Pages

66

122

as the smaller one. Thus, that question seems to be satisfactorily answered.

A point which often puzzles those who are entirely ignorant of the doctrine of chances is that they think that if a coin has turned up heads say ten times in succession, —which will happen about once in a thousand times,— since it must turn up heads and tails in equal proportions, the long run of heads must be followed by throws among which there is an extra proportion of tails, to balance the extra heads. This of course is a great mistake. The extra heads though they were a million would not affect the relative frequency of heads

67

124

in the long run, in the slightest degree. Everybody who has studied the doctrine of chances knows this, though perhaps not everyone understands it quite as clearly as he fancies he does, for not a few are puzzled by what is precisely the same thing, namely, the fact that it is not logically impossible that an event whose probability is zero should nevertheless occur on millions of occasions.

For example, three men, A, B, and C, agree to play a perfectly even game on the following conditions. Only two can play at a time, playing against each other; while the third stands by to take the place of the first one who goes out. At any one play one player

68

126

wins a dollar from the other and the chances are perfectly even. The dollar is not actually paid over until one of the players retires temporarily from the table, and no player does retire until he has netted a gain during the sitting. Now the doctrine of chances shows that at a perfectly even game the probability that a player whose cash and credit amount to c dollars, will net a gain of n dollars before he is ruined will be c/c+n. At this game the credit of the players is unlimited, and thus the probability will be infinity divided by infinity plus one, which fraction is strictly equal to 1. That is the probability that a player will net a gain is 1, or certainty.

69

128

Thus the three go on playing, each one as soon as he has made his absolutely certain net gain of a dollar, yielding his seat to the third; and so they keep on for all eternity, every man winning his dollar at every sitting, which dollar is paid in solid cash though the credit is unlimited while the sitting lasts.

I have known persons to find little conundrums similar to this quite puzzling.

Hume applies the doctrine of chances to disprove miracles. Now a miracle would not be a miracle if it were not entirely out of the ordinary course of nature, or what would be the course of

70

130

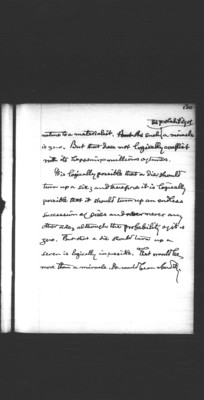

nature to a materialist. As such the probability of a miracle is zero. But that does not logically conflict with its happening millions of times.

It is logically possible that a die should turn up a six; and therefore it is logically possible that it should turn up an endless succession of sixes and never any other side, although the probability of it is zero. But that a die should turn up a seven is logically impossible. That would be more than a miracle. It would be an absurdity.