Pages That Need Review

Missouri v Jenkins 2 (NOTE)

77

93-1823-dissent

2 MISSOURI v. JENKINS

and argument informed by an appreciation of the potential breadth of the ruling. The deficiencies from which we suffer have led the Court effectively to overrule a unanimous constitutional precedent of 20 years standing, which was not even addressed in argument, was mentioned merely in passing by one of the parties, and discussed by another of them only in a misleading way.

The Court's departures from the practices that produce informed adjudication would call for dissent even in a simple case. but in this one, with a trial history of more than 10 years of litigation, the Court's failure to provide adequate notice of the issue to be decided (or to limit the decision to issues on which certiorari was clearly granted) rules out any confidence that today's result is sound, either in fact or in law.

I

In 1984, 30 years after our decision in Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U. S. 438 (1954), the District Court found that the State of Missouri and the Kansas City, Missouri School District (KCMSD) had failed to reform the segregated scheme of public school education in the KCMSD, previously mandated by the State, which had required black and white children to be taught separately according to race. Jenkins v. Missouri, 593 F. Supp. 1485, 1490-1494, 1503-1505 (WD Mo. 1984). 1 After

[Footnotes] 1 In related litigation about the schools of St. Louis, the Eighth Circuit has noted that "(b)efore the Civil War, Missouri prohibited the creation of schools to teach reading and writing to blacks. Act of Feb. 16, 1847, [?]1, 1847 Mo. Laws 103. State-mandated segregation was first imposed in the 1865 Constitution, Article IX [?]2. It was reincorporated in the Missouri Constitution of 1945: Article IX specifically provided that separate schools were to be maintained for 'white and colored children.' In 1952, the Missouri Supreme Court upheld the constitutionality of Article IX under the United States Constitution. Article IX was not repeealed until 1976." Liddell v.

78

93-1823-DISSENT

MISSOURI v. JENKINS 3

Brown, neither the State nor the KCMSD moved to dismantle this system of separate educaation "root and branch," id., at 1505, despite their affirmative obligation to do that under the Constitution. Green v. School Bd. of New Kent County, 391 U. S. 430, 437-438 (1968). "Instead, the (KCMSD) chose to operate some completely segregated schools and some integrated ones," Jenkins, 593 F. Supp., at 1492, using devices like optional attendance zones and liberal transfer politices to "allo(w) attendance patterns to continue on a segregated basis." Id., at 1494. Consequently, on the 20th anniversary of Brown in 1974, 39 of the 77 schools in the KCMSD had student bodies that were more than 90 percent black, and 80 percent of all black schoolchildren in the KCMSD attended those schools. Id., at 1492-1493. Ten years later, in the 1983-1984 school year, 24 schools remained racially isolated with more than 90 percent black enrollment. Id., at 1493. Because the State and the KCMSD intentionally created this segregated system of education, and subsequently failed to correct it, the District Court concluded that the State and the district had "defaulted in their obligation to uphold the Constitution." Id., at 1505.

Neither the State nor the KCMSD appealed this finding of liability, after which the District Court entered a series of remedial orders aimed at eliminating the vestiges of segregation. Since the District Court found that segregation had caused, among other things, "a system wide reduction in student achievement in the schools of the KCMSD," Jenkins v. Missouri, 639 F. Supp. 19, 24 (WD Mo. 1985) (emphasis in original), it ordered the adoption, starting in 1985, of a series of remedial programs to raise educational performance. As

[Footnotes] Missouri, 731. F. 2d 1294, 1305-1306 (CA8 1984) (case citations and footnote omitted).

79

93-1823-dissent

4 MISSOURI v. JENKINS

the Court recognizes, the District Court acted well within the bounds of its equitable discretion in doing so, ante, at 19, 30; in Milliken v. Bradley, 433 U.S. 267 (1977) (Milliken II), we held that a district court is authorized to remedy all conditions flowing directly from the constitutional violations committed by state or local officials, including the educational deficits that result from a segregated school system (programs aimed to correct those deficits are therefore frequently referred to as Milliken II programs). Id., at 281-283. Nor was there any objection to the District Court's orders from the State and the KCMSD, who agreed that it was "'appropriate to include a number of properly targeted educational programs in (the) desegregation plan,'" Jenkins, 639 F. Supp., at 24 (quoting from the State's desegregation proposal). They endorsed many of the initiatives directed at improving student achievement that the District Court ultimately incorporated into its decree, including those calling for the attainment of AAA status for the KCMSD (a designation, conferred by the State Department of Elementary and Secondary Education upon consideration of a limited number of criteria, indicating "that a school system quantitatively and qualitatively has the resources necessary to provide minimum basic education to its students," id., at 26), full day kindergarten, summer school, tutoring before and after school, early childhood development, and reduction in class sizes. Id., at 24-26

