Pages

110

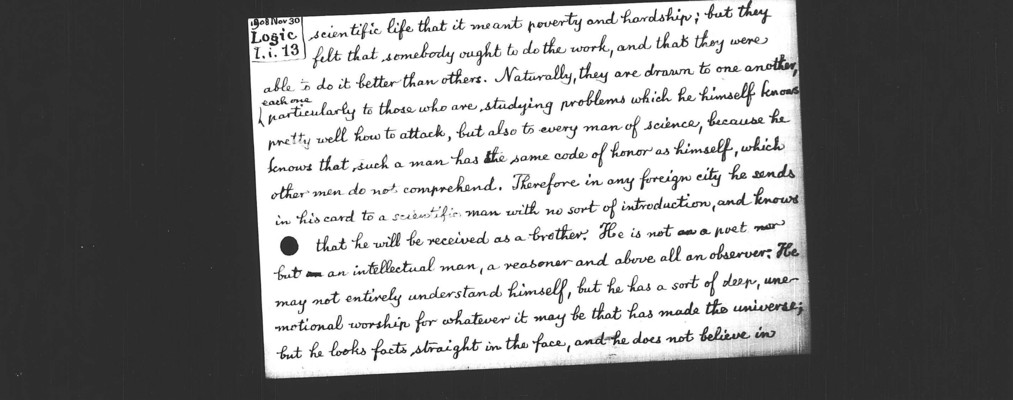

1908 Nov 30 Logic I.i. 13

scientific life that it meant poverty and hardship; but they felt that somebody ought to do the work, and that they were able to do it better than others. Naturally, they are drawn to one another, each one particulary to those who are studying problems which he himself knows pretty well how to attack, but also to every man of science, because he knows that such a man has the same code of honor as himself, which other men do not comprehend. Therefore in any foreign city he sends in his card to a scientific man with no sort of introduction, and knows that he will be received as a brother. He is not a poet but an intellectual man, a reasoner and above all an observer. He may not entirely understand himself, but he has a sort of deep, unemotional worship for whatever it may be that has made the universe; but he looks facts straight in the face, and he does not believe in

111

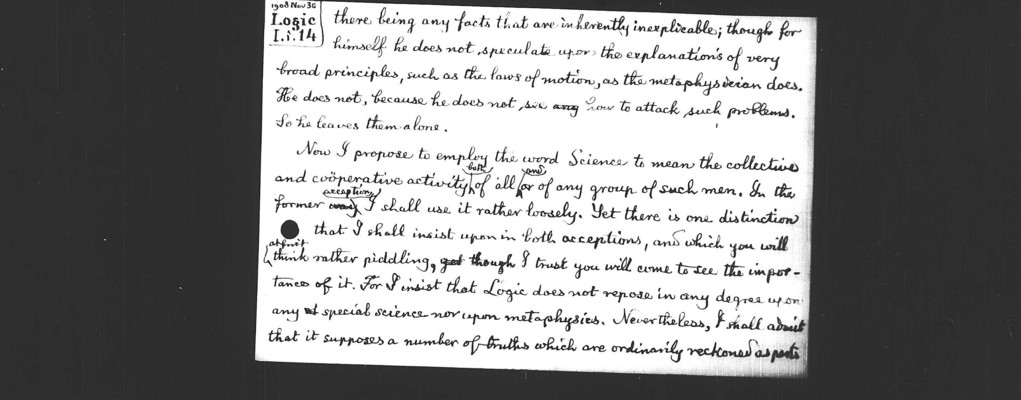

1908 Nov 30 Logic I.i. 14

there being any facts that are inherently inexplicable; though for himself he does not speculate upon the explanations of very broad principles, such as the laws of motion, as the metaphysician does. He does not, because he does not see how to attack such problems. So he leaves them alone.

Now I propose to employ the word Science to mean the collective and coöperative activity both of all and of any group of such men. In the former acception I shall use it rather loosely. Yet there is one distinction that I shall insist upon in both acceptions, and which you will [??] think rather piddling, I trust you will come to see the importance of it. For I insist that Logic does not repose in any degree upon any special science nor upon metaphysics. Nevertheless, I shall admit that it supposes a number of truths which are ordinarily reckoned as parts

