Pages

31

G32

construction or an algebraical formula or array of signs. The denotation of icons is essentially indefinite. Most deductions require besides signs which term icons indices, that is signs which deno represent their objects by being notably (though it may be virtue of being connected with them in fact, although this fact be but the actual occurrence of a thought. only in the imagination) attached to connected with them in fact Such are the letters attached to a geometrical diagram, and the subjacent numbers often attached to letters in algebra to show to what objects they refer; as when x1, y1, z1, x2, y2, z3 denote the three coordinates of two different points. The denotation of an index is essentially singular, since actual facts are singulars. Many deductions cannot be performed, even in the mind, without the use

32

G33

of signs of a third kind, which I term symbols; that is to say, signs which represent their objects simply because they will be so understood, or arbitrary signs. Such are all words, not even, I think, excepting perhaps proper names, where the distinction between an a symbol and an index becomes almost too fine to be drawn with certainty. Unless by the name be meant certain lines on a certain individual piece of paper, or the single event of an a single utterance, the name is a thought, and strictly is a general concept although a very narrow one. Nor is it in fact connected with the real man, but is only connected in thought with the thought of the man; and it stands for the real man only

33

G34

because it is thought to do so. It thus seems to me to be clearly a symbol. The denotation of a symbol is always definitely general; that is it stands for any object its interpreter may choose, provided it be of a certain description, and not merely for some unspecified object of that description which its utterer may have in mind.

The deductive reasoner, knowing already pretty nearly what it is that he proposes to prove, makes an icon of the conditions of the problem, and attentively considers it. There are two kinds of deduction, th which I term for which no better designations have occurred to me than the logistic and the logical

34

G35

syllogical substages of deduction, or definitory and ratiocinative deduction. The former includes the analysis of concepts, the acquisition of distinct ideas, and the transformation of them into fruitful forms. A whole class of demonstrations that have given mathematicians no little trouble, such for example as that discovery of Euler's which forms the 25th proposition of the VIIth book of Legendre's Éléments de géométrie, the sum of the number of faces and summits of an ordinary polyhedron exceeds the number of edges by

35

G36

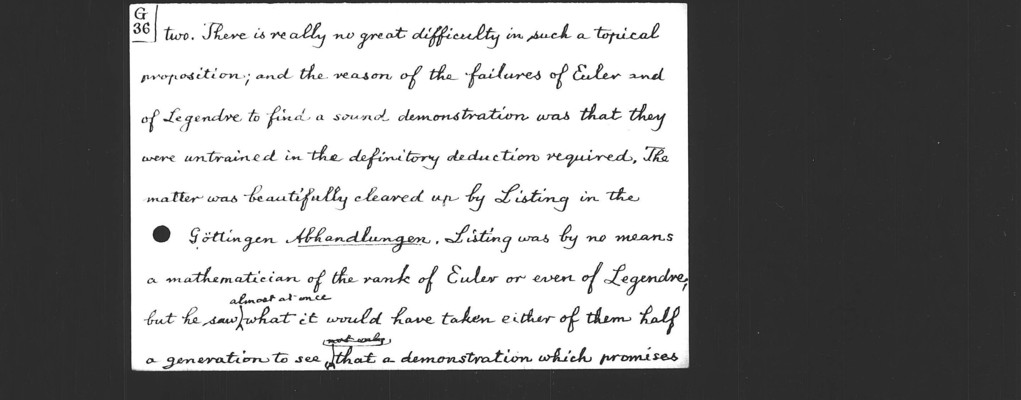

two. There is really no great difficulty in such a topical proposition; and the reason of the failures of Euler and of Legendre to find a sound demonstration was that they were untrained in the definitory deduction required. The matter was beautifully cleared up by Listing in the Göttingen Abhandlungen. Listing was by no means a mathematician of the rank of Euler or even of Legendre, but he saw almost at once what it would have taken either of them half a generation to see, not only that a demonstration which promises