Pages That Need Review

Manuscript Cookbook 208

ksul-uasc-mscc208_006

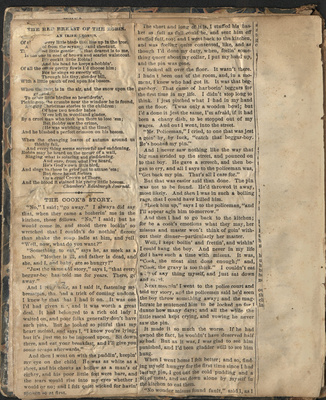

[[first column]] THE RED BREAST OF THE ROBIN. AN IRISH LEGEND

Of a[ll the m]erry little birds that live up in the tree, A[nd car]ol from the scyam[or]e and chestnut, Th[e pretti]est little gentle[man] that dearest is to me, Is the one in coat of brown and scarlet waistcoat. It's Cockit little Robin! And his head he keeps a-bobbin'. Of all the other pretty fowls I'd choose him; For he sings so sweetly still, Through his tiny, slender bill, With a little patch of red unpon his bosom.

When the frost is in the air, and the snow upon the ground, To other little birdies so beweilderin', Picking-up the crumbs near the window he is found, Singing Christmas stories to the children: Of how two tender babes Were left in woodland glades, By a cruel man who took 'em there to lose 'em; But Bobby saw the crime, (He was watching all the time!) And he blushed a perfect crimson on his bosom.

When the changing leaves of autumn around us thickly fall, And every thing seems sorrowful and saddening, Robin may be heard on the corner of a wall, Singing what is solacing and gladdening. And sure, from what I've heard, He's God's own little bird, And sings to those in grief just to amuse 'em; But once he sat forlorn On a cruel Crown of Thorn, And the blood it stained his pretty little bosom. Chambers' Edinburgh Journal.

--------------

THE COOK'S STORY.

"No," I said; "go away." I always did say that, when they came a botherin' me in the kitchen, those fellow. "No," I said; but he would come in, and stood there lookin' so wretched that I couldn't do nothin' fiercer than shake the soup ladle at him, and yell "Well, now, what do you want?"

"Something to eat," says he, as meek as a lamb. "Mother is ill, and father is dead, and she, and I, and baby, are so hungry!"

"Just the same old story," says I, "that every beggar-boy has told me for years. There, go away."

And I remember, as I said it, fastening my breastpin, that had a trick of coming undone. I knew by that that I had it on. It was one I'd had given me, and it was worth a great deal. It had belonged to a rich old lady I waited on, and poor folks generally don't have such pins. But he looked so pitiful that my heart melted, and says I, "I know you're lying, but it's just me to be imposed upon. Sit down there, and eat your breakfast, and I'll give you some scraps aferwards."

And then I went on with the puddin', keepin' my eye on the child. He was as white as a sheet, and his cheeks as hollow as a man's of eighty, and his poor little feet were bare, and the tears would rise into my eyes whether I would or no; and I felt quite wicked for havin' spoken so at first.

[[second column]] The short and long of it is, I stuffed his basket as full as full could be, and sent him off stuffed full, too; and I went back to the kitchen, and was feeling quite contented, like, and as though I'd done my duty, when, feelin' something queer about my collar, I put my hand up, and the pin was gone.

I looked all over the floor. It wasn't there. I hadn't been out of the room, and, in a moment, I knew who had got it. It was that beggar-boy. That came of harborin' beggars for the first time in my life. i didn't stop long to think. I jest pitched what I had in my hand on the floor. 'Twas only a wooden bowl; but I'd a done it jest the same, I'm afraid, if it had been a chany dish, to be stopped out of my wages. And out I went, into the street.

"Mr. Policeman," I cried, to one that was jest goin' by, by luck, "catch that beggar-boy. He's hooked my pin."

And I never saw nothing like that way that big ma nstrided up the street, and pounced on to that boy. He gave a screech, and then began to cry, and all I says to the policeman was, "Get back my pin. That's all I care for."

But that was easier said than done. The pin was not to be found. He'd throwed it away, most likely. And then I was in such a boiling rage, that I could have killed him.

"Lock him up," says I to the policeman, "and I'll appear agin him to-morrow."