Between 1985 and 1987 the District Court also ordered the implementation of a magnet school concept, 1 App, 131-133 (Order of Nov. 12, 1986), and extensive capital improvements to the schools of the KCMSD. Jenkins v. Missouri, 672 F. Supp. 400, 405-408 (WD Mo. 1987); 1 App. 133-134 (Order of Nov. 12, 1986); Jenkins, 639 F. Supp., at 39-41. The District court found that magnet schools would not only serve to remedy the deficiencies in student achivement in the KCMSD, but

80

93-1823-DISSENT

MISSOURI v. JENKINS 5

would also assist in desegregating the district by attracting white students back into the school system. See, e.g., 1 App. 118 (Order of June 16, 1986) ("(C)ommitment, when coupled with quality planning and sufficient resources can result in the establishment of magnet schools which can attract non-minority enrollment as well as be an integral part of the district-wide improved student achievement"); see also Jenkins v. Missouri, 855 F. 2d 1295, 1301 (CA8 1988) ("The foundation of the plans adopted was the idea that improving the KCMSD as a system would at the same time compensate the blacks for the education they had been denied and attract whites from within and without the KCMSD to formelry black schools").

The District Court, finding that the physical facilities in the KCMSD had "literally rotted," Jenkins, 672 F. Supp., at 411, similarly grounded its orders of capital improvements in the related remedial objects of improving student achievement and desegregating the KCMSD. Jenkins, 639 F. Supp., at 40 ("The improvement of school facilities is an important factor in the overall success of this desegregation plan. Specifically, a school facility which presents safety and health hazards to its students and faculty serves both as an obstacle to education as well as to maintaining and attracting nonminority enrollment. Further, conditions which impede the creation of a good learning climate, such as heating deficiencies and leaking roofs, reduce the effectiveness of the quality education components contained in this plan"); see also Jenkins, 855 F. 2d, at 1305 ("(T)he capital improvements (are) required both to improve the education available to the victims of segregation as well as to attract whites to the schools").

As a final element of its remedy, in 1987 the District Court ordered funding for increases in teachers' salaries as a step towards raising the level of student achievement. "(I)t is essential that the KCMSD have sufficient

81

93-1823-DISSENT

6 MISSOURI v. JENKINS

revenues to fund an operating budget which can provide quality education, including a high quality faculty." Jenkins, 672 F. Supp., at 410. Neither the State nor the KCMSD objected to increases in teachers' salaries as an element of the comprehensive remedy, or to this cost as an item in the desegregation budget.

In 1988, however, the State went to the Eighth Circuit with a broad challenge to the District Court's remedial concept of magnet schools and to its orders of capital improvements (though it did not appeal the salary order), arguing that the District Court had run afoul of Milliken v. Bradley, 418 U. S. 717 (1974) (Milliken I), by ordering an interdistrict remedy for an intradistrict violation. The Eighth Circuit rejected the State's position, Jenkins, 855 F. 2d 1295, and in 1989 the State petitioned for certiorari.

The State's petition presented two questions for review, one challenging the District Court's authority to order a property tax increase to fund its remedial program, the other going to the legitimacy of the magnet school concept at the very foundation of the Court's desegregation plan:

"For a purely intradistrict violation, the courts below have ordered remedies - costing hundreds of millions of dollars-with the stated goals of attracting more non-minority students to the school district and making programs and facilities comparable to those in neighboring districts . . . .

"The questio(n) presented (is) . . . .

". . . Whether a federal court, remedying an intradistrict violation under Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U. S. 483 (1954), may

"a) impose a duty to attract additiional non-minority students to a school district and "b) require improvements to make the district schools comparable to those in surrounding districts." Pet. for Cert. in Missouri v. Jenkins, O. T.

