Pages That Need Review

MS 447-454 (1903) - Lowell Lecture I

8

convincing, yet I found it too lengthy and dry; and I felt that it would abuse your patience to ask you to follow the minute eamination of all possible ways in which the conclusion and the premises might be [emended?] in hopes of finding a loop-hole of escape from the refutation. I have, therefore, decided simply to describe the phenomena presented in reasoning and then to point out to you how the argument under examination must falsify these facts however it be interpreted. This ought to satisfy you as far as this argu ment is concerned, and when you meet with other forms of the same tangle you will see for yourselves that they falsify the facts of reasoning in the same way. I had better mention that the argument I shall criticize is often to quite another objection than that which I notice,--and a more obvious one. You may wonder why I pass over it. It is

9

simply because some forms in which the same confusion of thought occurs are not often to this same objection. I only notice the radical objection that is common to all forms.

But you will think it high time I told you what this tangle of ideas of which I have said so much consists in. First let me state the fallacious argument which embodies it. The particular argument which I have chosen to exemplify it leads to a more extreme conclusion than some of the others. It does so beacuse it is less illogical than these others. Its conclusion is that there is no distinction of good and bad reasoning. Although, thus nakedly exhibited this conclusion might find few to embrace it, yet it is substantially what I might almost say that all Germany believes in today. For example, few XIXth Century treatises on logic in the German language have a [wont?] to say about fallacies, why not? Because they hold the law of logic to be, like a law of nature, inviolable. Or to state the matter

10

more exactly, enough of them hold to this opinion to set the fashion for the others. Fasion is everything among German philosophers, for the simple reason that the professers livlihood depends on his lectures being in the favored vogue. The fallacious argument itself [runs?] thus:

Every reasoning takes place in some mind. It would not be that mind's reasoning unless it satisfied that mind's feeling of logi cality ([logisches Gefiihl?]). But as long as it does that, nothing can be gained by criticizing the reasoning any further, since there is no other possible sign by which we could know that it was good than that feeling of logicality in the reasoner's mind. For if the reasoning be criticized, that criticism must be conducted by reasoning; and that reasoning, in its turn, must either be accepted because it satified the reasoner's feeling of logicality, or else be criticized by

11

further reasoning. He cannot carry through an endless series of reasonings. Therefore some final reasoning there must be that is adopted on the assumption that a reasoning which satisfied the feeling of logicality is as good as any reaosning can be; and if this be not true all reasoning is worthless. Consequently, since every reasoning satisfies the reasoner's feeling of logicality, every reasoning is as good as any reasoning can be. That is, there is no distinction of good and bad reasoning.

That is the argument which I pronounce a miserable fallacy. If we extend to arguments just maxim of our law, every argument must be presumed to be sound until it is proved fallacious. Accordingly, I will refer to this argument as the "defendent-argument," and

12

to the writers who adhere to is as the "defendents."

In order to emphasize that confusion which I think so pestilent and to prevent your mind's from being distracted from it to another fault in the defendent argument, I put it into parallel with another argument that involves one quite analogous confusion.

Namely, we find in some of the old writers a fallacious argument to prove that there is no distinction of moral right and wrong. The argument runs as follows:

The distinction between a good act and a bad one, if ther be any such distinction, lies in the motive But the only motive a man can have is his own pleasure. No other is thinkable. For if a man desires to act in any way, it is because he takes pleasure in so acting. Otherwise, his action would not be voluntary and deliberate.

18

18

in the main, have been imbibed in childhood. Still they have gradually been shaped to his personal nature and to the ideas of his circle of society rather by a continuous process of growth than by any distinct acts of thought. Reflecting upon these ideals, he is led to intned to make his [?] conduct conform at least to a part of them, to that part in which he throughtly believes. Next, [?] usually formulates, however vaguely, certain rules of conduct. He can hardly help doing so. Besides such rules are convenient and served to minimize the effects, future inadvertence and what are named the wiles of the devil within him. Reflection upon these rules as well as upon the general ideals behind them, has a certain effect upon his disposition, so that what he naturally incline to so becomes modified. Such being his condition, he often foresees that a special occaion is going to arise; There upon, a certain gathering of his forces begn to work and this working of his being will cause him to consider how he will act and in accordance with his disposition, such as it now is, he is led to form a resolution as to how he will act upon that occasion. This resolution is of the nature of a plan: or one might almost sat, a diagram. It is a mental formula always

113

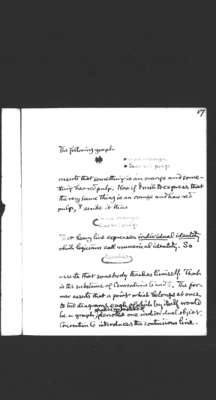

17

The following graph *is an orange *has red pulp asserts that something is an orange and something has red pulp. Now if I wish to express that the very same thing is an orange and has red pulp, I scribe it thus (Is an orange has red pulp that heavy line expresses individual identity which logicians call numerical identity. So (teaches) asserts that somebody teaches himself. That is the substance of Conventions 5 and 6. The former asserts that a point which belongs at once to two diagrams each of which by itself would be a graph, shall be understood to denote one individual object. Convention 6 introduces the continuous line.

114

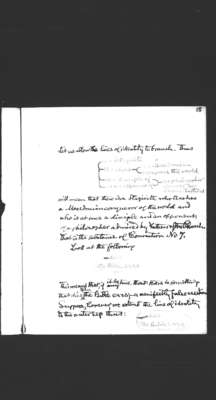

18

let us allow the lines of identity to branch. Thus

|-is a Stagirite |-teaches- is a llaced onion - conquers the world |-is a disciple of - is a philosopher admired by church fathers |-is an opponent of will mean that there id a stagirate who teaches a Macedonian conqueror of the world and who is at once a disciple and an opponent of a philosopher admired by fathers of the Church. That is the substance of Convention No 7. Look at the following -dies (the Bible errs This means that, if it be true that there is something that dies then the Bible errs;-a manifestly false assertion. Suppose - however, we extend the line of identity to the outer sep thus: (-dies the Bible errs)

115

19

Now this point on the sep denotes an existing individual. I assume that our universe of discourse is the totality of all historical men. We can hardly avoid interpreting the graph as meaning that if an individual man dies (say perhaps Enoch ot Elijak), the Bible errs. So take this. It means that if there

-is a salamander (-is a salamander -lives in fire -live in fire be a salamader something lives in fire; and the meaning will not be affected by prolonging the outer line of identity to the inner sep. If however we join the two lines of identity, thus, (is a salamander lives in fire we can hardly resist the interpretation, 'If anything is a salamander that very same thing lives in fire, that is, whatever

118

22

does, has no meaning. That is, it leaves the sheet with the same meaning after it was written that it had before. Neverthe less, I call it a graph. I call the blank sheet of assertion a graph. For it stands to graphist and interpreter for all that they agree to. On the other hand, an expression which contradicts what graphist and interpreter have agreed that they will not deny, such as 'Nothing is true', or

(is a proposition is not true

violates the first convention, and is therefore not properly an expression of this system. I do not call that a graph, but the pseudograph. I say not a pseudograph but the pseudograph because all such expressions are equivalent in this system, all being alike violations of the conventions. To make the oseudograph on the sheet of assertion would