Pages

112

I have now said all I need say about rationals. It is plain that in order to consider analytic continuity I must take up irrationals. I shall not need to consider any other ordinal. In order to consider true continuity I must consider the doctrine of multitude; and it will be more convenient to consider multitude first and irrationals afterward.

But at the very threshold of multitude, I am met by a great logical difficulty. For the whole doctrine of Multitude is founded upon a conception of the relation of one collection's being greater than another which is by no means the common-sense idea of that relation and which was first given to the world by Bernard Bolzano, who was at once a logician and a catholic theologian, a combination of specialties pretty sure to lead to grave personal inconvenience,

113

as it did in his case and has done in most cases where the logician has attempted to advance his science. The common sense idea of being greater than is that if one collection contains a member representative of every member of another collection and more beside, it is greater than that other; and consequently an infinite collection is greater than itself. But Bolzano's definition does not allow any collection to be greater than itself, if there are two collections the As and the Bs and if there is any possible relation, r, in which every A stands to a B to which no other A is r, then, says Bolzano, we will say that the collection of As is not greater than that of the Bs. If there be no possible relation of that sort the collection of As is greater than that of the Bs. But, thereupon, there at once

114

arises the question, why may not two collections each be greater than the other? To this an obvious reply is that if nothing at all be considered as a collection, as a mathematician would naturally consider it, that collection is greater than itself. Now if that be possible, the idea of magnitude breaks down. There are logico-mathematicians who think it is possible.

But there are others, Cantor among them, who think not. To me the notion that every one-to-one relation between As and Bs should leave over some As unrelated to any Bs although there are B to which no As are related, and that there should be no relation whatever in which these unoccupied As could stand to those unoccupied Bs is contrary to the nature

115

of relation and of possibility.

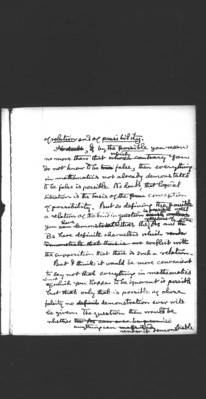

If by the possible you mean no more than that which you do not know to be false, then everything in mathematics not already demonstrated to be false is possible. No doubt, that logical situation is the basis of the conception of possibility. But so definin,g the possible a relation of the kind in question is possible until you have demonstrated that the collections of As and of the Bs have definite characters which conflict with the supposition that there is such a relation.

But I think it would be more convenient to say not that everything in mathematics about which you happen to be ignorant is possible but that only that is possible of whose falsity no definite demonstration ever will be given. The question then would be whether anything can render it demonstrable