Pages

36

What Was the Impact of Segregation Beyond the Black Community?

In Gong Lum v. Rice, 275 U.S. 78 (1927), the United States Supreme Court held that Martha Lum, a Chinese girl living in Mississippi, had no right to an education in a "whites only" public school if a "colored" public school was available to her.

The Legislature is not compelled to provide separate schools for each of the colored races, and unless and until it does provide such schools, and provide for segregation of the other races, such races are entitled to have the benefit of the colored public schools. . . . If the plaintiff desires, she may attend the colored public schools of her district, or, if she does not desire, she may go to a private school. . . . But plaintiff is not entitled to attend a white public school. -- Excerpt from the Mississippi Supreme Court decision upheld in Gong Lum v. Rice

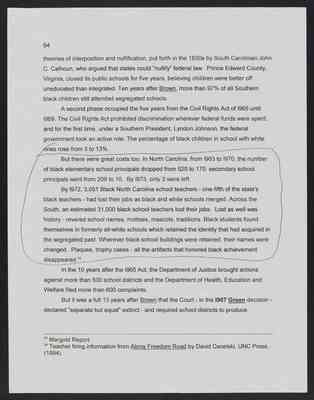

[image:] Photograph of a woman pointing to a large sign hanging above the porch of a home. The sign reads: "JAPS KEEP MOVING THIS IS A WHITE MANS NEIGHBORHOOD." In addition, there is a partially-obscured sign on the left that reads "JAPS KEEP OUT YOU ARE NOT WANTED" Caption: Hollywood, Los Angeles, California, 1923 © Bettmann/CORBIS; reprinted with permission

Focus Questions

1. Many groups in America have faced discrimination for their racial, ethnic, or religious identities. What is the difference between discrimination by private individuals or organizations and segregation enforced by law?

2. Suppose that the education offered at the "colored school" nearest Martha Lum's home had been equal to that offered at the "whites only" school in terms of quantifiable factors (books, physical facilities, teachers, etc.). What harm would Martha Lum have suffered by being denied admission to the "whites only" school?

3. What is the relationship between groups who were subject to official segregation in the years preceding the decision in Brown v. Board and groups who are included in affirmative action policies today? What consequences of segregation are affirmative action policies intended to remedy? When do you think such policies will no longer be necessary?

What Are Acceptable Preferences in College Admissions?

[I]n the national debate on racial discrimination in higher education admissions, much has been made of the fact that elite institutions utilize a so-called "legacy" preference to give the children of alumni an advantage in admissions. . . . The Equal Protection Clause does not, however, prohibit the use of unseemly legacy preferences or many other kinds of arbitrary admissions procedures. What the Equal Protection Clause does prohibit are classifications made on the basis of race. So while legacy preferences can stand under the Constitution, racial discrimination cannot. -- Justice Clarence Thomas, dissenting in Grutter v. Bollinger, No. 02-241 (2003)

Focus Questions

1. Justice Thomas mentions "many other kinds of arbitrary admissions procedures." These include preferences granted to • children of alumni ("legacies") • athletes • students with certain special skills (isncluding musical ability and artistic talent) • students from other parts of the country, and from rural areas Why do you think colleges might favor such students?

2. The majority in this case held that the use of race in admissions decisions was permitted under the Equal Protection Clause where the policy resulted in the kinds of educational benefits that flow from a diverse student body. What other kinds of preferences in admissions decisions could be justified on the same basis?

3. How do you think higher education in America would be different if the legislature enacted laws banning legacy preferences and other kinds of preferences? What could be done to make the higher education admissions process become a true meritocracy?

Dialogue on Brown v. Board of Education

5

37

Who Is Guilty for the Harms of Slavery and Segregation?

The islands from Charleston, south, the abandoned rice fields along the rivers for thirty miles back from the sea, and the country bordering the St. Johns river, Florida, are reserved and set apart for the settlement of the negroes now made free by the acts of war and the proclamation of the President of the United States. -- Special Field Order No. 15, Major General W. T. Sherman, January 15, 1865

General Sherman, a Union commander in the Civil War, further specified that each family settling the area should have a plot of up to forty acres of land and use of a surplus Army horse of mule ("forty acres and a mule").

Congress established the Freedmen's Bureau later in 1865, providing that the Bureau, under direction of the President, had authority to set apart abandoned or confiscated land in the former Confederacy and grant freedmen (former slaves) parcels of up to forty acres.

President Andrew Johnson refused to enforce the provision of the Freedmen's Bureau legislation providing for grants of land to freedmen. Land that had been confiscated from or abandoned by white Southern landowners during the Civil War was returned to them after they took an oath of future loyalty to the Union or were pardoned by President Johnson.

[image:] Cartoon of a man kicking a furniture bureau labeled "freedmen" out of a building labeled "The Veto" with the following caption. Thomas Nast, "Andrew Johnson Kicking Freedmen`s Bureau," Harper's Weekly, April 14, 1866, page 232. Reprinted with permission of HarpWeek,LLC

--

Focus Questions

1. Until the Civil War, slavery was legally permissible in much of the United States. The United States Supreme Court endorsed segregation laws until 1954. Is it justifiable to declare an individual or a society guilty for committing acts that were sanctioned by the government?

2. The United States has paid reparations to Japanese Americans confined to internment camps during the Second World War. Germany has paid reparations to survivors of the Holocaust. Should the descendents of slaves be paid reparations for the harms suffered by their ancestors? What about black Americans living today who suffered the impact of segregation firsthand? To what extent can monetary reparations compensate for past harm?