And then I had to go back to the kitchen; for be a cook's emotions what they may, her missus and master won't think of goin' without their dinner--particularly her master.

Well, I kept boilin' and frettin', and wishin' I could hang the boy. And never in my life did I have such a time with missus. It was, "Cook, the meat aint done enough;" and, "Cook, the gravy is too thick." I couldn't eat a bit of any thing myself, and just sat down and cried.

Next mornin' I went to the police court and told my story, and the policemen said he'd seen the boy throw something away; and the magistrate he sentenced him to be locked up for I dunno how many days; and all the while the little rascal kept crying, and vowing he never saw the pin.

It made it so much the worse. if he had owned the fact, he wouldn't have deserved half so bad. But as it was, I was glad to see him punished, and I'd be gladder still to see him hung.

When I went home I felt better; and so, finding myself hungry for the first time since I had lost my pin, I got out the cold pudding and a bit of meat, and sat down alone by myself in the kitchen to eat them.

"No wonder missus found fault," said I, as I

ksul-uasc-mscc208_007

[[First column]]

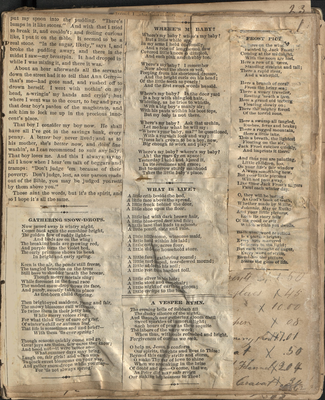

put my spoon into the pudding. "There's lumps in it like stones." And with that I tried to break it, and couldn't; and feeling curious like, I put it on the table. It seemed to be a real stone. "In the sugar, likely," says I, and broke the pudding away; and there in the midst I saw--my breastpin. It had dropped in while I was mixing it, and there it was.

About an hour afterwards all the servants down the street had it to tell that Ann Gerry- that's me--had gone mad, and rushed off to drown herself. i went with nothin' on my head, a-wringin' my hands and cryin'; but where I went was to the court, to beg and pray that dear boy's pardon of the magistrate, and ask him to lock me up in the precious innocent's place.

That boy I consider my boy now. He shall have all I've got in the savings bank, every penny. A better boy never lived; and as to his mother, she's better now, and doin' fine washin', as I can recommend to suit any lady. That boy loves me. And this i always say to all I know when I hear 'em talk of beggars and tramps: "Don't judge, lest, as our parson reads out of the Bible, you may be judged yourself by them above you."

Those aint the words, but it's the spirit, and so I hope it's all the same.

---------

GATHERING SNOW-DROPS.

Now passed away is wintry night, Comes back again the sunshine bright, The golden flow of ruddy light- And birds are on the wing; The breaking buds are growing red, And purple turns the violet bed, The early primrose shows its head in bright and early spring.

Keen is the air, the ponds still freeze, The tangled branches on the trees Still bare to shudder 'neath the breeze, Through merry mortals sing; While foremost in the floral race The modest snow-drop shows its face, And purely, sweetly take it's place As first-born child of spring.

Then bright-eyed maidens, young and fair, The snowy blossoms cull with care, To twine them in their jetty hair While merry voices ring; For what think they of care or grief, Of winter's chill or autumn leaf, That life is sometimes sad and brief?- With them 'tis ever spring!

Though seasons quickly come and go, Great joys are theirs, few cares they know; And heed not--it were better so- What summer days may bring. Laugh on, fair girls! and often stay, To pluck sweet blossoms on your way, And gatter snow-drops while you may- For 'tis not always spring!

[[Second Column]]

WHERE'S M' BABY?

Where's my baby? where's my baby? But a little while ago, In my arms I held one fondly, And a robe of lengthened flow Covered little knees so dimpled, And each pink and chubby toe.

Where's my baby? I remember Now about the shoes so red, Peeping from his shrotened dresses, And the bright curls on his head; Of the little teeth so pearly! And the first sweet words he said.

Where's my baby? In the door yard Is a boy with shingled hair, Whittleing, as he tries to whistle, With a big boy's manly air; With his pants within his boot tops, But my baby is not there.

Where's my baby? Ask that urchin, Let me hear what he will say: "Where's your baby, nma?" he questioned, With a rognish look and way; "Guess he's grown to be a boy, now, Big enough to work and play."

