Pages

51

96

a Uniformity and that there is a Law? It is simply that phenomena being conceived as having already occurred, any agreement in the ideas they excite in the mind, is a Uniformity while a Law is something which has some sort of being in advance of the occurrences and the occurrences all conform to it. It is plain that this Uniformity of Nature was for Stuart Mill a great Law, although it never occurred to him that in holding to it he was really cutting loose from his traditional Nominalism.

I have long ago fully expressed myself about Mill's Logic. I am not

52

98

a Nominalist. I am a scholastic Realist of an extreme type. I not only believe that Laws really are, but it seems to me evident that Laws really live, and that they are the only things that do live, the only things whose being is complete. Accordingly, I have no disposition to deny Mill's Uniformity of Nature simply because it is a law. Nevertheless, I do deny it. It seems to me plain enough that Nature is not absolutely uniform in any positive sense. Variety, on the contrary, is the leading characteristic of Nature; and the uniformity of it is only just barely sufficient to make things go

53

100

pretty regularly.

But this is metaphysics; and it is neither the psychological question nor the metaphysical question concerning induction,— interesting as each of them certainly is,— that concerns us now. It is the logical question how can we be justified in drawing an induction? “Justified,” I say. That is, how far does it conduce to our purpose. What is our purpose? It is to form such habits of thinking that events will not surprise us. So the question is how does the making of an induction conduce to the formation of such habits of thinking that the events

54

102

when they come shall merely realize our anticipations, and prevent anticipations that are not realized?

My own answer to this question has already been made clear. Namely, the answer is that induction is such a way of inference that if one persists in it one must necessarily be led to the truth, at last. It is true that this condition is most imperfectly[?] fulfilled in the Pooh-pooh argument. For here the unexpected, when it comes, comes with a bang. But then, on the other hand, until the fatal day arrives, this argument causes us to anticipate just what does happen and prevents us from anticipating a thousand things that do not happen. I engage a stateroom; I purchase a letter of

55

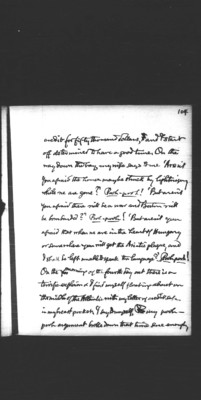

104

credit for fifty thousand dollars, and I start off determined to have a good time. On the way down the bay, my wife says to me ‘Aren't you afraid the house may be struck by lightning while we are gone?’ Pooh-pooh! ‘But aren't you afraid there will be a war and Boston will be bombarded?’ Pooh-pooh! ‘But aren't you afraid that when we are in the heart of Hungary or somewhere you will get the Asiatic plague, and I shall be left unable to speak the language?’ Pooh-pooh! On the morning of the fourth day out there is a terrific explosion and I find myself floating about in the middle of the Atlantic with my letter of credit safe in my breast pocket. I say to myself, my pooh pooh argument broke down that time sure enough,