112

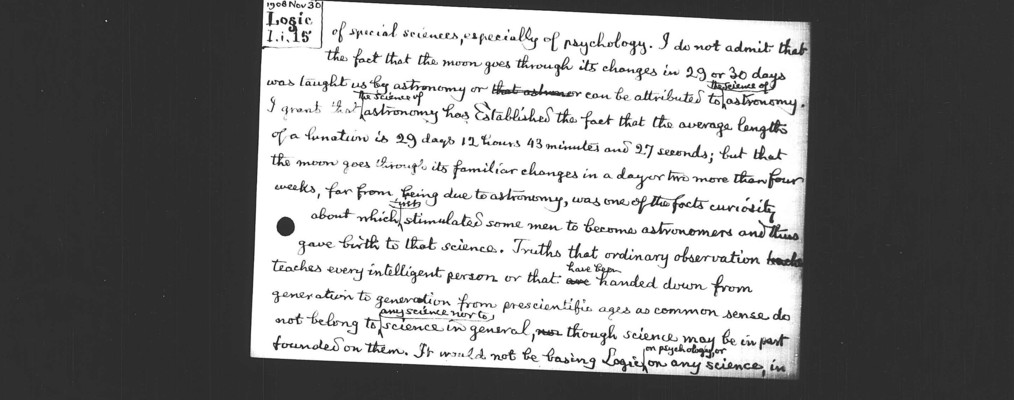

1908 Nov 30 Logic I.i. 15

of special sciences, especially of psychology. I do not admit that the fact that the moon goes through its changes in 29 or 30 days was taught us by astronomy or can be attributed to the science of astronomy. I grant that the science of astronomy has established the fact that the average length of a lunation is 29 days 12 hours 43 minutes and 27 seconds; but that the moon goes through its familiar changes in a day or two more than four weeks, far from being due to astronomy, was one of the facts curiosity about which first stimulated some men to become astronomers and thus gave birth to that science. Truths that ordinary observation teaches every intelligent person or that have been handed down from generation to generation from prescientific ages as common sense do not belong to any science nor to science in general, though science may be in part founded on them. It would not be basing Logic on psychology, or on any science, in

113

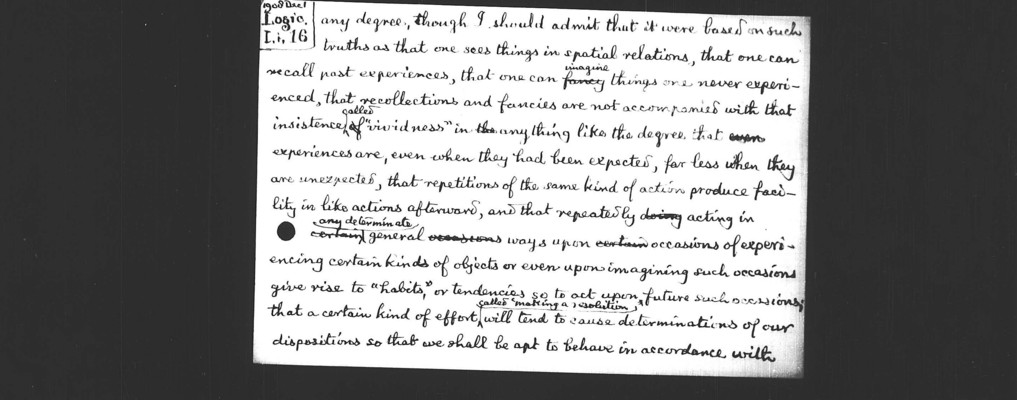

1908 Dec 1 Logic I.i. 16

any degree, though I should admit that it were based on such truths as that one sees things in spatial relations, that one can recall past experiences, that one can imagine things one never experienced, that recollections and fancies are not accompanied with that insistence called "vividness" in anything like the degree that experiences are, even when they had been expected, far less when they are unexpected, that repetitions of the same kind of action produce facility in like actions afterward, and that repeatedly acting in any determinate general ways upon occasions of experiencing certain kinds of objects or even upon imagining such occasions give rise to "habits", or tendencies so to act upon future such occasions; that a certain kind of effort called "making a resolution" will tend to cause determinations of our dispositions so that we shall be apt to behave in accordance with

114

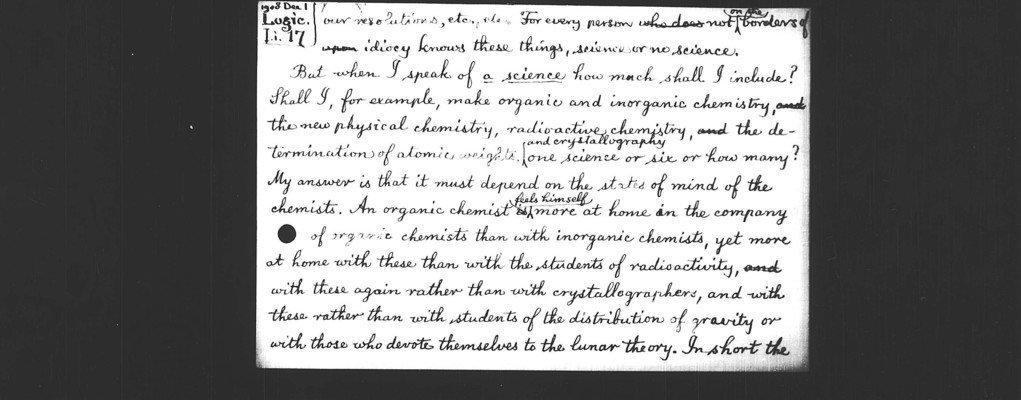

1908 Dec 1 Logic I.i. 17

our resolutions, etc., etc. For every person not on the borders of idiocy knows these things, science or no science.

But when I speak of a science how much shall I include? Shall I, for example, make organic and inorganic chemistry, the new physical chemistry, radioactive chemistry, the determination of atomic weights and crystallography one science or six or how many? My answer is that it must depend on the states of mind of the chemists. An organic chemist feels himself more at home in the company of organic chemists than with inorganic chemists, yet more at home with these than with the students of radioactivity, with these again rather than with crystallographers, and with these rather than with students of the distribution of gravity or with those who devote themselves to the lunar theory. In short the