Where's my baby? where's my baby? Ah! the years fly on apace! Yesterday I held and kissed it, In its loveliness and grace; But to-morrow sturdy manhood Takes the little baby's place.

--------

WHAT IS LIFE?

A little crib beside the bed, A little face above the spread, A little frock behind the door, A little shoe upon the floor.

A little lad with dark brown hair, A little blue-eyed face and fair; A little lane that leads to school, A little pencil, slate and rule.

A little blithesome, winsome maid, A little hand within his laid; A little cottage, acres four, A little old-time household store.

A little family gathering round; A little turf-heaped, tear-dewed mound; A little added to his soil; A little rest from hardest toil.

A little silver in his hair; A little stool and easy-chair; A little night of earth-lit gloom; A little cortege to the tomb.

---------

A VESPER HYMN.

The evening bells of Sabbath fill The dusky silence of the night, And through our gathering gloom distil Sweet sparkles of immortal light; Such hours of peace as theserequite The labors of the weary week; When thus, with souls refreshed and bright, Forgiveness of our sins we seek.

O help us, Jesus, to conform Our spirits, thoughts and lives to Thine! Beyond this earthly strife and storm, O make Thy star of love to shine When we are sinking in the brine Of doubt and care--O come, that we, As Peter did, may safe resign Our sinking helplessness to Thee!

[[Third Column]]

FROST PICT[URES] [Pictu]res on the win[dow,] [Pai]nted by Jack Frost, Coming at the midnight, With the noon are lost. Here a row of [fir-]trees, Standing straight and tall; There a rapid river, And a waterfall.

Here a branch of coral From the briny sea; There a weary traveller, Resting 'neath a tree Here a grand old iceberg Floating slowly on; There the mighty forest Of the torrid zone.

Here a swamp all tangled, Rushes, ferns and brake; There a rugged mountain, Here a little lake. Thus a breath, the lightest Floating on the air, Jack Frost catches quickly, And imprints it there.

And thus you are painting, Little children, too, On your life's fair window Always something new. But your little pictures Will not pass away, Like those Jack Frost's [fin]gers Paint each winter day.

O, they will be lasting As God's book of truth, Whether made by Willie, Johnnie, May or Ruth; And your little pictures, Each its story tells Of the good or evil Which within you dwells.

Each kind word or action [Is a] picture bright; Every [duty] mastered Is [lovel]y in the light; But each thought of anger, Every word of strife, Blemishes the picture, Stains the glass of life.

-------

[[handwritten]] -ints x 1.50 -gcloves x 45 x 10.00 -pen x .08 -ing [?]bou x 17.01 -at x .50 Flannel x 2.04 Cravat x 34 --562 [[/handwritten]]

ksul-uasc-mscc208_009

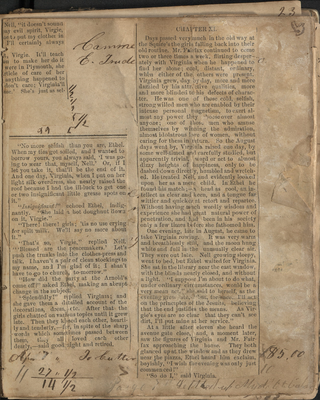

[[upper-left corner]] [[newspaper cutting]] Nell, "it doesn't sound say evil spirit, Virgie, net, put my clothes in I'll certainly always

t, Virgie. It'll teach on to make her do it were in Plymouth, she rticle of care of her anything happened to don't cae; Virginia'll me.' She's just as sel[[/newspaper]] [[handwritten]] Camme E. Trude 1/2 [?] 5 1/2

| 99 | 5 |

|---|

[[left column]] "No more selfish taht you are, Ethel. When my ties got soiled, and I wanted to borrow yours, you always said, 'I was going to wear that, myself, Nell.' Or, if I let you take it, that'll be the end of it. And one day, Virginia, when I put on her light silk overdress, she nearly raised the roof because I had the ill-luck to get one or two insignificant little grease spots on it."

"Insignificant!" replied Nell. "'Blessed are the peacemakers.' Let's push the trunks into the clothes-press and talk. I haven't a pair of clean stockings to my name, and I'm glad of it; I shan't have to go to church, to-morrow."