Research Material for Speech- "The Broken Promise of 'Brown v Board of Education' ", 2004

2

THE NEW YORK TIMES, THURSDAY, JANUARY 8, 2004

Surprises in the Family Tree, Black and White

[image:] Paul Heinegg and his family. Attributed to Salvatore D. DiMarco Jr. for The New York Times. With the following text:

BLEND Paul Heinegg, an amateur genealogist, his wife, Rita, center right, and daughters: Ayo, on floor; Asha Armstrong, left; and Andiswa, center.

[image:] Langston family. Attributed to Smithsonian. With the following text:

AMERICANS The "Indian Langstons, above; Susan Ward, below left, and her mother, Susan Mozingo Ward, below right, born 1809, part African-American.

[image:] Photograph of Susan Ward. Attributed to Melicent Remy.

[image:] Photograph of Susan Mozingo Ward. Attributed to Melicent Remy.

Continued From Page 1, This Section

a professor of history at Rice University in Houston and the editor of "The Blackwell Companion to the American South" (2001). Since there was not a clear distinction between slavery and servitude at the time, he said, "biracial camaraderie" often resulted in children. The idea that blacks were property did not harden until around 1715 with the rise of the tobacco economy, by which time there was a small but growing population of free families of color. Dr. Boles estimated that by 1860 there were 250,000 free black or mixed-raced individuals.

"Some academics have studied this parallel story of blacks in America, but it hasn't trickled down to the general population," Dr. Boles said. "The action is in slavery studies." Mr. Heinegg is one of the few people to trace the free black families that lived in slave-owning America: some of them rich slave owners, most of them poor farmers and laborers, nearly all of them little known.

[sidebar:] Uncovering a long history of equality.

"When I saw what Paul had done, my eyes opened wide," said Dr. Ira B. Berlin, a professor of American history at the University of Maryland and the founding director of the Freedmen and SOuthern Society Project there. Dr. Berlin met Mr. Heinegg in November 2000 at a conference in Durham, N.C., about the mixed-race cabinetmaker Thomas Day, a major antebellum figure. The documentation Mr. Heinegg had amassed in five years convinced Dr. Berlin to write a foreword to his book praising his meticulous work.

It is incontrovertible that America is a multiracial society, from the founding father Alexander Hamilton (the son of a mixed-race woman from the British West Indies) to Essie Mae Washington-Williams, 78, a retired schoolteacher, who, the late Senator STrom Thurmond's family acknowledge last month, is his daughter. And for decades there have been questions about the possible mixed-race ancestry of Ida Stover, Dwight D. Eisenhower's mother.

Since 1997, after it broadcast "Secret Daughter," a documentary about a mixed-race child given up for adoption in the 1950's, "Frontline" has been exploring the mixed ancestry of well-known Americans on its Public Broadcasting System Web site. One is AJacqueline Kennedy Onassis, whose blood lines, according to the historian Mario de Valdes y Cocom, go back to the van Salees, a Muslim family of Afro-Dutch origin prominent in Manhattan in the early 1600's. If any branch of your family has been in America since the 17th or 18th centuries, Dr. Berlin said, "It's highly likely you will find an African and an American Indian."

That's where Mr. Heinegg, 60, comes in. In 1985, his mother-in-law, Katherine Kee Phillips, who was black, asked him to research her family tree. "I had hoped to trace as many branches of her family back to slavery as possible," he said. Instead, he found that Mrs. Phillips and his wife, Rita, had white ancestors who were not slave masters, including a woman who started a family with John Kecatan, an African slave freed in 1666. The ladies were intrigued by his discoveries but not surprised, Mr. Heinegg said.

Curious about his findings, he began tracing free black families related to his wife by combing colonial court records, wills, deeds, free Negro registers, marriage bonds and military pension files. Many were dauntingly unindexed.

"Nobody has done anything like this," said Dr. Virginia Easley De-Marce, a historian and former president of the National Genealogical Society who works for teh Office of Federal Acknowledgment, Department of the Interio, which decides who is an American Indian. "Paul is the first person to identify families of color on such a broad scope," gathering material from entire states rather than just a county or two.

