Pages

61

116

In order to avoid too advanced mathematics and too great intricacies, I am compelled to take for my example a problem where the Laplacian method leads to much better results than it does in those problems to which Laplace applies it. I must ask you to make allowance for this.

The problem is this. Suppose there comes to the port of New York a large cargo of many thousand boxes of toys, each containing ten toys, all different in any one box, but possibly recurring in different boxes. Now the custom-house inspector proceeds in this way. He

62

118

selects a box by a method calculated in the long run to bring out one box as often as another. He shakes up the box well and then putting his hand into it grabs the first toy his hand touches, which he examines as to its being dutiable or not, after which he then goes on in the same way with another box. Now suppose that proceeding in this way the Inspector has found the first five toys to be dutiable, the question is what is the probability that the sixth toy is so.

I will first give my answer to this problem, secondly I will give Laplace's presumable treatment of it, and thirdly I will go on to show you that the latter is absurd. My answer is that we are tolerably safe in inferring that the great majority of

63

122

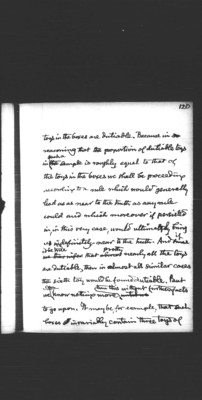

toys in the boxes are dutiable. Because in reasoning that the proportion of dutiable toys in such a sample is roughly equal to that of the toys in the boxes we shall be proceeding according to a rule which would generally lead us as near to the truth as any rule could and which moreover if persisted in, in this very case, would ultimately bring us indefinitely near to the truth. And if it be true that pretty nearly all the toys are dutiable, then in almost all similar cases the sixth toy would be found dutiable. But we can know nothing more than this without further facts to go upon. It may be, for example, that such boxes invariably contain three toys of

64

122

a kind not dutiable and that the fact that all the first five drawn were dutiable is simply an extraordinary coincidence. How this may be we do not know, as long as we do not know how the contents such boxes are usually made up,— even in the long run, to say nothing of this particular cargo.

The Laplacians reason, however, as follows. They say that there might be in each box either 10, 9, 8, 7, 6, 5, 4, 3, 2, 1 or no dutiable toys. These they say are simple possible events. They lay great stress on events being simple, although they never tell us what they mean by it and appear to call any events simple which they

65

124

are not led to view as compounded. They further say that these happening are equally possible, “également possible” is the phrase which Laplace introduces at the beginning of his book, without telling us what scintilla of meaning can be attached to it. Certainly anybody talking French would say they were également possible,— that is, one as truly possible as another. But également, in that sense, is not an expression of quantity. But Laplace always proceeds as if events which are également possible and which are also simple events, were equally probable, which if equally probable means equally