"How did the party at the Arnold's come off?" asked Ethel, making an abrupt change in the subject.

"Splendidly!" replied Virginia; and she gave them a detailed account of the decorations, dress, etc. After that the girls chatted on various topics until it grew late. Then they kissed each other, heartily and tenderly,--for, in spite of the sharp words which sometimes passed between them, they all loved each other dearly,--said good night and retired.

[[handwritten]] Ap[ril?] 7 " To Cutting 27 " 1/2 ---------14 1/2 [[/handwritten]] [[/left column]]

[[right column]] CHAPTER XI.

Days psssed very much in the old way at the Squire's the girls falling back into their old routine. Mr. Fairfax continued to come two or three times a week, flirting desperately with Virginia when he happened to find her alone; cool, distant, ordinary, when either of the others were present. Virginia grew, day by day, more and more dazzled by his attractive qualities, more and more blinded to his defects of character. He was one of those cold, selfish, strong willed men who are enabled by their intense personal magnetism, to exert almost any power they choose over almost anyone; one of those men who amuse themselves by winning the admiration, almost idolatrous love of women, without careing for them in return. So the August days went by, Virginia raised one day, by some well-timed and carefully studied, but apparently trivial, word or act to almost dizzy heights of happiness, only to be dashed down directly, humbed and wretched. He treated Nell, and evidently looked upon her as a mere child. in Ethel he found his match;--a head as cool, an intellect as clear and keen, and a toungue far wittier and quicker at retort and repartee. Without having much wordly wisdom and experience she had a great natural power of penetration, and had been in his society only a few times before she fathomed him.

One evening, late in August, he came to take Virginia rowing. it was very warm and breathlessly still, and the moon hung white and full in the usually clear air. They were out late. Nell growing sleepy, went to bed, but Ethel waited for Virginia. She sat in the library near the east window, with the blinds nearly closed, and without a light. "I suppose I'm about to do what, under ordinary circumstances, would be a very mean act," she said to herself, as the evening grew [l?]ate, 'but, for once, I'll act on the principles of the Jesuits, believing that the end justifies the means. As Virgie's eyes are so clear that they can't see dirt, I'll put mine at her service."

At a little after eleven she heard the avenue gate close, and, a moment later, saw the figures of Virginia and Mr. Fairfax approaching the house. They both glanced up at the window and as they drew near the piazza, Ethel heard him exclaim, boyishly, "I wish the evening was only just commenced!"

"So do I," said Virginia.

ksul-uasc-mscc208_012

Original Story. [Written expressly for the Messenger]

Virginia Thorns; or the Story of a Spanish Ring.

by Anna C. Field.

Chapter XII

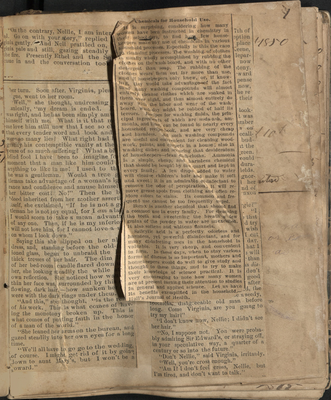

The next day passed, as days do, with its petty events occurring precisely as they always do, whether our hearts are merry or broken. Virginia wondered that the house should pass the same as they had done when she was comparatively happy. She was dimly conscious that she had prepared herself for something different. Neil, never particularly observant, did not appear to notice any change in Virginia's manner. Ethel, knowing all, said nothing and the dear old Squire, thinking she was simply indisposed, told her he was sorry but that the time for their mountain trip was not dar off, and that the change would do her good. The next day but one Mr. Fairfax left town with the Arnold's to be gone a month. Just before his return the Squire and Virginia left to spend the first half of October at the White Mountains. Ethel has told her, and Virginia has almost persuaded herself to believe that once away from Warwick, and among scenes entirely new and full of romantic beauty, her sorrow would fade away from her mind, and she would be enabled to regard Mr. Fairfax with the same calm indifference with which she has formerly regarded him.

ksul-uasc-mscc208_013

Cutout of page located on top of anoter

Top cutout:

It is surprising, considering how many women have been instructed in chemistry in their school-days, to find how few housekeepers make any use of chemicals in various household processes. Especially is this the case in cleansing processes. The washing of clothes is usually wholly accomplished by rubbing the clothes on the wash-board, and with no other detergent than soap. The rubbing of the clothes wear them out far more than use, and if housekeepers only knew, or, if knowing, they would take advantage of the fact that many washing compounds will almost entirely cleanse clothes which are soaked in them over night, and thus almost entirely do away with the labor and wear of the wash-board, washday might be robbed of half its terrors. Recipes for washing fluids, the principal ingredients of which are soda-ash, ammonia and lime, can be found in nearly every household recipe-book, and are very cheap and harmless. All such washing compounds are useful and convenient for cleaning wood -work, paints, and carpets in a house; also in washing dishes and scouring that desideratum of housekeepers -- clean dish-cloths. Ammonia is a simple, cheap, and harmless chemical that should be bought by the quart and kept in every family. A few drops added to water will cleanse children's hair and make it soft and sweet; it is an admirable disinfectant to remove the order or perspiration; it will remove grease-spots from clothing and often restore colors to stains. Its command and frequent use cannot be too frequently urged. Borax is another chemical that should find a common use in every family. For cleansing the teeth and sweetening the breath a few grains of the powder in water are unexcelled. It also softens and whitens flannels. Salicylic acid is a perfectly odorless and harmless, yet powerful disinfectant, and for many disinfecting uses in the household is valuable. It is very cheap, and convenient in form. In these days, when to stay various forms of disease is so important, mothers and housekeepers would do well to give study and though to these things, and to try to make their knowledge of science practical. It is very encouraging to note how many women are at present turning their attention to studies in general and applied science. Let us have its benefits exemplified in the household. Hall's Journal of Health.

Under cut left side:

"On the contrary, Nellie, I am inter [?] ed. Go on with your store." replied [?] ginia pale and still, gazing steadily [?] the fire. Presently Ethel and the Sq [?] came in and the conversation took [?]

[?]her turn. Soon after. Virginia, plea [?] [fati?]gue, went to her room. "Well," she thought undressing [mech?]anically, "my dream is ended. I was right, and he has been simply am[?] himself with me. What is it that m[?] me love him still now that I see so cl[?] that every tender word and look and [?] were so many lies? What right had I {?] gratify his contemptible vanity at the [?] pense of so much suffering? What a bl[?] blind fool I have been to imagine fo[?] moment that a man like him could [?] anything to like in me! I used to th [?] he was a gentleman. Would a true g [?] tleman take advantage of a woman's ig[?] rance and confidence and amuse himself [?] at her bitter cost? No!" Then the b[?] blood inherited from her mother asserti[?] itself, she exclaimed, "if he is not a g[?] tleman he is not my equal, for I am a lad[y?] I would scorn to take a mean advantag[e?] of any one. Then, if he is my inferior [?] will not love him, for I cannot love a [?] on whom I look down" Saying this she slipped on her ni[ght?] dress, and, standing before the old-[?] ioned glass, began to unbraid the [?] thick tresses of her hair. The dim [?] of her bed-room candle flared down her, she looking steadily the while own reflection. She noticed how wa[?] thin her face was, surrounded by this flowing, dark hair --how sunken he[?] were with the dark rings under them. "And this," she thought, "is the res[t?] of his work. This is what comes of ha[?] ing the monotony broken up. This is what comes of putting faith in the honor of a man of the world." "She leaned her arms on the bureau, and gazed steadily into her own eyes for a long time. "We'll have to go go to the wedding, of course. I might get rid of it by going down to aunt Mary's, but I won't be a [c?]oward."