Dr. Berlin said, "There were communities in 17th- and 18th-century America where blacks and whites, both free, of equal rank and shared experiences, were working together, living together, drinking and partying together, and inevitably sleeping together."

Tracing those communities has not been easy. "People of color are often not identified as such in early records," Mr. Heinegg said. "For example, an individual might appear in deeds and court records and leave a will without ever mentioning his race." Sometimes a person's race can be discerned only by studying the tax assess on nonwhites. If a man paid the tax on his wife but not himself, Mr. Heinegg said, it meant that he was white but she was not.

An added challenge is that racial identity can mutate from free black to white in just a few generations. In my Archer ancestors' case, it was mixed marriages and a cross-country move: my great-great-grandfather Esquire Collins and his wife, Roxalana Archer, are listed as mulatto in an 1800's Tennessee census but show up as white on a later Arkansas census. "You crossed over as early as you were able to," said Antonia Cottrell Martin, a genealogist in New York. Mixed-race families who had difficulty passing sometimes explained dark complexions as coming from an American Indian or Mediterranean ancestry. "It's what people in the South used to call Carolina Portuguese," said Dr. DeMarce, who comes from a mixed-race background.

"Free African Americans of North Carolina," self-published by Mr. Heinegg in 1991, won an award from the North Carolina Genealogical Society. (The American Society of Genealogist gave a later edition the Donald Lines Jacobus Award for best work of genealogical scholarship.) But the book also stirred controversy. Some white members of the North Carolina group were upset with his findings and asked that the award be withdrawn, Mr. Heinegg said.

Dr. DeMarce said: "He's just publishing the documents. He's not interpeting them. That's up to anthropologists."

Mr. Heinegg is familiar with racial prejudice. He and his wife, who met as members of the Brooklyn outpost of the Congress on Racial Equality, left the country in 1969, disgusted by what they saw as a lack of progress. They raised their three daughters in Tanzania, Liberia and Saudi Arabia.

But even when he was abroad, Mr. Heinegg ordered microfilm records by mail and spent one-month vacations in the United States to peer at faded records in county courthouses. He still works on his research, and updates his book and Web site regularly. A new edition of "Free African Americans" is published every two years by Clearfield, a division of the Genealogical Publishing Company, Inc., www.genealogical.com. The latest two-volume paperback costs $100 and is 1,042 pages long.

The index to Mr. Heinegg's book lists more than 12,000 individuals, including ancestors of mine it would be nice to know more about, like Richard Nickens and his wife, Chriss, freed in 1690 by the will of John Carter II, a prominent Virginia planter. Nickens and his wife were given two cows, six barrels of corn and the right to farm some Carter land for life.

Matters like these fascinate me. My brother, Derrick, finds our black ancestry only mildly interesting, being riveted instead by our Native American blood. My eldest nephew, Justin, an elementary school pupil obsessed with islands, cherishes the knowledge that one ancestors was shipwrecked on Bermuda in 1609.

Genealogy is not regarded as an academic discipline, Dr. DeMarce said, which is why Mr. Heinegg's work is not more widely know. And his lists are published by a specialty house, not a university press, she said, "so it's unlikely to be reviewed by a major publication like The American Historical Review."

Mr. Heinegg prefers to let the academics find his work on their own. Right now, he is busy adding more free black Virginia families to his list. "My goal," he said, "is to find the origins of every family that was free in the Southeast during the colonial period."

18

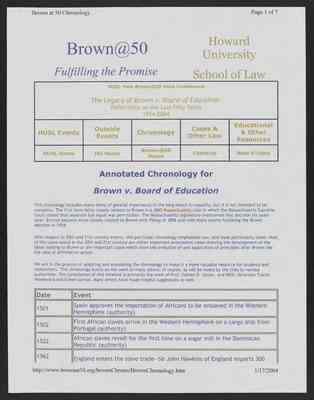

Brown@50 Fulfilling the Promise

Howard University School of Law

HUSL-Yale Brown@50 Joint Conference

The Legacy of Brown v. Board of Education Reflections on the Last Fifty Years 1954-2004

Annotated Chronology for Brown v. Board of Education

This chronology includes many items of general importance in the long march to equality, but it is not intended to be complete. The first item fairly closely related to Brown is a 1849 Massachusetts case in which the Massachusetts Supreme Court stated that separate but equal was permissible. The Massachusetts legislature overturned that decision six years later. Entries become more closely related to Brown with Plessy in 1896 band with many events following the Brown decision in 1954.

