Pages That Mention Columbia River

Coast Guard District narrative histories 1945

44

One of the most remarkable advances in inland marine navigation was that which tranferred the swirling waters of the Columbia river into 300 miles of navigable waterway. In 1805, when Lewis and Clark concluded their amazing trek to the Northwest Coast, vast portions of the Columbia River defied the explorers' attempts to transport their party and supplies on its broad expanse. Almost 140 years later, great ocean-going vessels were able to ply their way into Oregon and Washington river ports.

The wildness of the river lay in the swiftness of the water forming treacherous whirlpools and rapids over the shallow, jagged bottom. To eliminate this danger, two great projects were undertaken: The Bonneville Dam and the Celilo Canal. Although the canal was finished before World War I, river traffic to The Dalles, Oregon, and beyond, had ceased around 1916. In 1932, navigation in this section was revived for the transportation of wheat, but the service between the Upper and Lower ports was intermittent. This renewal of navigation was more or less on a trial basis to determine if sufficient commerce could be developed to support water carrier operation.

Sufficient traffic was realized and, after the construction of the Bonneville Dam which was completed in 1938, river traffic expanded into the movement of great steel barges designed to carry liquid petroleum in the hull and package or bulk cargo on deck. With this increase of traffic from Astoria, Oregon, beyond The Dalles, Oregon, the necessity of navigational aids to insure the mariner's safety became most apparent. As a result, the Seattle District centered the majority of its activities in the promotion of safe navigation along the river. Here was the proving grounds for experimental light structures and buoys to determine those most suitable for the area. Due to the rapid current, ranges marking channels had to be so perfected as to enable the mariners to ascertain his course in split-second timing.

The sheer steep cliffs of this area presented problems in erecting shore structures and the swift waters made the mooring of buoys almost impossible. Even before the consolidation of the Lighthouse Service and the Coast Guard, the problems of marking the river had been of primary importance to the Lighthouse Service and basic markings had been established along the banks. The last allotment made to the Service in 1939 was for the establishment of additional lights in the Columbia, Umpqua and Yaquina Bay. River traffic

-25-

46

actuality except for the initial voyage of such a vessel to The Dalles, Oregon, in 1939 to prove the channel was large enough for traffic of this type. A conference with marine interests was held in 1943 and a program for proposed aids between Vancouver, Washington and Bonneville was drawn up. The necessity for additional aids was intensified by the continual requests from government agencies to increase the total tonnage on the Columbia River because, due to the manpower shortage, inexperienced men were operating vessels over these treacherous waters and also because almost all railroad tank cars had been taken out of the area due to the war emergency. This placed an exceedingly large burden on the water carriers to transport the required petroleum products for the Army and Navy Air Forces on the Columbia River. The area was marked, at that time, by 6 ranges, 26 lights and 2 beacons.

The new program presented to Headquarters in 1945 requested that 51 structures be electrified and that duplex lanterns be replaced by single General Railway signal, Type "SA" lanterns in order to simplify and standardize equipment. This proposed project was approved by Headquarters and work began instantly. The contour of the shore in this area, near Multnomah Falls, created precipitous cliffs rising almost from the water's edge which prevented the use of the customary range, and, consequently, it was proposed to install experimental channel limiting group lights which had been temporarily established at Arlington beyond The Dalles, Oregon. (See Arlington Channel Limiting Group Lights under "Experimental Range Markings".) Headquarters disapproved the use of the new ranges and as a result, the area was left inadequately marked as the conventional two board ranges could not be established on the sheer banks. (A great number of the rear lights of conventional ranges installed above Celilo were fixed instead of flashing. When the lights were first installed, both front and rear lights were flashing. As this section of the river was very dangerous due to the rocks and whirlpools and side currents, the operators of the boats had very little time for observation of ranges which were astern when going up the rapids as the current and the whirlpools were continually changing the boat's course. If the light was at an eclipsed state when the operator looked back at the range, he was unable to determine whether or not he was on the course as very little time could be spent looking for the range.)

-27-

47

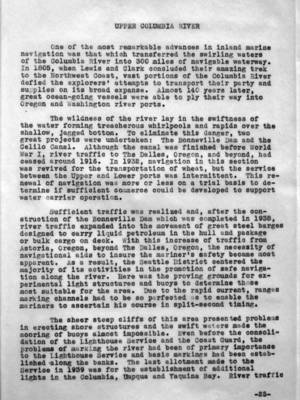

(picture)

THE PICTURE SHOWS AN INLAND NAVIGATION CO. BARGE ST(R)ANDED IN THE CELILO RAPIDS, GIVES AN IDEA OF THE DIFFICULT CHANNELS, THE SWIFT AND SHALLOW WATER, AND THE GENERAL TERRAIN WITH WHICH NAVIGATORS IN THIS VICINITY MUST COPY. THE BARGE HAD BROKEN LOOSE FROM ITS MOORINGS AND DRIFTED TO THIS PRECARIOUS POSITION. IT WAS FLOATED BY THE RELEASE OF A HEAD OF WATER FROM COULEE DAM WHICH TOOK 2 TO 3 DAYS TO REACH THE AREA. RESCUE WAS CONDUCTED BY CABLES BETWEEN MEN ON THE BARGE AND THE SHORE AS POWER BOATS WERE NOT ABLE TO ENTER THE RIVER AT THIS POINT. THE NAVIGATION CO. REALIZED CONSIDERABLE LOSS IN THIS PARTICULAR CASE ALTHOUGH INSTANCES OF THIS TYPE ARE NOT UNCOMMON IN RIVER TRAFFIC. THIS BARGE IS TYPICAL OF THOSE FOUND IN THE COLUMBIA RIVER AREA.