Under cut right side:

[?]7th of [?]option [?] place [?]eene, [?]lepar[?] now [?]tony. [?]ward [?]pense [?]now, [?]the re [?] their

[?] look[?]t was [?]s on [?]ecall[?] bud[?]at the [?]reen. [?]would [?] dura[?]ields. [?]gnor[?] her [?]nd of [?] fixed [?]gie?" [?]. "I [?] that [?]d try [?] wish [?]I cut [?] day. [?]hat I [?] will [?] than [?]s dis[?]don't [?] good [?] after [?]d, the [?]a seedy, toothless, disagreeable old man before long. Come Virginia, are you going to try my hair?" "I don't know how, Nellie; I didn't see her hair" "No, I suppose not. You were probably admiring Sir Edward's, or straying off, in your speculative way, a quarter of a century or so into the future." "Don't Nellie," said Virginia, irritably. "Well, you're cross enough." "Am I? I don't feel cross, Nellie, but I'm tired, and don't want to talk."

ksul-uasc-mscc208_014

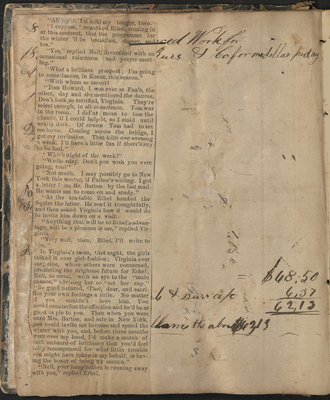

"All right. I'll hold my tongue, then. " "I suppose," remarked Ethel, coming in at this moment, that the programme for the winter 'll be breakfast, dinner and tea." "Yes," replied Nell, diversified with an occasional rainstorm and prayer-meeting." "What a brilliant prospect; I'm going to some dances, in Keene, this season." "With whom as escort?" "Tom Howard. I was over at Fan's, the other, day and she mentioned the dances. Don't look so terrified, Virginia. They're select enough, in all conscience. Tom was in the room. I did'nt mean to the lose the chance, if I could help it, so I staid until nearly dark. Of course Tom has to see me home. Coming across the bridge, I got my invitation. That kills one evening a week. I'll have a little fun it there's any to be had." 'Which night of the week?" "Wednesday. Don't you wish you were going, too?" "Not much. I may possible go to New York this winter, if Father's willing. I got a letter from Mr. Barton by the last mail. He wants me to come on and study." "At the tea-table Ethel handed the Squire the letter. He read it thoughtfully, ans then asked Virginia how it would do to invite him down on a visit. "Anything that will be to Ethel's advantage, will be a pleasure to me." replied Virginia. "Very well, then, Ethel, I'll write to him." In Virginia's room, that night, the girls talked it over girl-fashion: Virginia ever sanguine, where others were concerned, predicting the brightest future for Ethel; Nell, as usual, with an eye to the "main chance", advising her to "set her cap." "Be good natured,'Thel, dear and sacrifice your own feelings a little. No matter is you couldn't love him. You could counterfeit affection and he'd be as good as pit to you. Then when you were once Mrs. Barton, and safe in New York, you could invite me to come and spend the winter with you, and, before three months were over my head, I's make a match of such unheard-of brilliancy that you'd feel fully recompensed for what little trouble you might have taken in my behalf, in having the honor of being MY SISTER." " Nell, your imagination is running away with you, " replied Ethel.

ksul-uasc-mscc208_015

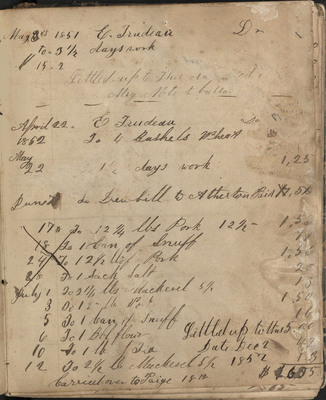

May 3 1854 E. Trudeau Dr to " 3 1/2 days work 15.2

Settled up to this day [?] My Note to balance

April 22 E Trudeau 1852 To 4 Bushels Wheat [?] May 22 1 1/2 days work 1.25

June 7 Dewbill to Atherton Paid x7.5x0 X 17th to 12 1/4 lbs pork 12 1/2- 1.53 18 to 1 can os snuff 11 24 to 12 1/2 lb of pork 1.56 28 to 1 sack salt 20 July 1 to 2 1/4 lbs mackerel 5 1/2 13 3 to 12lbs pork 1.50 5 to 1 can of snuff 1.6 6 to 1 bbl flour 5.00 settled up to this date dec 2 1852 10 to 1 lb of tea 4.2 12 to 2 1/2 lbs mackerel 5 1/2 1.3