With respect to 20th and 21st century events, this particular chronology emphasizes law, and most particularly cases. Most of the cases noted in the 20th and 21st century are either important antecedent cases showing the development of the ideas leading to Brown or are important cases which show the evolution of and application of principles after Brown like the idea of affirmative action.

We are in the process of updating and annotating the chronology to make it a more valuable resource for students and researchers. This chronology builds on the work of many others, of course, as will be noted by the links to various authorities. The compilation of this timeline is primarily the work of Prof. Steven D. Jamar, and HUSL librarians Tracey Woodward and EIleen Santos. Many others have made helpful suggestions as well.

| Date | Event |

|---|---|

| 1501 | Spain approves the importation of Africans to be enslaved in the Western Hemisphere (authority) |

| 1502 | First African slaves arrive in the Western Hemisphere on a cargo ship from Portugal (authority) |

| 1522 | African slaves revolt for the first time on a sugar mill in the Dominican Republic (authority) |

| 1562 | England enters the slave trade -- Sir John Hawkins of Engladn imports 300 slaves to Brazil (authority) |

19

| Date | Event |

|---|---|

| 1619 | Twenty slaves arrive in Jamestown, Virginia, making them the first slaves to arrive in North America (authority) |

| 1638 | First African slaves brought for sale in British Colonies |

| 1704 | Abda, a slave whose mother was a slave and whose father was white, sues his owner, Thomas Richards, pleading that he has been unlawfully enslaved due to his white heritage. Abda loses the case on appeal and is re-enslaved and sent back to Thomas Richards. (authority) |

| 1776 | U.S. Declaration of Independence. Section condemning slavery (authored by Virginia slave owner Thomas Jefferson) is dropped at the insistence of George and South Carolina. (authority) |

| 1777 | Vermont Constitution bans slavery (authority) |

| 1783 | U.S. Peace Treaty with England granting independence to the U.S. (Treat of Paris) (authority) |

| 1787 | Northwest Ordinance art. 6 abolishes slavery in the Northwest Territories |

| 1789 | U.S. Constitution 3/5's compromise (Const. art. I §2) and Fugitive Slave Act (Const. art. IV §2) |

| 1791 | Bill of Rights ratified |

| 1793 | Fugitive Slave Act adopted to enforce Constitutional provision |

| 1808 | Importation of slaves banned U.S. Constitution art. I §9, clause 1; art. 5 |

| 1843 | Prigg v. Pennsylvania 41 U.S. (16 Pet.) 539 (1842): Supreme Court declares unconstitutional a Pennsylvania statute intended to prevent slave owners from using self-help to return fugitive slaves. |

| 1849 | Roberts v. City of Boston, 59 Mass. 198 (1849): Massachusetts Supreme Court declares separate black and white schools legal |

| 1850 | Compromise of 1850 strengthens 1793 Fugitive Slave Act |

| 1855 | Massachusetts overturns effect of Roberts v. City of Boston 59 Mass. 198 (1949) by abolishing segregated schools legislatively |

| 1857 | Dred Scott v. Sanford 60 U.S. (19 How.) 393 (1857) |

| 1861-1865 | Civil War |

| 1/1/1863 | Emancipation Proclamation takes effect |

| 1865 | Civil War Ends |

| 1865 | Black Codes enacted across South to keep African Americans in peonage |

| 12/6/1865 | 13th Amendment Ratified (banning slavery) |

| 1866 | Civil Rights Act provides federal guarantee of rights to contract, to own property, and to sue |

| 1867 | Howard University Founded |

20

| Date | Event |

|---|---|

| 1866-67 | KKK founded in Nashville Tennessee |

| 7/9/1868 | 14th Amendment Ratified (requiring states to grant equal protection) |

| 1869 | Howard University school of Law founded |

| 1870 | 15th Amendment Ratified (voting) |

| 1873 | Slaughter House Cases, 83 U.S. (16 Wall.) 36 (1873): Supreme Court limits the scope of federal power and reach of 14th Amendment to protect rights of citizens of U.S. against states |