3. For some Americans, the phrase "forty acres and a mule" represents a promise broken by the United States government. Others note that General Sherman's order applied only during wartime and that President Johnson was never legally compelled to grant the land contemplated in the 1865 Freedmen's Bureau Act. What happens to property confiscated by the winning side in times of war? What do you think should have been done to the land confiscated from individuals who supported the Confederacy in the Civil War?

38

Participating in a Dialogue on Brown v. Board of Education

Once of the hallmarks of a democracy is its citizens' willingness to express, defend, and perhaps reexamine their own opinions, while being respectful of the view of others. As you engage in your dialogue, here are some ground rules for ensuring a civil conversation:

■ Show respect for the views expressed by others, even if you strongly disagree.

■ Be brief in your comments so that all who wish to speak have a chance to express their views.

■ Direct your comments to the group as a whole rather than to any one individual.

■ Don't let disagreements or conflicting views become personal. Name-calling and shouting are not acceptable ways of conversing with others.

■ Let others exress their views without interruption. Your dialogue leader will try to give everyone a chance to speak or respond to someone else's comments.

■ Remember that a frank exchange of views can be fruitful as long as you observe the rules of civil conversation.

Note to Dialogue Leaders: Before beginning your dialogue, distribute these ground rules and review them with students.

--

The ABA Division for Public Education provides national leadership for law-related and civic education efforts in the United States, stimulating public awareness and dialogue about law and its role in society through our programs and resources and by fostering partnerships among bar associations, educational institutions, civic organizations, and others.

A .pdf version of the "Dialogue on Brown v. Board of Education" is available on the ABA Division for Public Education Web site at www.abanet.org/publiced.

The views expressed in this document have not been approved by the House of Delegates or the Board of Governors of the American Bar Association and, accordingly, should not be construed as representing the policy of the American Bar Association.

Design: mc2 communications

Cover photograph by Cass Gilbert, 1954; © Bettmann/CORBIS. Reprinted with permission.

Copyright © 2003 American Bar Association

[image:] Logo for "DIVISION FOR PUBLIC EDUCATION AMERICAN BAR ASSOCIATION"

541 North Fairbanks Court Chicago, IL 60611 (312) 988-5735 Email: abapubed@abanet.org www.abanet.org/publiced

39

Data on African Americans from the Decennial Census

Cf. Brown when enforced

| Number of black | in 1960 | in 1970 | Increase from 1960 | Ratio 1970/1960 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lawyers | 2180 | 3379 | 1199 | 1.6 |

| Doctors | 4706 | 11436 | 6730 | 2.4 |

| Policemen | 9391 | 23796 | 14405 | 2.5 |

| Electricians | 4978 | 14145 | 9167 | 2.8 |

| Bank Tellers | n/a | 10663 | ||

| Architects | 233 | 1258 | 1025 | 5.4 |

| Clergymen | 13955 | 13030 | -925 | 0.9 |

| College Professors | 5415 | 16810 | 11395 | 3.1 |

| Dentists | 1998 | 2098 | 100 | 1.1 |

| Social Workers | 14276 | 33869 | 19593 | 2.4 |

| Carpenters | 3672 | 44529 | 40857 | 12.1 |

| Teachers | 122163 | 223263 | 101100 | 1.8 |

| Social Scientists | 1069 | 3088 | 2019 | 2.9 |

| Pharmicists | 1069 | 3088 | 1039 | 1.7 |

| Nurses | 32034 | 62325 | 30291 | 1.9 |

Source: 1960 Census of Population and 1970 Census of Population Characteristics of Population, United States Summary U.S. Census Bureau

Real wages for black women textile workers in South Carolina

| in 1960 | in 1970 | Increase from 1960 | Ratio 1970/1960 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Average daily real wages | 9.5 | 13.5 | 4 | 1.4 |

40

64

theories of interposition and nullification, put forth in the 1830s by South Carolinian John C. Calhoun, who argued that states could "nullify" federal law. Prince Edward County, Virginia, closed its public schools for five years, believing children were better off uneducated than integrated. Ten years after Brown, more than 97% of all Southern black children still attended segregated schools.

A second phase occupied the five years from the Civil Rights Act of 1965 until 1969. The Civil Rights Act prohibited discrimination wherever federal funds were spent, and for the first time, under a Southern President, Lyndon Johnson, the federal government took an active role. The percentage of black children in school with white ones rose from 3 to 13%.

[Following two paragraphs are circled]

But there were great costs too. In North Carolina, from 1963 to 1970, the number of black elementary school principals dropped from 620 to 170; the secondary school principals went from 209 to 10. By 1973, only 3 were left.

By 1972, 3,051 Black North Carolina school teachers - one-fifth of the state's black teachers - had lost their jobs as black and white schools merged. Across the South, and estimated 31,000 black school teachers lost their jobs. Lost as well was history - revered school names, mottoes, mascots, traditions. Black students found themselves in formerly all-white schools which retained the identity that had acquired in the segregated past. Wherever black school buildings were retained, their names were changed. Plaques, trophy cases - all the artifacts that honored black achievement disappeared.24

In the 10 years after the 1965 Act, the Department of Justrice brought actions against more than 500 school districts and the Department of Health, Education and Welfare filed more than 600 complaints.

But it was a full 13 years after Brown that the Court - in the 1967 Green decision - declared "separate but equal" extinct - and required school districts to produce

--

23 Margold Report.

24 Teacher firing information from Along Freedom Road by David Cecelski, UNC Press, (1994).