EXPERIMENTAL BUOYS

The area between Bonneville, Oregon, and The Dalles, Oregon, consisted of two deep water pools which were formed by the construction of the Bonneville Dam and was well lighted with numerous river bank lights. a meeting with vessel operators a few months before the war resulted in the unanimous approval of the lights as they were at that time. Requests were constantly made for installation of buoys but none were developed which could ride the swift current during freshets. Oil drum buoys were set out in the vicinity of Celilo and, at the conclusion of the war, were still the most effective buoy markings. The buoys had been painted white, with red or black band markings as the navigators had found it difficult to pick out the solid red or black buoys at night. The mariners urged the development of a surface riding buoy equipped with reflectors as reflectors could not be installed on the oil drums. The dependency of tugboat operators on these markings was evidenced in the fact that if the tender assigned to that area was unable to replace an

_28-

48

oil drum, the operator himself would pick up the drum and sinker and place it on station en route. Early in 1941, this was common practice as that section between The Dalles, Oregon and Umatilla, Oregon, was seriously handicapped by the lack of sufficient boat equipment. At the beginning of the war, an especially built 65' buoy boat was assigned to that area.

Experiments were made to determine the effectiveness of surface riding buoys, the first being with a Wallace and Tiernan and a 13th District boat type buoy, designed for the Columbia River. The buoys were placed on station in the Upper Columbia where the current was 8 miles per hour. The Wallace and Tiernan buoy was lost a month after its installation and a careful search of the river banks and dragging the river bottom failed to produce it or its mooring. Reports indicate that, until the time it disappeared, it had performed in an extremely satisfactory manner. The 13th District buoy was still in place at the conclusion of the war.

On the following page are photographs of the Headquarters pre-fabricated fast water buoy during assemblage and on station. The illustration of the boat type buoy is the District buoy which was placed on station and which at the conclusion was still in position. The Headquarters buoy did not prove equally successful.

(image) HOUSER FAST WATER BUOY

At Vancouver, Washington, Experiments were conducted in the use of Scotchlite, which is a plastic reflector material, on daymarks in the summer of 1943. Its success paved the way for similar installations on beacons in the Upper Columbia around The Dalles, Oregon. However, due to the heavy sands which stuck to the Scotchlite, it was abandoned in favor of the reflector buttons which protruded far enough from

-29-

53

Tests of the channel limiting group equipment were observed by the District Engineering and Marine Inspection Officers and it was their recommendation that it was worthwhile to establish and to put into use such an experimental range on the Columbia River. This was done at Arlington, Oregon, with Headquarters' approval, in the Spring of 1945. An investigation of the success of this type of range indicated that the majority of the operators preferred the old type regular center line lighted range of two boards. This preference, in the opinion of the District Coast Guard Office, was made primarily because of the lack of understanding and the use of the limiting channel range and, consequently, detailed printed instructions were issued to all operators in the Celilo-Pasco District where the Arlington range was located. As a result, more favorable comments were received in regard to the use of the limiting channel lights, but, notwithstanding, Headquarters would not authorize their establishment on other ranges where the two-board range was impracticable because of the terrain. This policy, which Headquarters adopted, left areas in the Columbia River unsafe for navigation as the lights and markings which could be established there provided only inadequate coverage.

INCREASE OF AIDS AND CHANNEL IMPROVEMENTS

Recommendations for the increase of aids to insure safety of mariners in the Upper Columbia were presented to the District Coast Guard Officer and Headquarters by the Board of Survey. Headquarters felt that complete justification for the project as a whole, as being vital to the war effort, had not been furnished, and requested that a complete list of all shipping interests concerned, the extent of their operations, and a list of all government agencies involved there in the war interest, be furnished. Letters from navigation companies indicating the large burdens placed on water carriers to transport the required petroleum products to Army and Navy installations on the Columbia were forwarded to Headquarters together with freight tonnages and traffic statistics. The proposed improvements were then approved and an appropriation of $50,000 was granted. (June, 1940). Additional appropriations were granted later.

The Snake River, which enters the Columbia just south of Pasco, Washington, was not navigable except during high water from the middle of March to the middle of July. At the time of the survey, the U. S. Army Engineers were contemplating the improvement of the Snake River by providing a

-33-