Pages

6

consequences of his assumptions in the readiest and speediest way. The logician does not care much what the conclusions from this or that system of assumptions may be. What he is interested in is in dissecting the mathema tician's reasonings, in finding out what their elementary steps are, and in showing what positive facts about the real universe of things and of thoughts it is from which the necessity of the mathematician's reasonings and the validity of other kinds of reasonings depend, and exactly what the nature of that depen dence is. I have already pointed out that the characters that make a system of symbols good for logical [??mathematical] purposes are quite contrary to

7

those which would make it good for logical purposes. The truth is that the mathemati cian and the logician meet in one depart ment on a common highway. They meet; but one is facing one way while the other is facing just the other way. Each of them, it is true, finds it interesting to turn around occa sionally and take a glance in the opposite di rection.

The mathematician, however, has little or nothing to learn of the logician. Mathematics differs from all the special sciences whether of physics or of psychics in never encountering logical difficulties, which it does not lie entirely within his own competence to resolve.

8

The logician on the other hand has everything to learn from the mathematician. Mathematics is, with the exception of Phenomenology and Ethics, the only science from which he can draw any real guidance. There is therefore every reason in the world why we should not delay examining the fundamental nature of mathematics.

The simplest possible kind of mathematics would be the mathematics of a system of only two values. Do we in experience meet with any case in which such mathematics could have any application? I reply that we do. There are just two values that any assertion can have. It is either true when it has all the value it can have, or it is false, and

9

9

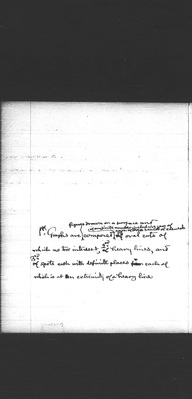

has no value at all. It follows that our system of Existential Graphs is precisely an application of the mathematics of two values. It will give you an idea of what Pure Mathematics is to imagine that the Existential Graphs to be described without any allusion whatever to their interpretation, but to be defined as symbols subject to the fundamental rules of transformation. Namely, 1st, A graph is composed of spots with definite hooks from each of which one heavy line extends 2nd, Any graph within an even number of cuts can be erased and any within an odd number of existing cuts can be inserted 3rd. Any graph can be iterated and deiterated provided the iterated or deiterated replica is not outside of any cut that the other is inside of. 4th. The cuts one inside the other with nothing between except heavy lines passing from within

10

1st. Graphs are figures drawn on a surface and composed of any finite number including zero of each of these 3 kinds of elements: 1st oval cuts of which no two intersect, 2nd heavy lines, and 3rd spots each with definite places each of which is at an extremity of a heavy line