| 1875 | Civil Rights Act of 1875 |

| 1877 | End of Reconstruction |

| 1880 | Strauder v. West Virginia, 100 U.S. 303 (1880): Supreme Court holds that states are prohibited from excluding blacks from juries by the Fourteenth Amendment |

| 1883 | Civil Rights Cases, 109 U.S. 3 (1883): Supreme Court holds unconstitutional the Civil Rights Act of 1875 and holds that the 14th Amendment does not prohibit discrimination by private persons |

| 1887 | Florida passes law requiring segregation; Jim Crow laws follow throughout the South |

| 1890 | Louisiana passes a Jim Crow law mandating separate but equal accommodations on railroads for black and white |

| 1890-1920 | Between 1889 and 1918, 3,224 people, predominantly African Americans, are murdered by lynching |

| 1896 | Plessy v. Ferguson, 163 U.S. 537 (1896): upholds separate but equal law of Louisiana |

| 1899 | Cumming v. Richmond County Board of Education, 175 U.S. 528 (1899): public school education is a matter for state regulation, not federal government; local school district can close black school while keeping two white schools open on fiscal grounds |

| 1903 | Giles v. Harris, 189 U.S. 475 (1903): Supreme Court permits black disnefranchisement through state voter registration regulations |

| 1908 | Berea College v. Kentucky, 211 U.S. 45 (1908): Supreme Court rules that private schools are bound by state segregation laws |

| 1909 | NAACP Founded |

| 1917 | Buchanan v. Warley, 245 U.S. 60 (1917): state-mandated residential segregation violates 14th Amendment |

| 1920 | KKK revives |

| 1927 | Gong Lum v. Rice, 275 U.S. 78 (1927): states can define racial classifications for schools; separate but equal logic used |

| 1934 | Charles Hamilton Houson becomes special counsel to the NAACP |

21

| Date | Event |

|---|---|

| 1936 | Pearson v. Murray, 182 A. 590 (Md. 1936): Maryland Court of Appeals holds that University of Maryland law school must grant admission to African Americans (Charles Hamilton Houston and Thurgood Marshall win the case against school that had refused admission to Marshall) |

| 1938 | Missouri ex rel Gaines v. Canada, 305 U.S. 337 (1938): Missouri must offer African-Americans substantially equal legal education which in effect requires admission to Missouri's all white law school |

| 1940 | NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund established under leadership of Thurgood Marshall |

| 1941 | Executive Order 8802, Pres. Roosevelt bars segregation by defense contractors |

| 1948 | Sipuel v. Board of Regents of Oklahoma, 332 U.S. 631 (1948): State law schools cannot discriminate against African Americans |

| 1948 | Shelley v. Kramer, 334 U.S. 1 (1948): Racial restrictive covenants in private housing violate the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment. |

| 1948 | Perez v. Lippod (aka Perez v. Sharp), 32 Cal. 2d 711, 198 P.2d 17 (1948): California's ban on interracial marriage violates the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment. |

| 1948 | United Nations adopts the Universal Declaration of Human Rights |

| 1950 | McLaurin v. Oklahoma State Regents, 339 U.S. 637 (1950); Student in graduate school of education must be treated equally; cannot have separate assigned seating in classrooms, library, etc. |

| 1950 | Sweatt v. Painter, 339 U.S. 629 (1950): Legal education cannot be separate and equal so African American must be admitted to University of Texas law school; the separate law school was not equal |

| 1954 | Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U.S. 483 (1954) (Brown I): Plessy overturned; separate-but-equal violates the 14th Amendment guarantee of Equal Protection |

| 1951 | Brown b. Board of Education, case decided in lower court in Arkansas which became the lead case in the four cases consolidated for appeal in Brown I |

| 1952 | Briggs v. Elliot, South Carolina case, one of the four cases consolidated for appeal in Brown I |

| 1952 | Davis v. County School Board or Prince Edward County Virginia, Virginia case, one of the four cases consolidated for appeal in Brown I |

| 1952 | Gebhart v. Belton, Delaware case, one of the four cases consolidated for appeal in Brown I |

| 1954 | Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U.S. 483 (1954)(Brown I): Plessy overturned; separate-but-equal violates the 14th Amendment guarantee of Equal Protection |