Pages

11

20

of a state of things describable in a different general statement,— and this latter general statement constitutes the conclusion. To show that this really is a correct description of Deduction, it will suffice to consider the general structure of Euclid's demonstrations,— Euclid's being more formally correct in statement than modern mathematicians think is needful. He invariably begins with a general statement of what he intends to prove. This is called the proposition; in Greek πρότασις, that is the pretension, or preliminary statement. In Aristotle it means a premiss. He then restates the condition of his proposition in such a form as to assign a selective or proper name to

12

22

every geometrical point, that is every individual of the set concerning which the predication is made. This at the same time and ipso facto describes any diagram of any state of things to which the proposition is applicable. This part ends by stating in terms of those selectives exactly what his assertion makes him responsible for. This part is called the ἔκθεσις, or exposition. Next comes his κατασκευή, or contrivance; which is an ingenious experiment that he performs upon the diagram, by adding lines to it drawn according to an exact precept, or his supposing one part to be moved and superposed in a particular way upon another part. He now shows that it is implied in what is already known that this experiment must give a certain

13

24

result in every case. This operation is his demonstration ἀπόδειξις, or from-showing. This proof ends by repeating the very statement with which the ἔκθεσις closed, to which he affixes the words, “which is what had to be shown,” ὅπερ ἔδει δεῖξαι. It is, you perceive, simply a showing that the thing is so by actual experience in the imagination. As has often been remarked, by Locke, for example, by Kant, by Stuart Mill, and as is admitted by all logicians the conclusion simply redescribes the state of things which alone is represented in the premisses.

In that sense, it does not give us any

14

26

Induction concludes more than would conceivably be true in every case in which what is observed would be true. It cannot, therefore, absolutely guarantee the truth of its conclusion. What can it do? Shall it show that the conclusion would be true in a large proportion of the embodiments of its general condition in the course of experience? This would be nothing but a necessary deduction of a statistical kind. It has to conclude that a hypothesis is true because certain predictions based upon it have been verified. Under what modification is it warranted in asserting that? Without exhausting the

15

28

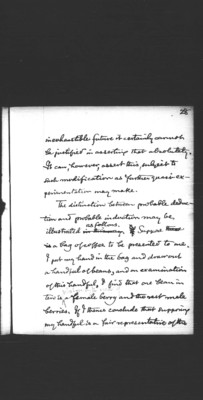

inexhaustible future it certainly cannot be justified in asserting that absolutely. It can, however, assert this, subject to such modification as further quasi-experimentation may make.

The distinction between probable deduction and probable induction may be illustrated as follows. Suppose a bag of coffee to be presented to me. I put my hand in the bag and draw out a handful of beans, and on examination of this handful, I find that one bean in ten is a female berry and the rest male berries. If I thence conclude that supposing my handful is a fair representative of the