description in the thesis would be applicable, and further more to construct it so that it shall have no other characters which could influence the reasoning. How it can be that, although the reasoning is based upon the study of an individual schema, it is neverthe

10

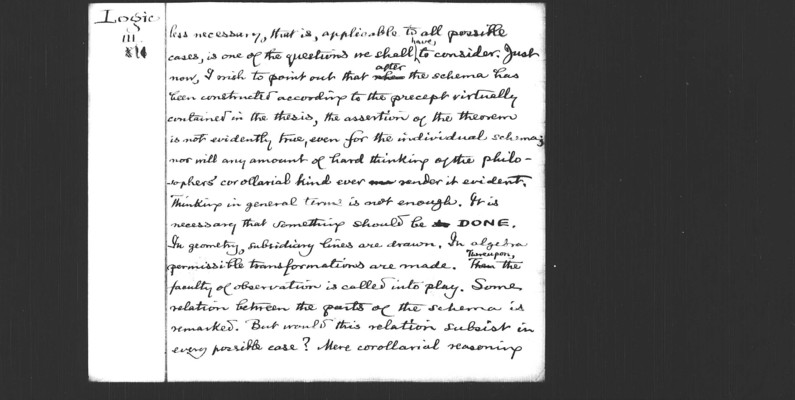

less necessary, that is, applicable to all possible cases, is one of the questions we shall have to consider. Just now, I wish to point out that after the schema has been constructed according to the precept virtually contained in the thesis, the assertion of the theorem is not evidently true, even for the individual schema; nor will any amount of hard thinking of the philosophers' corollarial kind ever render it evident. Thinking in general terms is not enough. It is necessary that something should be DONE. In geometry, subsidiary lines are drawn. In algebra permissible transformations are made. Thereupon, the faculty of obseervation is called into play. Some relation between the parts of the schema is remarked. But would this relation subsist in every possible case? Mere corollarial reasoning