Carried over to Page 18th $16.05

ksul-uasc-mscc208_016

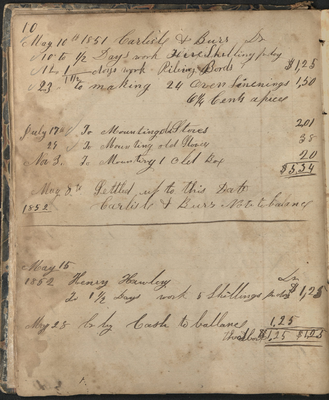

10 May 10th 1851 Carlise & Burr Dr 10 to 1/2 days work hire shilling per day 12 1 days work piling bords $1.25 23 1 1/2 to making 24 oven linenings 1.50 61/4 cents a piece

July 17th to mounting old stoves 2.01 29 to mounting old stoves 38 Nov 3. to mounting 1 old box 20 $5.54 May 8th Settled up to this Date 1852 Carlisle & Burr Note to balance

May 15 1852 Henry Hawley Dr To 1 /12 days work 5 shillings per day $1.25 May 28 Cr by Cash to balance 1.25 [thead Corp] $1.25 $1.25

ksul-uasc-mscc208_017

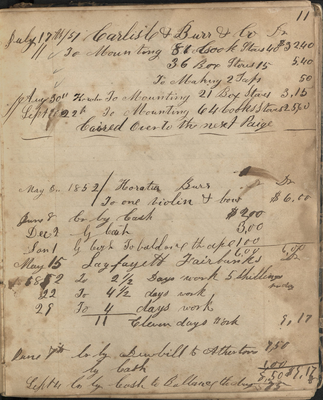

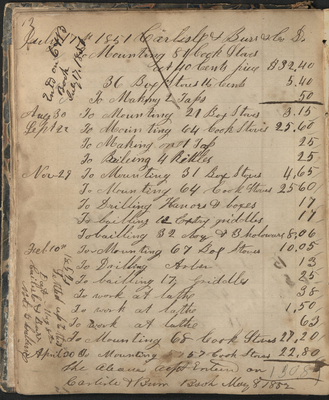

11 July 17th/51 Carlisle & Burr & Co [Dr?] //To Mounting 81 Cook Stoves 40 $32.40 36 Box Stoves 15 5.40 To Making 2 Taps 50 //Aug 30th Horatio To Mounting 21 Box Stoves 3.15 Sept 22nd To Mounting 64 Cooks Stoves 25.60 Carried over to the next page

May 3.. 1852 / Horatio Burr [Dr?] To one violin & bow $6.00 June 8 Cr by Cash $2.00 Dec 2 by Cash Jan 1 by Cash To [bald one the ape] 1.00 6.00 6.00 May 15 Layfayett Fiarbanks [Dr?] 1852 To 2 1/2 Days work 5 Shillings per day 22 To 4 1/2 days work 29 To 4 days work 11 Eleven days work 9.17 June 7th Cr by Dewbill t0 Athertons 7.50 by Cash 1.00 8.50 $9.17 Sept 4 Cr by Cash to Balance the day 8.75

ksul-uasc-mscc208_018

12 July 11th 1851 Carlisle & Burr Co Dr (X marked through first 5 lines) Entered on 6 & 13 Book July 17, 1851 (sideways on page) To Mounting 81 Cook Stoves At 40 cents piece $32.40 36 Box stoves 15 cents 5.40 To Making 2 Taps .50 Aug 30 To Mounting 21 Box Stoves 3.15 Sept 22 To Mounting 64 Cook Stoves 25.60 To Making one tap .25 To Bailing 4 kettles .25 Nov 29 To Mounting 31 Box Stoves 4.65 To Mounting 64 Cook Stoves 25.60 To Drilling [Hanors] & boxes .17 To bailing 12 [extry] griddles .17 To bailing 32 [Noy?] & Bholoware 8.06 Feb 10th To Mounting 67 Box Stoves 10.05 To Drilling [Auber?] .13 To bailing 17 griddles .25 To work at lathe .38 To work at lathe 1.50 To work at lathe .63 to Mounting 68 Cook Stoves 27.20 To Mounting 57 Cook Stoves 22.80 The [Al?] [eft] [enter] on 13.84 (in pencil) Carlisle & Burr Book May 8 1852 (in side margin) Settled up to this Date May 8th Carlisle Y Barr Note to balance